Discovering the Rich Heritage of South Indian Temple Jewellery

The art and history of temple jewellery continue to inspire natural diamond-studded designs across South India even today

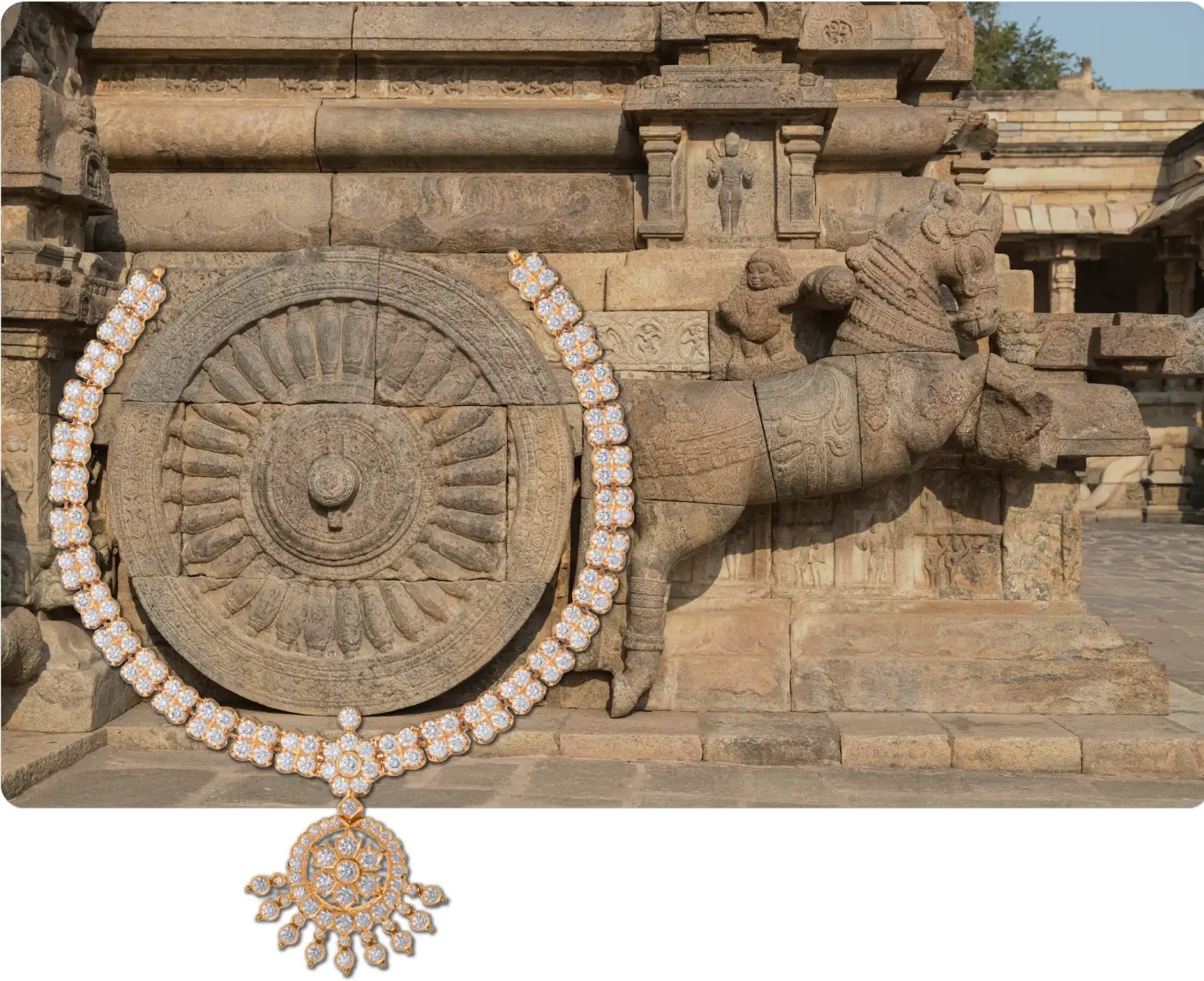

Kishandas & Co crafts dazzling bottu malai - a necklace composed of linked coin-shaped elements set with gems - exclusively in fine natural diamonds. Image credit: Adobe Stock, Unsplash • Jewellery: Kishandas & Co

In the year 1010, Queen Kundavai, the sister of Rajaraja, the greatest among the mighty Chola dynasty that ruled much of South India between the 10th and 13th centuries, donated a sacred gold girdle to adorn the hips of Lord Brihadeshwara, at the eponymous temple in Thanjavur. In addition to a massive number of rubies and pearls, the girdle was encrusted with “ six hundred and sixty-seven large and small diamonds with smooth edges set into it…” describes one of the many inscriptions that line the walls of the thousand-year-old temple, built by Rajaraja himself.

The journey of these dazzling divine jewels from the gods to the people who worshipped them is a story of kings, dancers, faith and master craftsmanship.

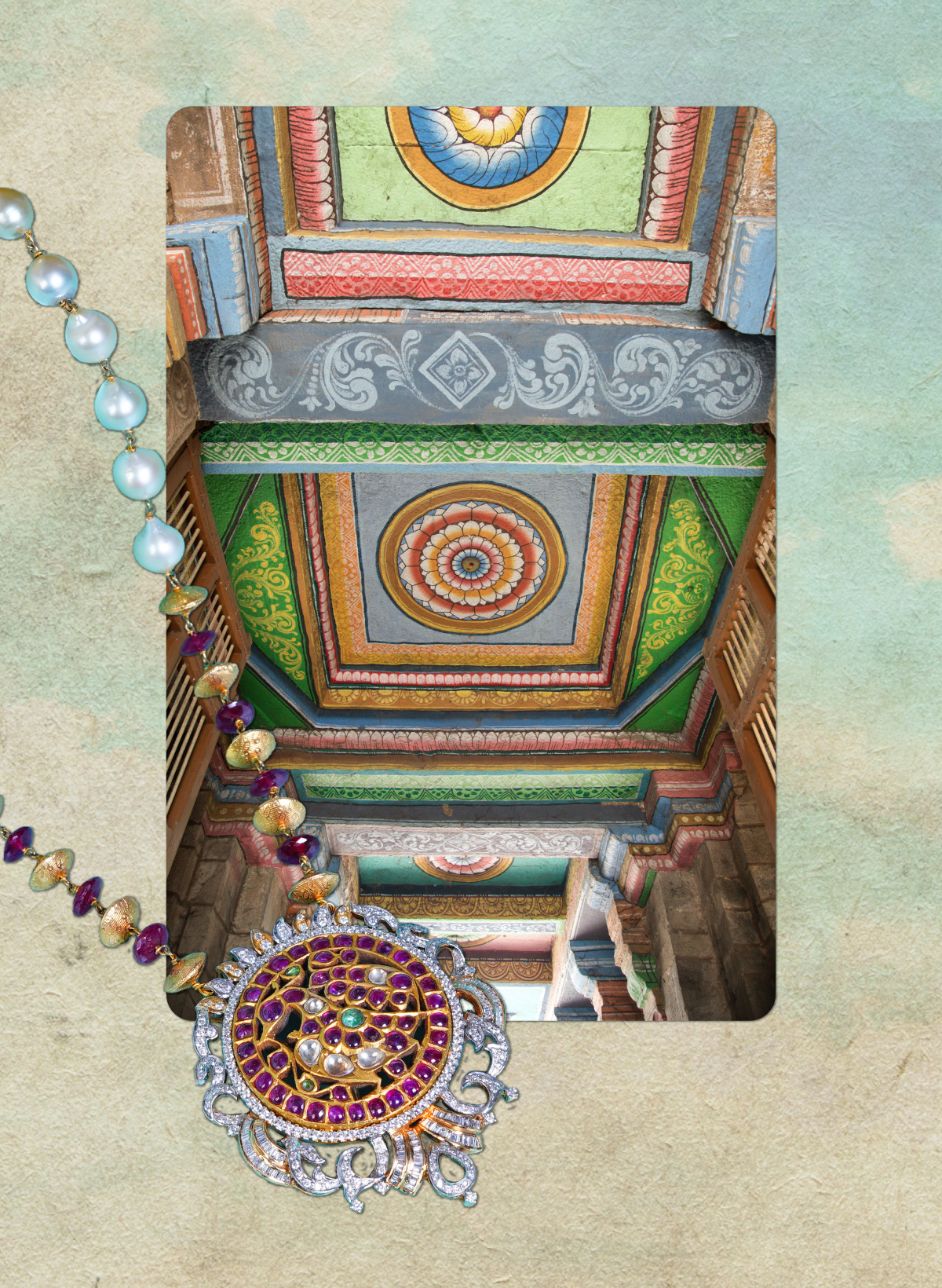

Kishandas & Co reimagines temple-style jewelry traditionally encrusted with gems like rubies,

emeralds and sapphires, entirely in diamonds. • Image credits –Kishandas & Co, Adobe Stock

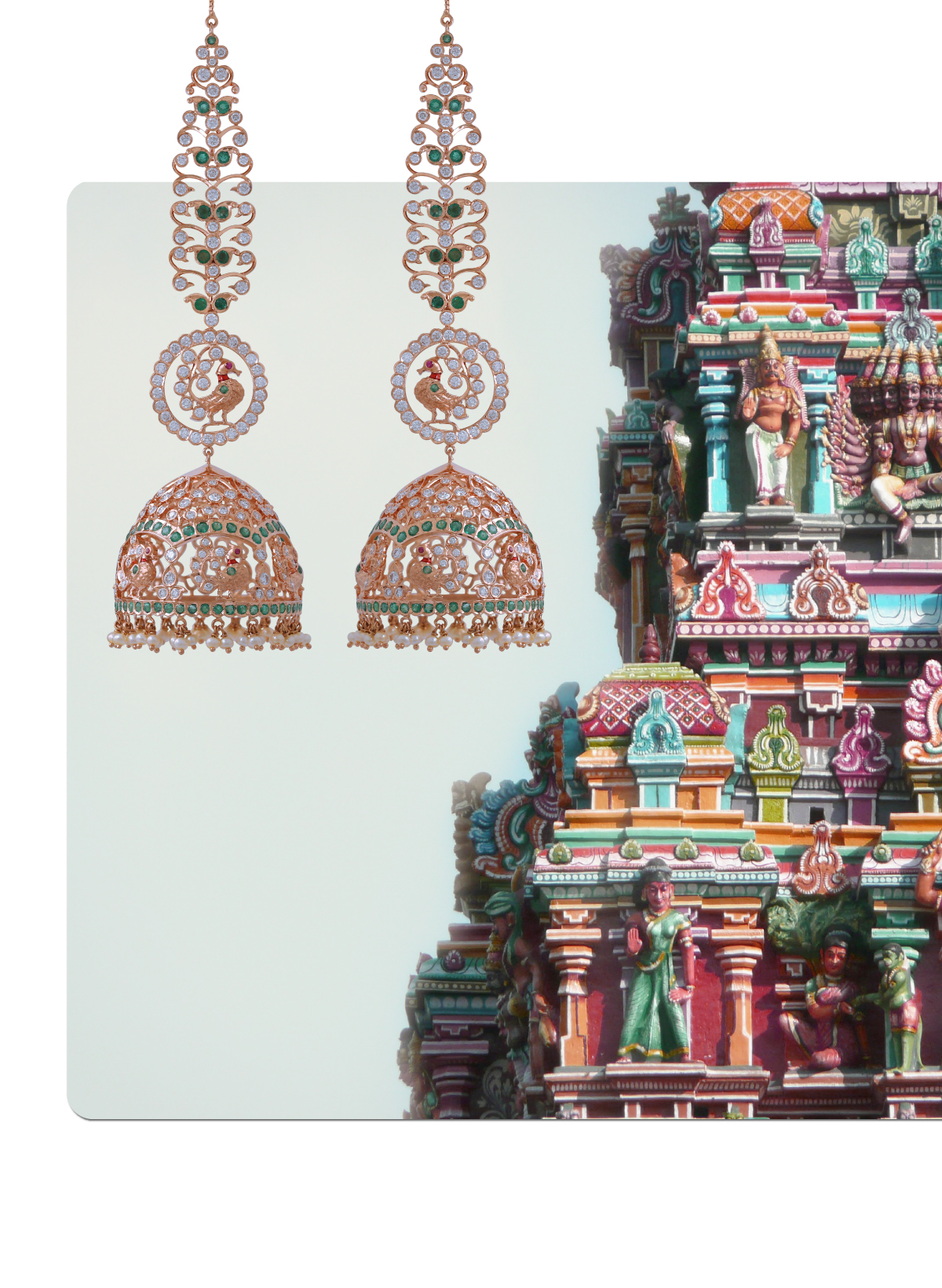

The Glittering Jewels of Chola Temples

During the Chola reign, “The enormous booty from the coffers of the Cheras, Pandyas, Lanka and Chalukyas was turned into ornaments for the temple deities,” writes Raghavan Srinivasan in his book, Rajaraja Chola: Interplay Between an Imperial Regime and Productive Forces of Society. The rich tapestry of southern India’s fabled temple jewellery is rooted in this royal tradition of adorning deities with exquisite jewellery. “Originally, the jewellery of the temple deities were entirely made of precious stones set in metal—not only gold, but also silver and brass,” says N Anandha Ramanujam of NAC Jewellers. “The patterns usually floriated vines, peacocks and hamsa (swans) and mango, and metal formed the framework for the precious gems. That ancient technique is now lost, ” he added, “The gold-heavy sculptural jewellery we see today began to be crafted later.” These dynasties were also great patrons of dance and music that was performed in the temples they built. The temple dancers were the first to begin wearing replicas of the jewellery originally worn by the deities, and soon the styles penetrated to the general populace and became a distinct and popular form of jewellery preferred by people across the region.

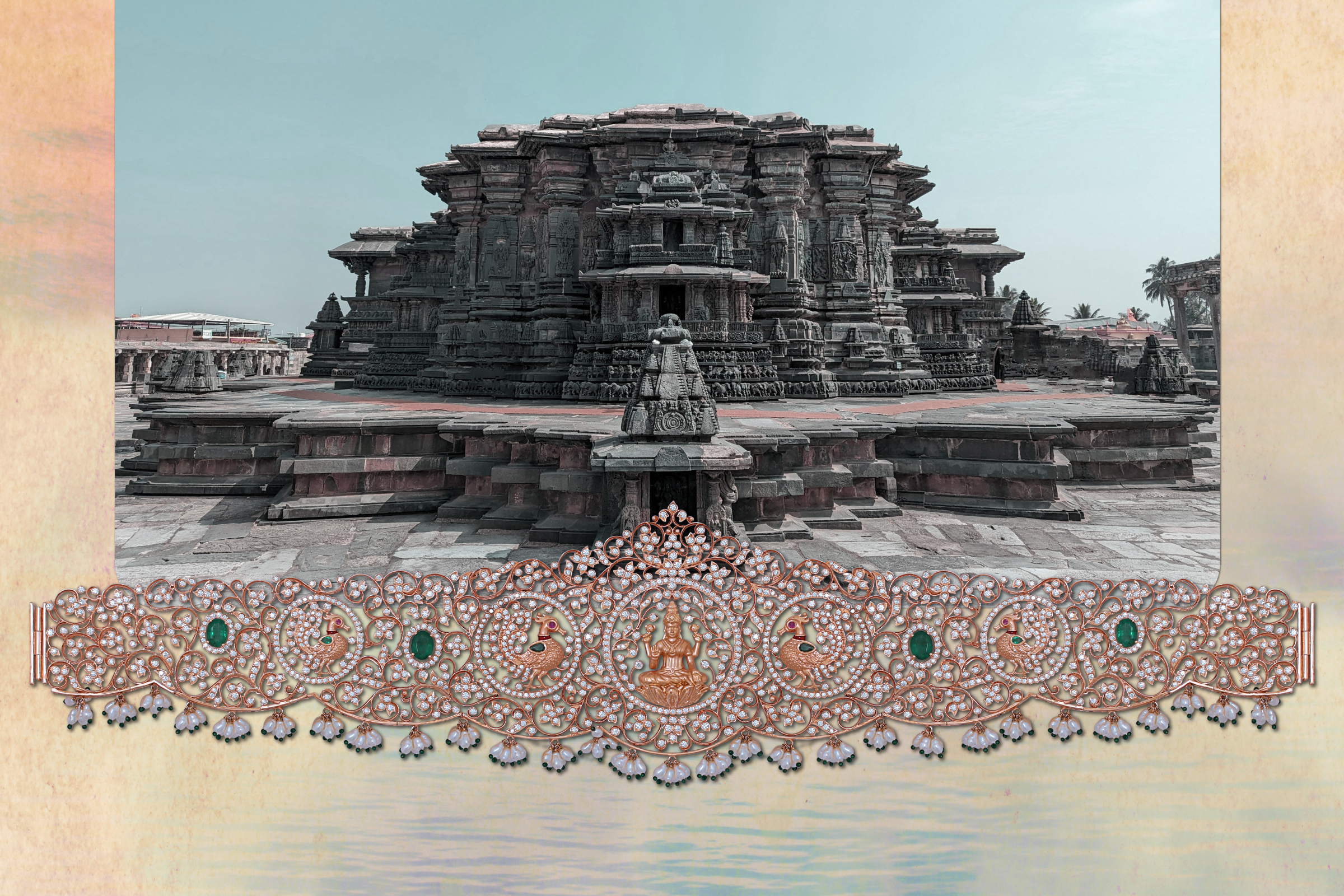

Baroque extravagance meets contemporary aesthetics in this elaborate necklace crafted in intricate floriated patterns

interspersed with depictions of the mythical annapakshi bird and the Hindu goddess of wealth, Lakshmi

Over time temple jewellery evolved into a spectacular medium of story-telling, as master craftsmen worked sheet gold in the repousse technique to illustrate entire mythological tales and legends in intricate sculptural forms inspired by temple architecture, encrusted with dazzling gems in brilliant colours. The deities who once wore exquisite jewellery turned into motifs that embellish them

“While there’s a dearth of visual documentation from Chola age, we see a preponderance of sapphires, rubies and emeralds in the jewellery of the age, Diamonds were rare and special, used only by royalty or in their offerings to their deities.” says Pratiksha Prashant of jewellery house Kishandas & Co that designed the jewellery for Mani Ratinam’s magnum opus Ponniyin Selvan set in the 10th century against the backdrop of the rule of the Chola Dynasty. “Until the 18th century, India was the sole producer of diamonds and the best diamonds in the world came from the Golconda region. In our culture, the best is offered to the Gods. So, the dazzling diamonds from the region, particularly special due to their zero-hydrogen properties, were used primarily in temple jewellery,” explains Amarendran Vummidi of the century-old Vummidi Bangaru Jewellers in Chennai.

The Chettiar Gems

Many of these gems that adorned the deities of the Cholas perhaps came through the hands of the Chettiars, a rich mercantile class originally from the ancient port of Puhar, who emerged as influential gem dealers, ship chandlers, and salt merchants in the Chola Empire. After the fall of the Cholas in the 13th century, the Chettiars settled in about seventy-five villages around a single temple near present-day Karaikudi in south-central India, (then part of Pandya kingdom).

Some of the most exquisite specimens of temple jewellery are found in the Chettinad region of Tamil Nadu, home to the Chettiars. Prolific traders, the Chettiars had trade links with numerous countries including Ceylon, Malaya and Burma. The Chettiar traders brought back Burmese rubies and spinels from the Mogok mines in Burma. So rubies were prolifically used in the opulent jewellery of the prosperous Chettiar community. Over time, as natural diamonds became more available, they became entrenched in the tapestry of Chettinad jewellery.

A particularly iconic piece of jewellery worn and cherished by men of the Nattukottai Chettiar community and Shaivite priests of the Chidambaram temple is the Gowrishankara. This piece of jewellery is akin to a portable shrine, with the lingam box containing a sacred object called the jangam (mobile) lingam, suspended from the massive pendant embossed with intricate sculptural forms, typically Shiva mounted on his vaahan the bull, Nandi, or in the form of Nataraja. A nineteenth-century specimen exhibited at the Musee Barbier-Mueller Museum in Geneva, features the deity Kartikeya (son of Shiva), seated on his vahan, the peacock, flanked by his consorts and rearing lions. The lingam box is adorned by two large rubies that flank a large table-cut diamond.

Another iconic piece of jewellery from the region is the Makari malai necklace, traditionally worn by men on their wedding day. A particularly stunning late 19th century piece from the Chettinad region now housed in a private collection, is archived in the book Indian Jewellery: Dance of the Peacock by historian Usha Balakrishnan. “This necklace with diamonds, cabochon rubies and emeralds closed-set in gold has no less than 536 diamonds,” she writes. The manga malai—composed of linkedmango-shaped elements in gold set with gems—is another popular style of temple jewellery. Sotheby’s in London houses an exquisite 19th-century mango malai, from Tamil Nadu, made in gold set with rubies, diamonds and emeralds using the kundala-velai technique and estimated at a whopping 50,000 – 70,000 GBP.

The influence of the Nattukottai Chettiars and their temple-building feats were not restricted to the subcontinent. They also set up temples across Southeast Asia as they travelled through and settled across the region, establishing business ties. Among the artefacts displayed by the India Heritage Centre in Singapore when they opened doors were exquisite pieces of Chettiar temple jewellery studded with diamonds and other gems from 20th century Vietnam, loaned by Saigon Chettiars Temple Trust.

“A grand jewellery piece of the Chettiar community is called Kalathhi which is presented to the bride during wedding ceremonies, and typically passed down through generations, is almost entirely made with diamonds,” says Vummidi.

Vummidi Bangaru Jewellers’s exquisite necklace comprising curve-edge 3d diamond-shaped segments adorned with annapakshi bird motifs is evocative of temple-style necklaces like the manga malai and bottu malai.

Natural Diamond Temple Jewellery in the 21st Century

Jewellers like VBJ and Kishandasuse fine natural diamonds to script a new vocabulary for age-old temple jewellery. At Kishandas for instance, dazzling bottu malais are crafted entirely out of fine natural diamonds. “The adigai, that traditionally featured a single string of rubies, are made out of fine diamonds instead of rubies, using the close-setting technique,” says Pratiksha. VBJ, on the other hand, not only crafts Temple jewellery for mortals, they also craft jewellery for the divine. “We create a lot of jewellery that adorn deities in many temples. We have also crafted the decorative arches – Prabhavali, placed around the icons in many South India temples, in gold, encrusted with diamonds.” says Vummidi Among VBJ’s most iconic creations is a platinum sacred thread complete with a stunning Brahmamudi or knot, made of 30 carats of diamonds, for Balaji in Tirupati.

A year ago VBJ also launched the Annapakshi collection—centered around the eponymous celestial bird, a recurring motif in temple architecture across South India, in its design. From a bridal set priced at Rs 3 crores to smaller pieces like earrings and pendants, the collection dazzles with its intricate and opulent use of natural diamonds, with a smattering of other gems. Some of the pieces combine dainty floriated patterns with sculptural depictions of Lakshmi or the Annapakshi birds. Each piece is a spectacle.

If VBJ is creating contemporary renditions of traditional temple jewellery, NAC is using antique pieces of temple jewellery to craft new pieces that combine the old with the new, quite literally. “For instance, we have a huge collection of rakodis (hair ornaments) from Chettinad and other regions of South India, like Thanjavur, that are no longer used in their traditional manner. We are using these as pendants instead in our temple-style necklaces,” says Ramanujam. While some of these antique pieces come studded with uncut diamonds along with rubies and emeralds, in some pieces these rakodis come framed with diamond-studded floriated vines.

Studded with pieces of the past, each piece has a story of its own and a new generation of people who are opting for this wearable divinity.