Natural Diamonds: A Global Phenomenon that Spans Centuries

No precious stone has captured the minds of people the world over the way Natural Diamonds have. With their history rooted in India, diamonds travelled all around the globe over the centuries as trade flourished, and artefacts, ideas, and skills were exchanged across cultures.

Indian natural diamonds have been renowned around the world for their extraordinary beauty and size for thousands of years. Until the 17th century, the Golconda mines in the Godavari Delta—a region in today’s Andhra Pradesh and Telangana—had been the only source of diamonds in the world. Legends of the marvellous Golconda gems are present in sources from around the world: Ancient Greece, the Tang (618-907 CE) and Song (960-1279 CE) Dynasties in China, and the Middle-East. In the 13th century, the Venetian traveller Marco Polo narrated how diamonds could only be found and collected in the Kingdom of Motupalli (today’s Machilipatnam). Although he never actually travelled to those regions and relied on hearsay, Polo’s stories confirm the longstanding human fascination for diamonds and the mythical status that Indian gems had.

Illustration: Squadron 14; Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

These legends show that the knowledge and interest in natural diamonds had reached every corner of the known world way before our times. More interestingly though, it hints at the fact that a global market for diamonds has existed for centuries. From the beginning, India played a central role in the diamond industry as it was the first place where these gems were mined, sold, and worn. On the international market, Indian diamonds were paid for by European merchants with African and Peruvian emeralds, Mediterranean coral, as well as gold and silver. Venice, one of the major exchange cities for Middle Eastern and Asian goods in Europe, became the trading and processing centre for diamonds in the fifteenth century.

Rise Of Europe

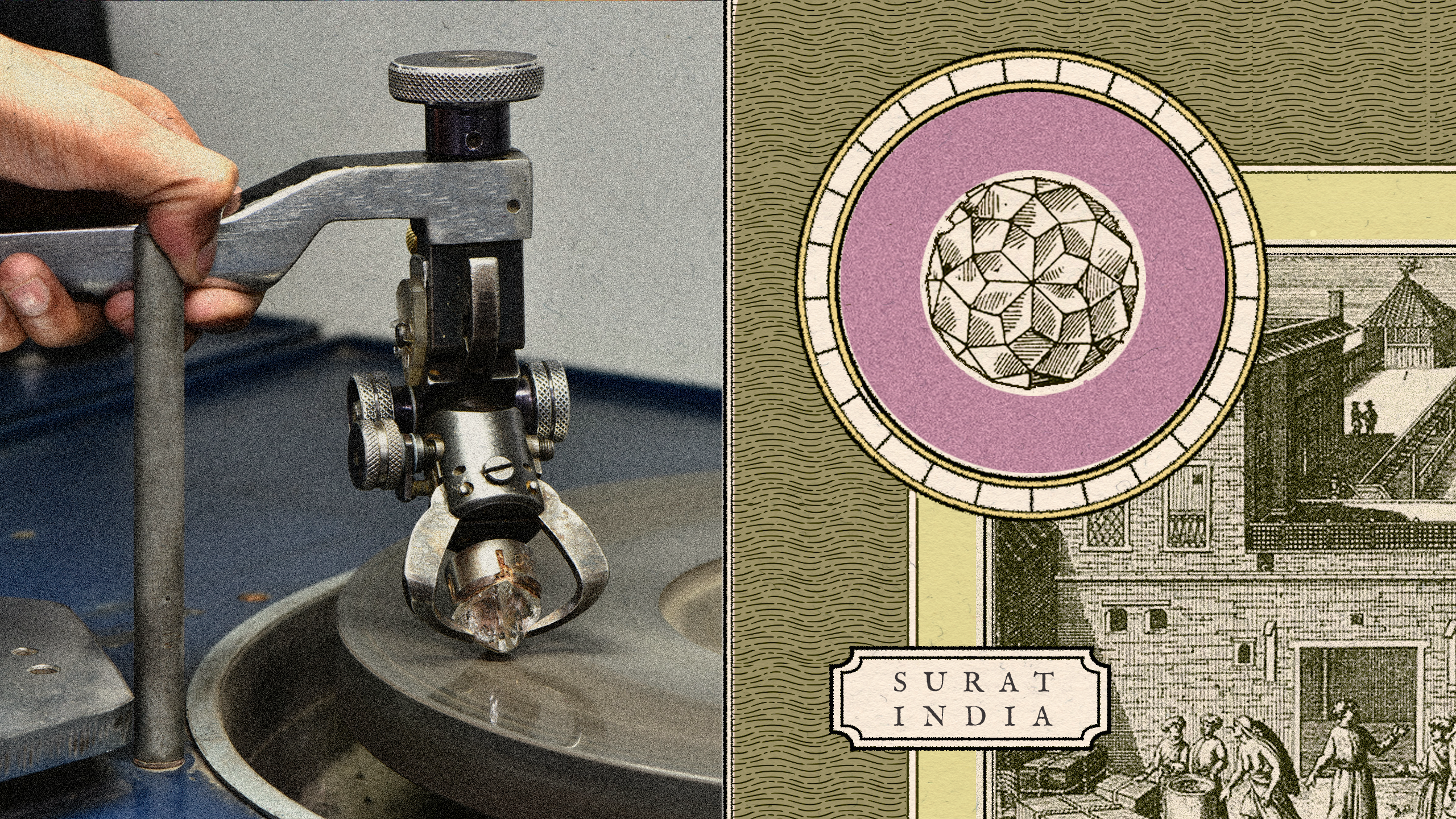

In ancient times, uncut diamonds were common because the tools to overcome the hardiness of the stones hadn’t been invented yet. The natural diamonds found in early jewellery were uncut and therefore remained in their natural octahedron shape. In the fourteenth century, diamond powder began to be used to polish gemstones and a new shape, the table cut, became popular. The top point of the gem was flattened in order to create a flat, light-reflecting facet. The result was that diamonds acquired a more definite shape and more brilliancy. Although the original polishing techniques had been developed in India, it was in Europe that new cuts and shapes made diamonds (literally) shine. Between the late sixteenth and seventeenth century, the invention of a spinning wheel known as scaife allowed the creation of facets on a gem. New cuts, such as the rose and the brilliant cut, brought more variety to the market and new found knowledge of the light-refracting potential of diamonds. In the second half of the 1600s, the Venetian diamond cutter Vincenzo Peruzzi created the first 58-facet cut. With the discovery of the Americas and new maritime routes to India, Venice lost its monopoly with the East and Antwerp rose to prominence in the 1500s.

Illustration: Squadron 14; Color Image Left: Wikimedia Commons

Because of its strategic geographical position, the Belgian city Antwerp has been one of the major diamond trading centres in the world for more than 500 years. The first evidence of diamond trade appears in a 1447 edict against the trade of “any false stone imitating diamonds, rubies, emeralds and sapphires…” Essential for the city’s role as the international trading hub was the Jewish community. Famous for their knowledge in polishing techniques, the Jews could rely on their community connections which ensured a trusted system for buying and selling diamonds. Although the importance of Antwerp as a trading centre has fluctuated along the centuries, around 84% of rough diamonds and 50% of cut diamonds in the world are still traded in the city.

.Illustration: Squadron 14; Bottom colored image: Wikimedia Commons

The Jewish Connection

The fate of the Jewish community and diamonds did not stop in Antwerp. When Belgium was occupied by the German forces during WWII, many of the Jews connected to the diamond trade were captured and killed. The survivors fled to New York and Tel Aviv where they established new diamond centres. Today, Israel is an important hub for the trade and manufacturing of polished diamonds and is responsible for groundbreaking technological advancements such as the laser for cutting and the automation of bruting and polishing.

While these refinements were appreciated across the European market, the Indian one favoured carats over brilliancy. Through polishing and cutting, a diamond would increase its refractory abilities but reduce its weight by sometimes as much as or more than 50%. As the Indian market priced its diamonds by weight, cutting would cause a loss of profit. This preference also explains why famous diamonds went through the cutting process only after reaching Europe. For instance, when the Koh-i-Noor was acquired by Queen Victoria (1819-1901), it went through a cutting process that reduced its weight from the original 191 carats to 105.6. Before it was cut, the Koh-i-Noor had been displayed at the Great Exposition in London in 1851. The British newspaper The Times reported the shock of the public in seeing such a simple gem: “Many people find a difficulty in bringing themselves to believe, from its external appearance, that it is anything but a piece of common glass.”

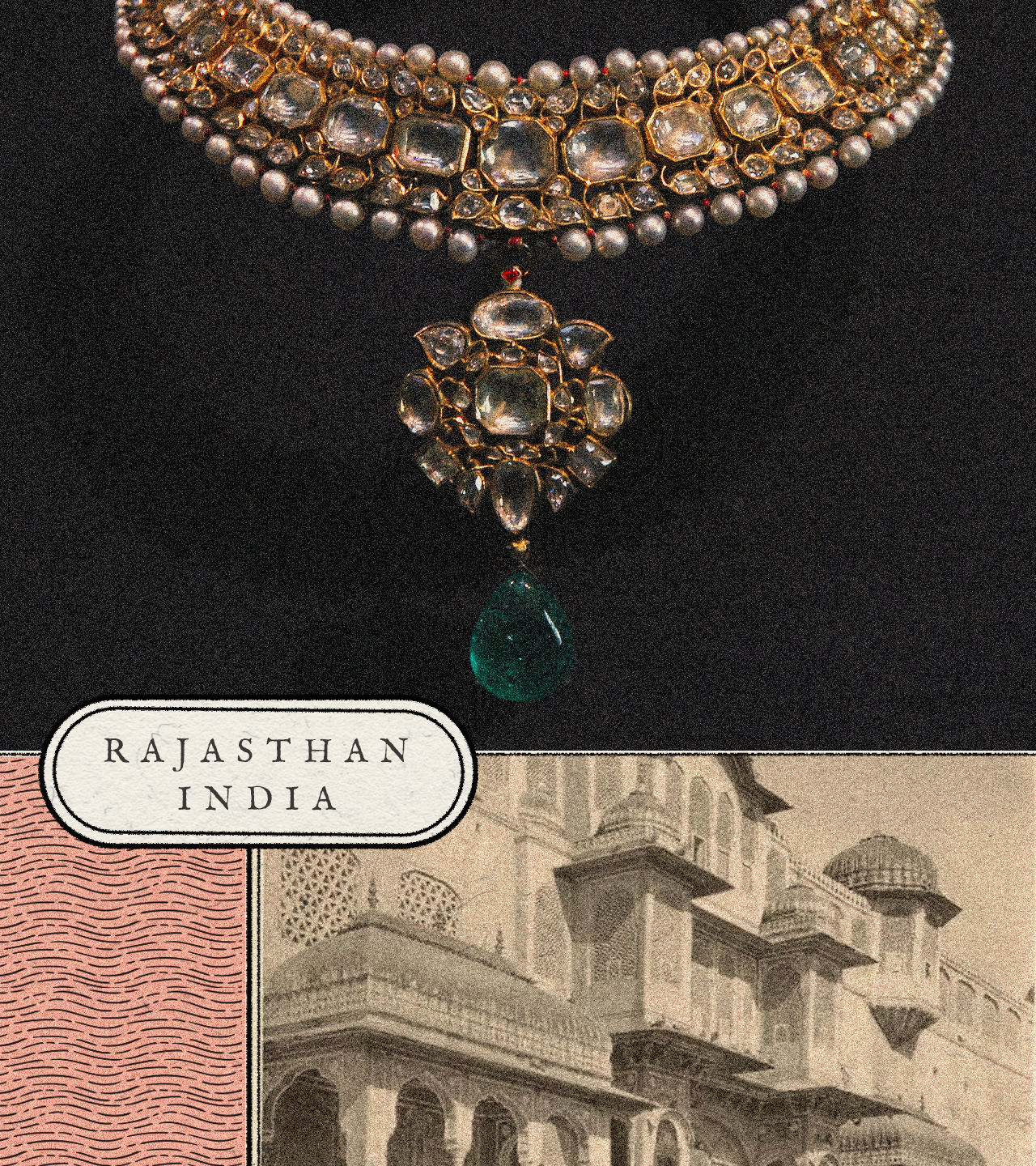

Natural Diamond Craftsmanship In India

The diamond trade not only contributed to a consistent flow of precious goods from South America and Africa through Europe and to Asia, but also to an exchange of knowledge, skills, and techniques. The varied geographical presence of skilled labour made it possible for merchants and jewellers to adapt their products to the market they were intended for. While Indian goldsmiths developed a technique called jadau—a gold fillet inserted between the stone and the jewel ‘polki’—that enhanced the beauty and size of uncut, irregular diamonds, their European counterparts relied on cutting in order to enhance the refracting abilities of the gems.

After the discovery of natural diamonds in Brazil and Africa between the 18th and 19th century and the extinction of Indian mines, the availability of Indian gems declined. Yet, this did not mean that India stopped playing a role in the diamond industry. From the 1950s, thanks to cheap but highly skilled labour, the country has established itself as the most important location for processing diamonds. Today, more than 90% of diamonds are cut and polished in India—predominantly in Surat, Gujarat—where they then reach the local market as well as the international one.

Diamond Journey from Mines to Markets

Illustration: Squadron 14; Photograph: Venus Jewel

Natural diamonds come from a finite number of places that include Canada,

Botswana, Russia, and South Africa. Currently there are 30 mines in active production and only seven are classified as Tier 1 deposits with over US$20 billion in reserve. Botswana’s Jwaneng mine, opened in 1982, is one of the richest mines in the world producing around 10 million high-carat diamonds per year. Mines, unlike diamonds, are not forever. Once the end of their productive life is reached, they are closed and a responsible mine restoration process, such as reforestation and land rehabilitation, can begin.