Auspicious Sight: The Halqeh-e Nur Spectacles

Extraordinary diamonds make for extraordinary tales. The Halqeh-e Nur Diamonds offer a glimpse into Mughal decadence like none other.

A history that dazzles

Natural diamonds have extraordinary tales to tell as they pass from one owner to another across oceans and continents down the centuries. Formed deep in the earth’s mantle billions of years ago, natural diamonds are prised out of their secret hiding places by inquisitive human hands. Stones with a genesis too old to remember were perhaps the gifts of gods, but all precious diamonds somehow become entwined in human dramas of love and loss, daring and intrigue, power and politics.

Natural diamonds have borne material traces of their social history ever since they were first polished. In India, the source of almost all the world’s oldest diamonds, religious and royal patrons valued size and purity over brilliance of cut. But from the sixteenth century, European lapidists developed complex geometric cuts, which meant even though diamonds lost carats, they gained fire to their sparkle. Many exceptional old Indian diamonds were dramatically recut at different points in their journey.

The Eyes of the Beholder

Some natural diamonds, however, preserve their older shapes against the vicissitudes of fashion, especially if they are not suitable for recutting. In October 2021, Sotheby’s offered a unique pair of diamond spectacles for sale in London, known as the Halqeh-e Nur or “Halo of Light,” made in Mughal India in the seventeenth century.

The lenses are sensational flat cut natural diamonds with skilfully faceted edges that maintain the transparency of the lens but also reflect light. They are cleaved from a single Golconda diamond believed to have been about 200 carats in size. The lenses themselves have a joint weight of about 25 carats. Unusually for diamonds cut in India, the wastage was huge, but the flawless quality of the raw diamond must have inspired the decision to create these unmatched lenses.

Technical analysis indicates they are the work of skilled lapidaries at the imperial Mughal court probably made in the period of Shah Jahan. Each slice of natural diamond is incredibly pure and very thin at just 1.6 mm in depth. Generally speaking, we look into natural diamonds to marvel at their clarity and the dazzling way they absorb, refract and reflect light. In this case, however, the purpose was to be able to look through the diamond. The glitzy setting of the lenses dates from the late nineteenth century, but the diamond lenses may originally have been hand-held pince-nez spectacles, which can be seen in some Mughal paintings of the late sixteenth century.

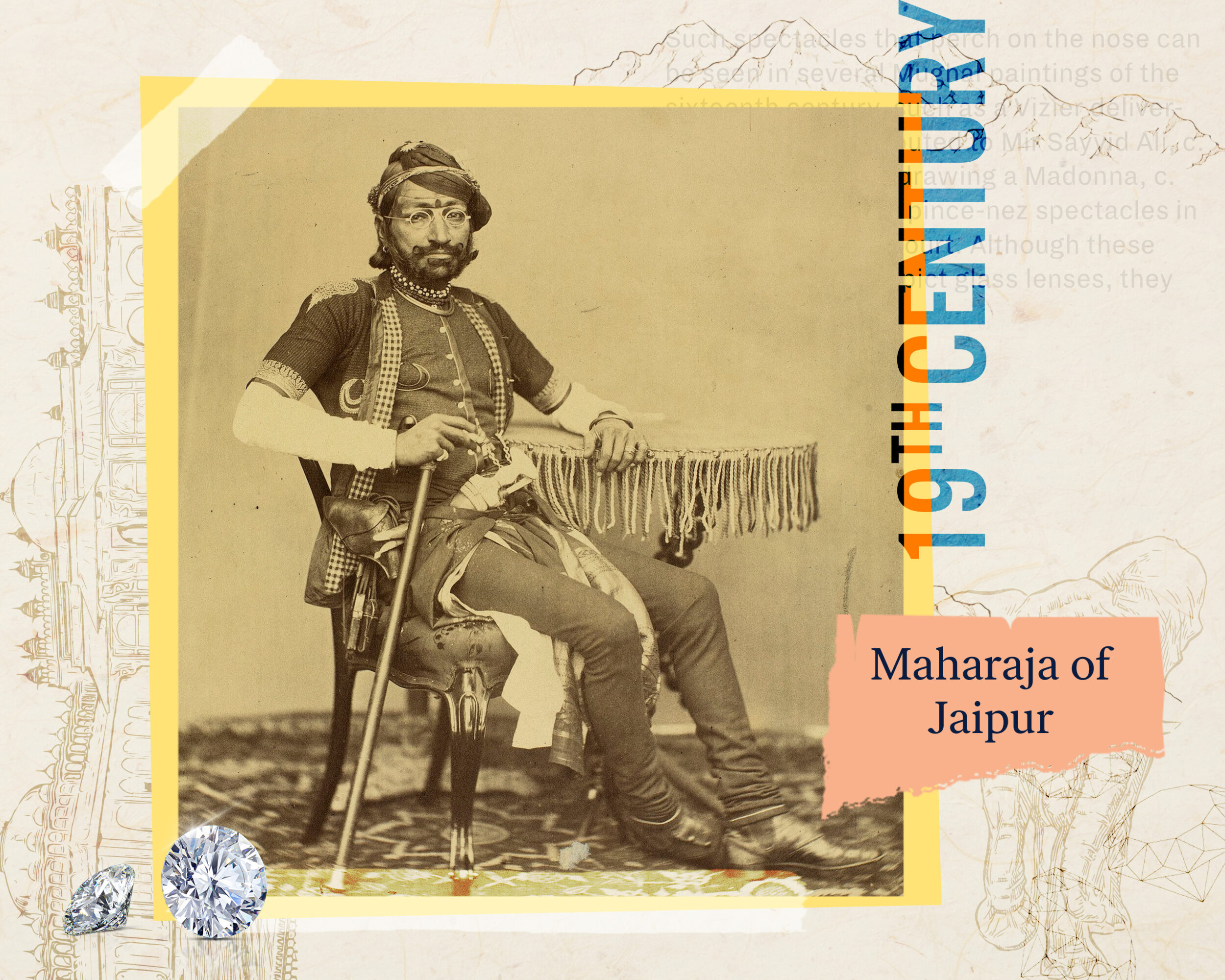

Such spectacles that perch on the nose can be seen in several Mughal paintings of the sixteenth century, such as a Vizier delivering a Petition, attributed to Mir Sayyid Ali, c. 1556, and an artist drawing a Madonna, c. 1580-90 both show pince-nez spectacles in use at the Mughal court. Although these almost certainly depict glass lenses, they offer a context for our understanding of the reception and use of spectacles at the Mughal court.

Sacred Insight and Mughal Kingship

A natural diamond of this importance would almost certainly have belonged to the Mughal emperor. So, what did these diamond lenses mean to their first wearer? Their purpose was not to correct vision but to convey opulent and symbolic meanings about sacred insight and kingship. The Mughals were preoccupied with light imagery to express their dynastic rule. They drew on mystic Sufism, as well as Zoroastrianism and Hinduism, to convey the idea that the emperor was a ray of divine light (farr-i izadi). They believed a ruler imbued with cosmic light would rule justly and benevolently. The diamond spectacles thus symbolised divine wisdom and gave auspicious sight to the wearer, something of great importance in a court culture that valued astrology, omens and auguries.

Perhaps the lenses also reminded Mughal audiences of the long and revered traditions of scientific enquiry relating to vision in India and the Islamic world.

But how did the lenses get from the Mughal court to the present day? Very little information is in the public domain about their ownership past or present. It seems they were preserved in the treasury of a great princely family of India for several centuries. Sometime in the mid twentieth century, they changed hands and were brought out of India, at a time when many disposable assets were moved overseas. Since then, they have apparently spent most of their life in a bank vault in Zürich, apart from being occasionally exhibited and having a glamorous world tour prior to the Sotheby’s sale in 2021.

Without knowing any precise details of their provenance, we can still deduce much about the journey of these diamond lenses on account of their eye-catching frames, with rose cut diamonds set in the pachchikam technique. This method involves setting the stones directly into gold or silver (like the Indian kundan technique favoured by the Mughals) but also employs a European ‘open claw’ design to support the diamonds. It was favoured towards the end of the nineteenth century, giving the frames a date around 1890.

Legacy of a Unique Journey

The use of the pachchikam technique tells us the spectacles were still in India at the end of the nineteenth century. They clearly belonged to a family with opportunities to wear such statement accessories and who found the 1890s an expedient moment to update them. The choice of frames is unmistakably Indian, but also has a nod to European taste and aesthetics. This all fits perfectly with the profile of India’s Nawabs and Maharajas under the British, who adopted many strategies of conspicuous display in order to maintain their political position. The spectacles surely dazzled colonial overlords with their wealth, while also asserting dynastic legitimacy to their subjects.

The late nineteenth-century owner also clearly had an interest in Indian numerology. Each of the lenses is surrounded by seventeen natural diamonds; the bridge has thirteen; and each of the arms has one larger diamond at the hinge. These are all prime numbers expressive of the uniqueness of the spectacles. Seventeen is a number associated with dharma (1) and with esoteric insight (7), while the number thirteen in India is considered lucky, expressing completeness and attainment. It thus seems that the frames reassert the seventeenth-century notion of auspicious sight more than two hundred years after they were first made.

These diamond lenses are a virtuoso masterpiece. To make them required extraordinary wastage of a huge diamond and we have already noted this was unusual for the Mughals. Could it possibly be that the rest of the diamond is hiding in plain sight? Could the diamonds in the frames be cut from the remainder of the diamond? They are the same type of Golconda diamonds, but without prising them from their settings, we can only speculate. Even then it might be impossible to prove.

The diamond spectacles unfortunately did not sell at Sotheby’s on 27 October 2021. Like the rest of our covid-struck world, they must wait for a more auspicious and certain day. But they were universally loved on their world tour, capturing the attention of the press wherever they went. That’s why in my view they are perfect for a museum, where children and adults alike can let their historical imagination run free about the journey of such a unique and incredible natural diamond.