The Hope Diamond: The Cursed History and Science of the Priceless Blue Gemstone

GIA scientist Dr. Sally Eaton-Magaña gets unprecedented access to one of the world’s most famous gemstones — the Hope Diamond.

Gemological Institute of America

|

A gemstone of legends, kings—and scandalous superstitions—, the Hope Diamond is one of history’s most famous diamonds. This 45.52 carat fancy deep grayish-blue diamond has an incomparable history and an extraordinary combination of physical properties. During its long, and allegedly cursed lifetime, the Hope Diamond has intersected with the French monarchy—Kings Louis XIV through XVI—, and likely the British monarch King George IV. The Hope Diamond has been owned by wealthy merchants and some of the most well-known individuals within the jewelry world, including Pierre Cartier and Harry Winston.

A tiny fragment of midnight sky, fallen to earth and still aglow with star gleam.

– The Washington Post, 1947

A Closer Look at the Hope Diamond

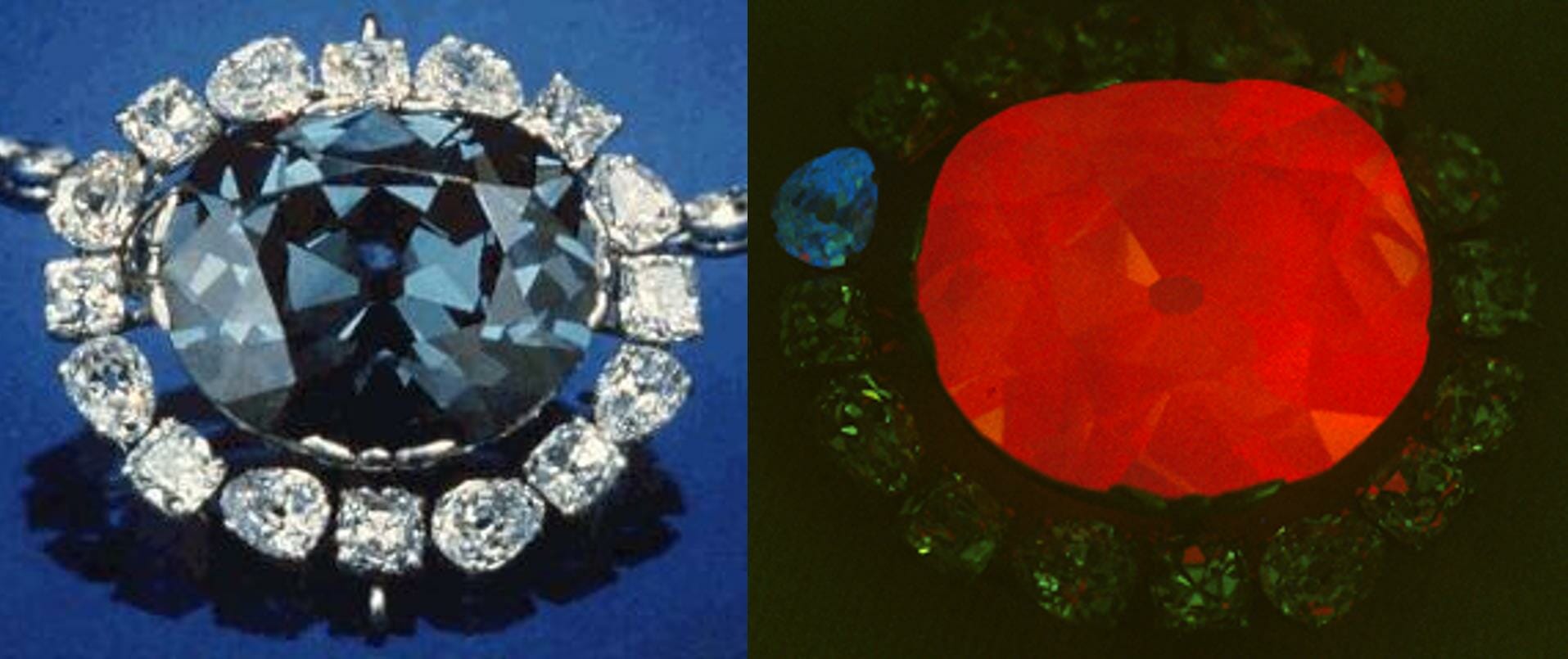

In 2005, I was fortunate to be part of a research team that documented and researched the Hope Diamond’s red phosphorescence, which was previously observed many times before, yet never fully investigated. Those heady days were an exciting opportunity for me; it was enthralling to hold this singular stone and come so close to its incomparable story.

The History of the Hope Diamond

The Hope Diamond got its name from one of its first documented owners, Henry Philip Hope, a wealthy British banker and an avid collector of gems and paintings. Included among Hope’s holdings when he died, the diamond was passed down through this family until 1901 when it was sold to a jeweler. Then, it traded hands several times until it was bought in 1912 by Evalyn Walsh McLean, a Washington, D.C socialite, who owned it until her death in 1947. Harry Winston owned it for the next eleven years until he donated the Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian Institution in 1958. Now, the gem belongs to all Americans.

So how did the story of this illustrious diamond begin? It all goes back to the Tavernier Blue, a 115 carat blue diamond that was brought from India to France, and purchased by the “Sun King”, King Louis XIV, in 1673. The stone was re-cut by his royal jeweler into the 69 carat French Blue, and fashioned with a gold backing that allowed the “sun” to shine within is central field of blue.

This beautiful blue diamond was stolen during the French Revolution in 1792. Twenty years later, a smaller (although still spectacular) 45 carat blue diamond surfaced in London. This diamond, which ultimately became known as the Hope Diamond, appeared just days after the twenty-year statute of limitations for crimes committed during the French Revolution had passed. However, there is little information about who might have done the re-cutting of the gemstone. Although it had been speculated for decades that the lost French Blue and the Hope Diamond were actually the same stone, convincing evidence was not presented until the mid-2000s.

Read More: The Science of Colored Diamonds

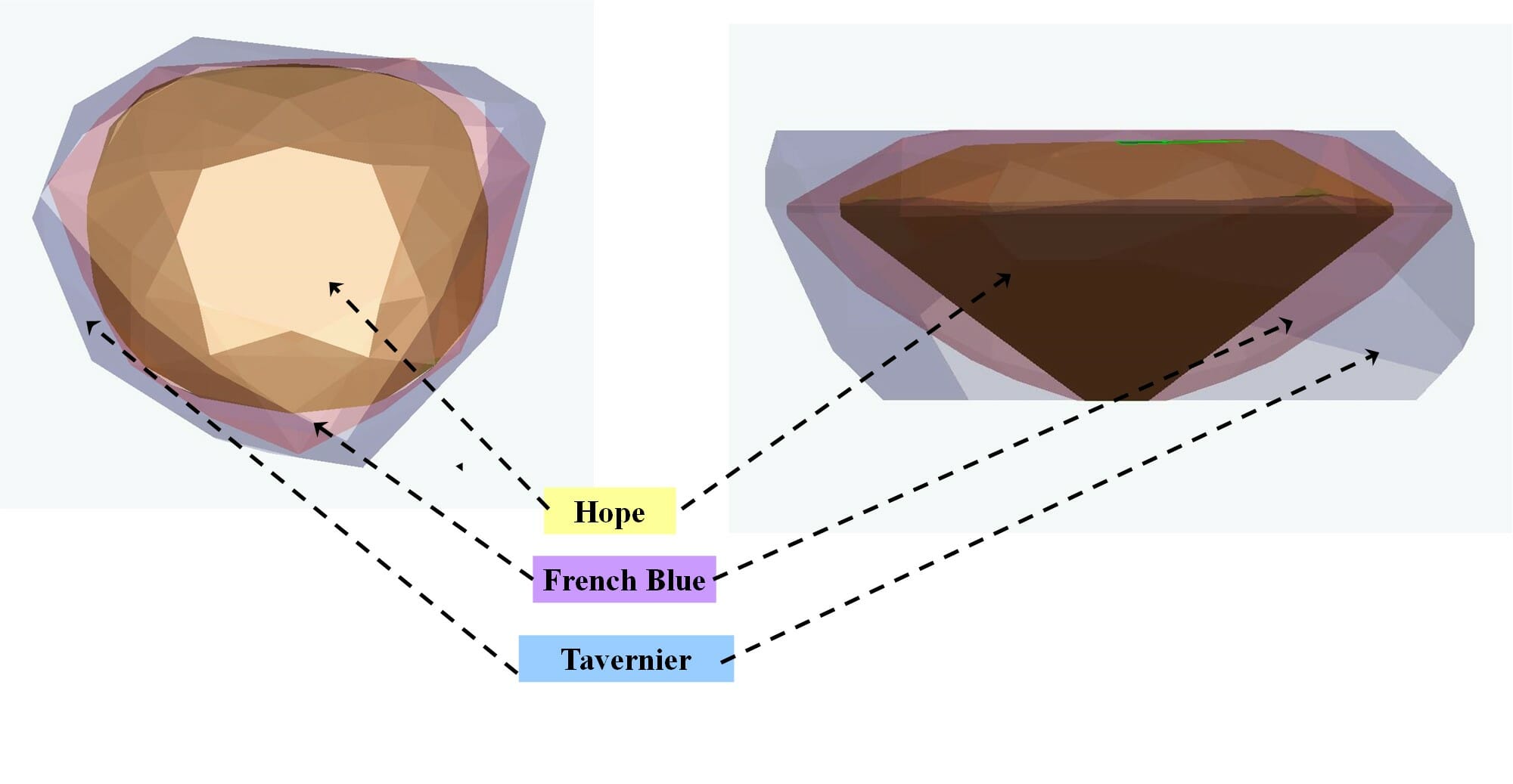

Realistic replicas of the 115 carat Tavernier Blue (the original blue diamond that was presented to King Louis XIV) and the 69 carat French Blue were created. Computer models were produced of all three diamonds to verify that the Hope could be wholly contained within the French Blue. Some of the cutting decisions of the Hope Diamond, such as its asymmetric shape, were best explained by its prior history as the 69 carat French Blue.

The Science of the Hope Diamond

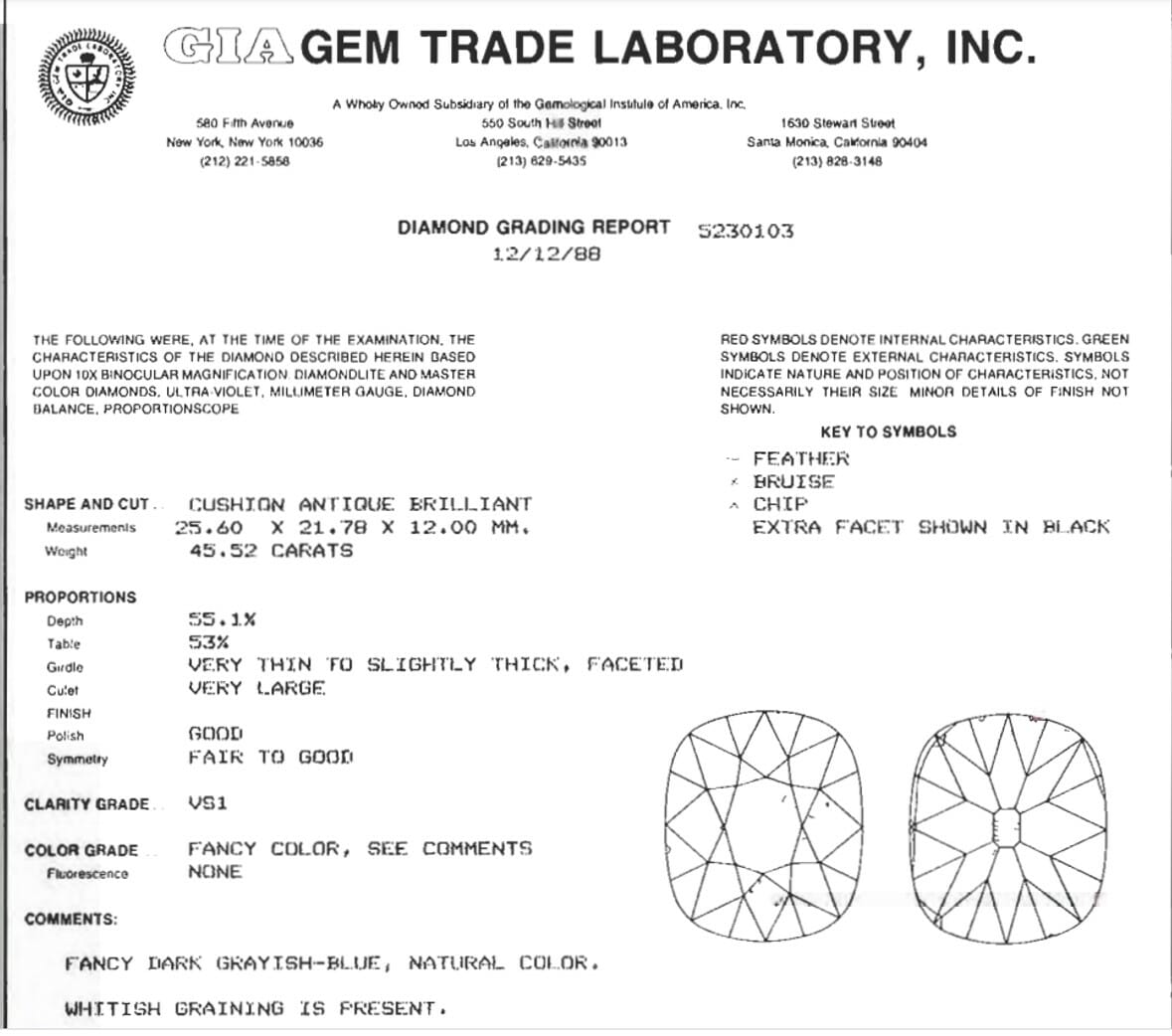

So what was so special about the Hope Diamond that it attracted such prestigious and royal attention? Well, for starters, the Hope Diamond was graded by the GIA in 1988 and in 1996 as a 45.52 carat diamond with a cushion shape with antique brilliance, VS1 clarity and a Fancy Deep grayish-blue color (the result of an incredibly high concentration of observable boron impurities determined as about 1.7 parts per million).

The vast majority of natural gem diamonds (about 99%) have high amounts of nitrogen impurities, with the remaining 1% having little-to-no detectable nitrogen. Less than 0.1% of diamonds—including the Hope—have detectable boron; among these, the vast majority have lower quantities of boron than the Hope Diamond, with most ringing in with less than 0.5 parts per million. Therefore, any natural diamond with such a high quantity of boron is exceedingly unusual, and the occurrence within such a large diamond is truly rare.

Another extraordinary trait of the Hope Diamond is its fiery red phosphorescence. When the diamond is exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, the diamond will glow like a burning ember for longer than a minute. Like the diamond’s blue color, the red phosphorescence is also related to the boron that was incorporated into the diamond while the gemstone formed. When exposed to short-wave UV, those boron atoms interact with other impurities within the diamond that cause the gemstone to emit visible light. The vibrant red glow, coupled with its extended duration, makes this trait quite distinctive for the diamond.

Though superstition and suspicions of a curse have surrounded the history of Hope Diamond for decades, scientific examinations of the diamond—particularly over the last twenty years—have exposed many of its long-held secrets. Such recent research endeavors include the computer modeling that convincingly demonstrated its origin as the French Blue, spectroscopic details and origins of its phosphorescence, plus determination of both its total boron concentration and its observable boron concentration.

Although this diamond passed through many hands before arriving at the Smithsonian where it will continue to captivate millions of visitors, it is fortuitous that this gemstone found its name from one of the first documented owners—Hope. The concept of hope is a universally human sentiment and a fitting appellation for this priceless gem.

Dr. Sally Eaton-Magaña is a GIA (Gemological Institute of America) Senior Research Scientist specializing in natural diamonds, diamond color, treatments, and identification of lab-grown diamonds.