Dirt to Sparkle

Here’s your handy map to trace the exciting journey of natural diamonds from dirt to sparkle.

Miracles of nature perfected by human ingenuity, diamonds symbolise everlasting value. Like most precious things, a diamond takes time, care, commitment, and exceptional artistry to travel from a mine to your finger. If you’ve ever wanted to trace this exciting journey, here’s your handy map.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock – pun intended – you already know that a diamond is a pure carbon, compressed 100 miles below the Earth’s surface over a billion years ago. The eye-popping sparkler on your engagement ring is probably one of the oldest things you’ll ever touch, like a mysterious geological time capsule narrating stories of our planet’s resilience. A diamond’s relationship with human beings takes several twists and turns, from the quest to extract it, all the way to your jewellery wardrobe. For a discerning, post-pandemic consumer, this journey offers a rich lineage of human skills and state-of-the-art technology working in tandem.

Mining – Extracting the Earth’s oldest treasures

Natural diamonds are formed under the Earth’s surface at extreme pressure and scorching temperatures of above 1000 degrees Celsius. Imagine the process in dramatic slow-motion – volcanic rocks (kimberlites) bearing diamonds, incorporating into scalding magma and bubbling up from unimaginable depths. 80% of the world’s diamond supply comes from Botswana, Canada and South Africa, where mining involves years of research and investment. In return, it positively impacts local communities by providing education, employment, and healthcare, with a long-term vision for sustainable development. Together, seven natural diamond companies – Petra Diamond, DE Beers Group, RZM Murowa, Arctic Canadian Diamond Company, Rio Tinto, and Lucara Diamond – protect more than 643,000 acres of wilderness globally. A heartening example of this environmental stewardship is the deposits in remote Siberia, which paved the way for the development of the Mirny ‘diamond capital’ with hospitals, schools, and a 79000-acre conservation park protecting an array of flora and fauna including the native foxes which had unexpectedly led geologists to discover kimberlite pipes in 1955.

Major natural diamond producers have publicly declared their commitment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, aimed at 2030. Transparency across the supply chain is being encouraged right at the source. Prerna Khurana of Amritsar-based Khurana Jewellery House cites De Beers’ recent initiative, The Tracr program – designed to create a passport for each mined stone to ascertain their conflict-free nature – as a very important advancement for the industry, paving the way for more transparency right from the beginning. This trust percolates through the supply chain, right up to the post-pandemic, conscientious retail buyer. “Proof of a diamond’s origin offers the peace of mind that a consumer desires before making a purchase,” Khurana affirms.

Transforming Diamond Rough into Precious Gems

Finding a real gem in diamond rough is an arduous expedition. Mining companies sell their rough to sightholders/intermediaries who take it forward to processing and cutting. At a processing center, the kimberlite ore undergoes a series of procedures – Blasting, Crushing, Screening, Scrubbing, and Concentration, in which the ore is mixed into a ferrosilicon slurry and fed into a dense media cyclone where all the heavy minerals sink to the bottom and the dirt floats. Modern flowsheets with X-Ray sorters are used to minimise waste – diamonds fluoresce in X-Ray light – and the ferrosilicon is reused. The minerals are then sent to belts or vibrating tables where specially formulated grease captures the diamonds. It takes more than 250 tons of ore to produce just one carat of diamond rough. If that doesn’t sound selective enough, consider this: only a quarter of that rough is gem quality. (Approximately 46% of the world’s natural ‘diamonds’ – are allotted for industrial use) Your gem-quality diamond literally emerges like a lotus from the mud.

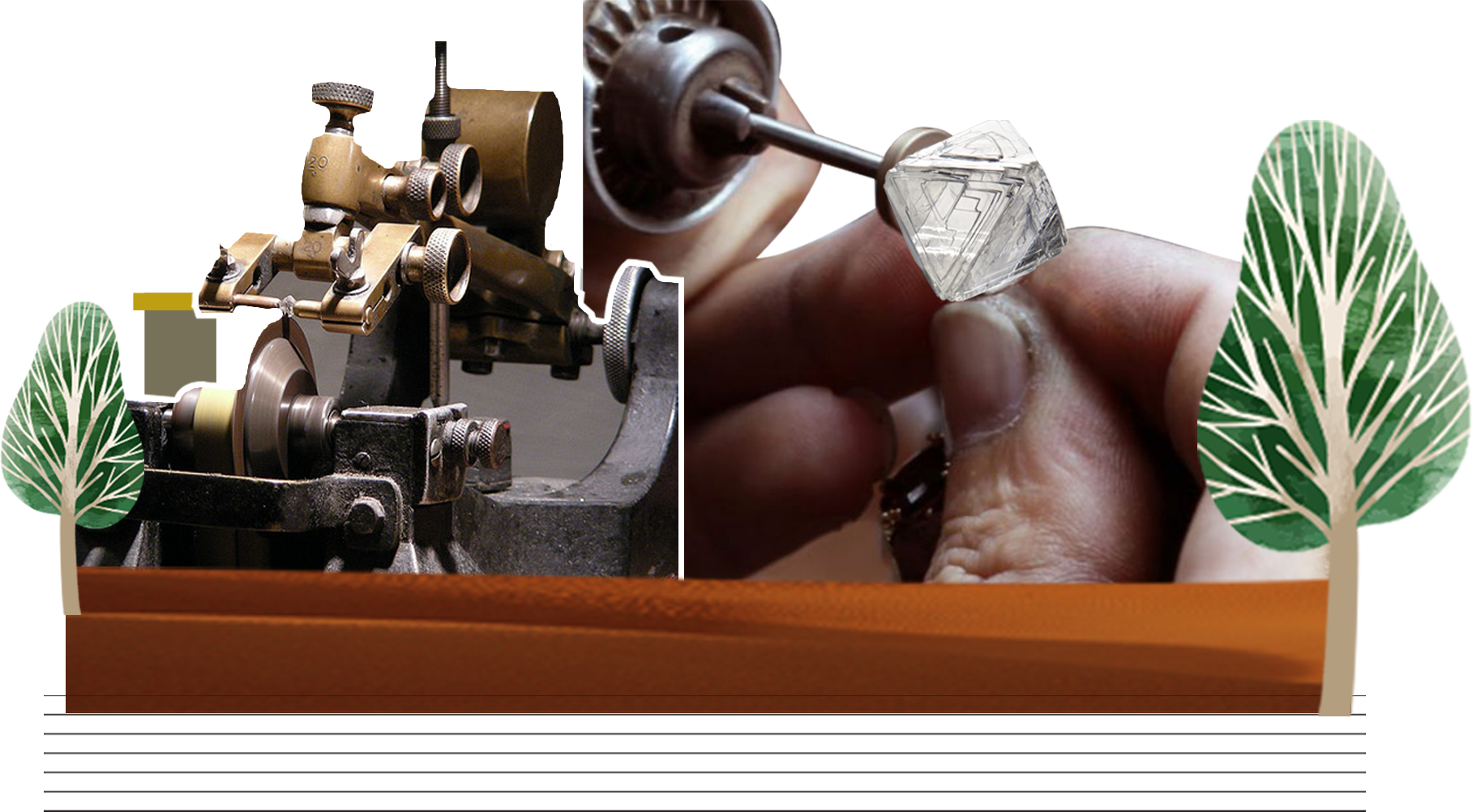

Cuts and Glory: Crafting Diamond Rough into Brilliance

Carving a diamond rough into a thing of great beauty is often compared to the relentless hardships that a human being must endure before ‘shining’. Gem quality diamonds are distributed to Antwerp, Tel Aviv, New York, Johannesburg, China, and Thailand, but the diamond cutting and processing industry is dominated by India. It is estimated that 11 of 12 diamonds in any piece of jewellery across the world are cut in India. (The diamond cutting industry boomed in India between the 1960s to 1990s, thanks to the easy availability of trained skilled labour as well as the enterprise and grit of the diamond merchants in India, who broke into the world trade by starting with small and medium-sized diamonds.) While Mumbai is a major trade hub, the heart of the cutting industry lies in Gujarat; not just Surat – where the hira karigar with his ghanti (polishing wheel) is a historic figure – but across rural and tribal hamlets, generating employment for local entrepreneurs and marginalized communities. At a cutting center, a disciplined line-up of extremely specialized artisans – with the aid of technology – begin working their magic on your stone. The first – crucial and time-consuming – stage is Planning when a Cutter determines the best possible shape for the diamond to reduce wastage and maximize the yield of the rough. This is achieved via groundbreaking 3D rough planning computer simulation technology which leaves no room for error.

The Cutter then divides the rough into smaller pieces by Cleaving, Sawing, and Laser Cutting. The pieces are passed to a Girdler who uses Bruting techniques to shape the outline of the stone, Then, a Blocker cuts and polishes the first 18 facets of the stone. The Brillianteer – an appropriate name for this artist – intricately cuts and polishes 40 facets including the star, upper and lower girdle. Finally, the diamond is boiled in acids to remove dust and oil. From here, they are ready for 24 registered diamond bourses across the world to be sold and traded, armed with their certificates. “Blockchain technology is now being used to provide secure supply chain certification by global enterprises such as Everledger and IBM. says, Khurana. “The internal fingerprint of every diamond is captured by shooting a high-intensity laser into the stone. The unique number of the diamond is inscribed on its girdle, with the exception of Forevermark diamonds which bear the number on the stone’s table. In case, the customer loses their diamond certificate, they can retrieve it online or through the retailer with the help of this inscription.”

Set to Mesmerize: Designing Diamond Jewellery

While a certificate traces a diamond’s journey, it can’t fully reflect the incredible individuality of your sparkler. “A certificate can’t quantify the nuances of a diamond’s beauty like it’s fire which is sometimes brilliant even in the case of a lower grade piece like a VVS2 or VS1,” enthuses Tara Daswani of Tara Fine Jewellery. This beauty is further enhanced when skillfully set into a piece of jewellery. Daswani – whose contemporary designs require her to custom-calibrate diamonds, especially her beloved irregularly-shaped baguettes – breaks down the process of designing a piece of diamond jewellery into four specialties – Manual/Computerised Sketching, Sorting, Setting and Polishing – which take around four weeks to slip from a piece of paper into your finger. Daswani relies on the experienced eyes and hands of her karigars’ (Indian craftsmen) at every step. “We need a machine to polish the final piece, but it takes a human to hold it at the right angle and choose a softer, delicate brush for a mirror finish”. While aided by smart, digital design, “It’s a karigar who infuses the soul into every piece of jewellery,” she avers.

Value-driven Innovation

Like all memorable adventures, the old-soul journey of diamond benefits from unforeseen turns and twists. Vinod Hayagriv of C. Krishniah Chetty & Sons is bullish on the adoption of technology across the supply chain, from 3D printing and new finishing techniques to high-end crafting. Their Bangalore-based, 150-year old heritage brand has spent considerable time designing an expensive proprietary cut – the Sesquicentennial Cut by C. Krishniah Chetty Group – currently pending patent registration. “We need to step up with innovative design concepts and tech-assisted manufacturing, while relentlessly fine-tuning the entire processing and designing cycle and working on transparency at every stage,” he says. Even as the technology works simultaneously with human skill and experience, ethics remain at the core of customer trust. “Processes need to be driven by values,” Hayagriv emphasizes, “not profits.”

Stories for eternity

Your diamond’s physical journey from mine to processing and cutting units to designer concludes when it adorns you. But even after it rests on your finger or ear, its emotional journey continues unabated. “Diamonds never go out of style. Your diamond jewellery is versatile, you can melt it and reset the diamonds,” says Daswani. Whether set in classic or contemporary design, diamonds are timeless heirlooms, holding magical tales of faraway communities, heritage craftsmen with magical hands, and evolving state-of-the-art technology, all culminating in a glistening little package that captures your imagination. Passed down generations – from parents to children, gifted by loving spouses and siblings or bought for oneself, denoting a financial coming of age – a diamond’s journey is never over; it continues to travel, from one heart to another.