From Golconda To Russia: The Legend of the Diamond with Two Names

In a world where the only constant promise is change, this natural diamond has transcended history, owners and the names they adoringly bestowed upon it. This is the story of the Great Mughal Diamond, known today to the world as the Orlov.

Illustrations By Shawn D’souza

Image Credit: Alamy

You could say that extraordinary natural diamonds were only part of what the Golconda mines produced. The other thing that came out of these muddy crevices in the earth south of the River Krishna is legend. And in this series we explore the many legends that spun around the magnificent Great Mughal Diamond.

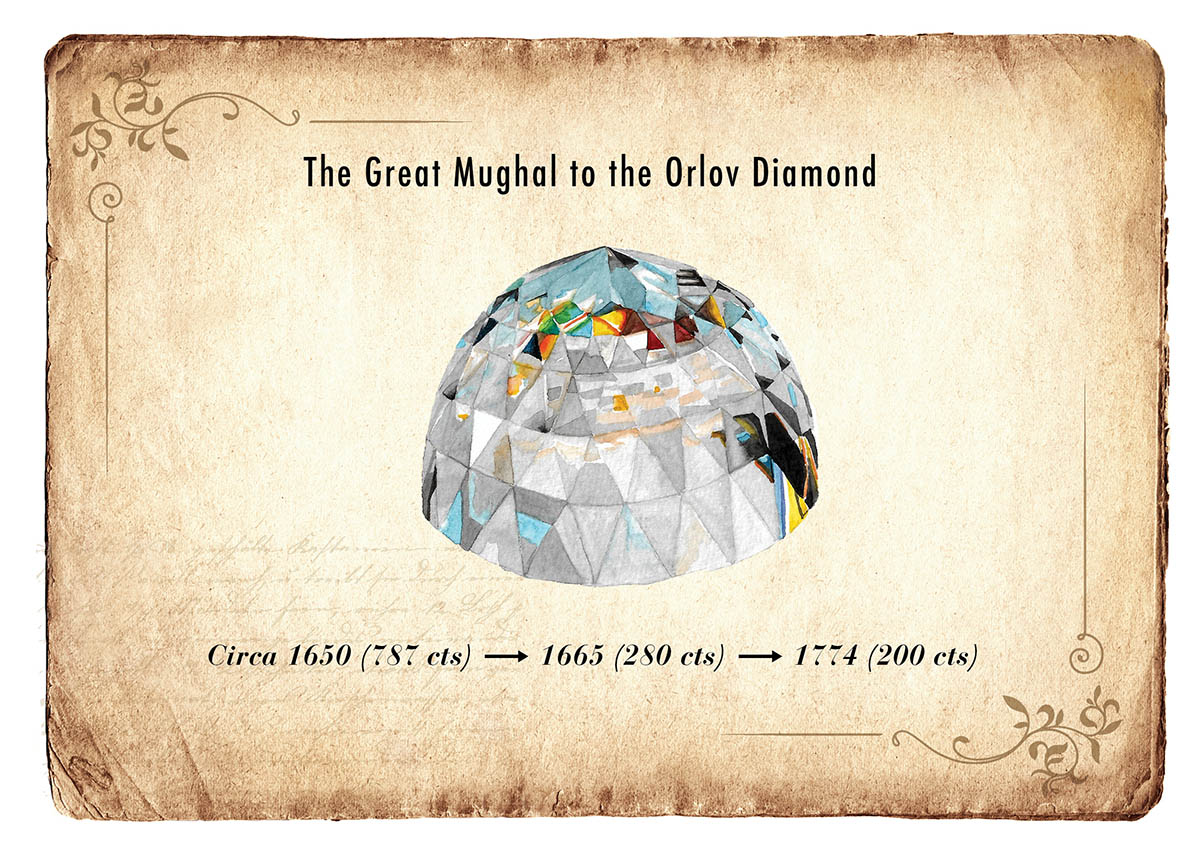

The name wasn’t just hyperbole. At 787 carats, it was believed to be the largest natural diamond ever discovered in India. The stone was mined in Golconda in 1650 and owing to its grand size, gifted to Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan by a minor noble seeking an alliance with the mighty ruler of the subcontinent. Its size was certainly impressive, but the rock wasn’t without flaw. And to get rid of the small inclusions in it, the emperor employed Hortentio Borgis, a Venetian lapidary, to cut and polish the rough stone. It proved to be a decision Shah Jahan would live to rue. Borgis ground away at the stunning gem, getting rid of every inclusion he could find till the stone he was left with was greatly diminished in size. Upon surveying Borgis’s handiwork, Shah Jahan was said to be so displeased with what the Venetian had done with his prized gem that many believed the emperor would have the lapidary’s head. Although saved from such a brutal end, Borgis was fined every last rupee of the 10,000 he possessed at the time.

The diamond was now around 280 carats, its unusual domed shape cut like a rose, the form that Mughals preferred for their precious gems. When Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a French jeweller and traveller well acquainted with Golconda gems, saw the rock in 1665, he said that it looked as if someone had cut an egg in half. It had an almost flat bottom and Tavernier noted a slight crack and an intrusion around the base that made it immediately recognisable. The Frenchman referred to it in the notes that he jotted down alongside a drawing of the gem as the “great diamond”.

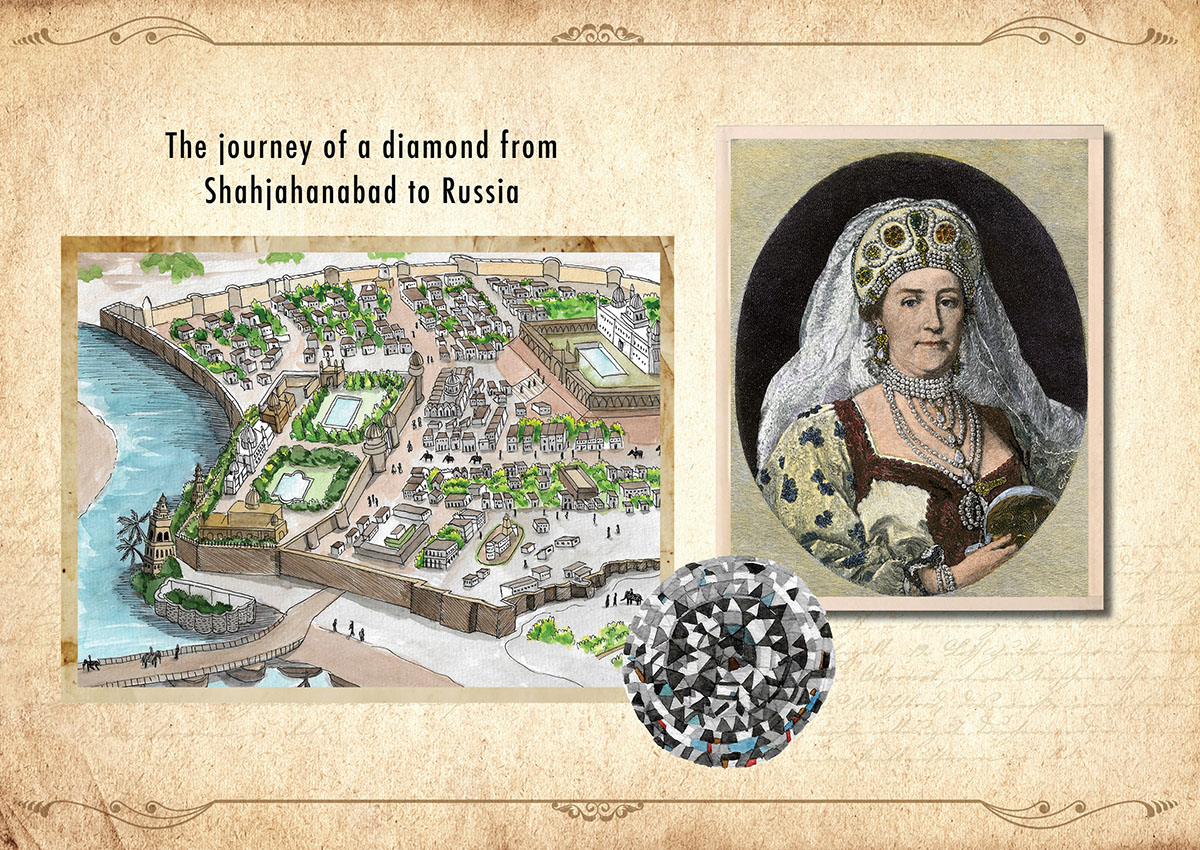

It remained a prized Mughal possession for generations till Nader Shah, the Persian invader sensing a wane in Mughal military strength, invaded the land, sacking cities like Lahore and then the capital, Delhi. When he finally left, having pillaged and looted, he took with him most of the empire’s riches, including the Great Mughal Diamond. He kept it on him when he rode back to Isfahan in the heart of Persia. But when he was assassinated not long after in 1747, the legendary Great Mughal Diamond simply vanished.

Just as mysteriously as the Great Mughal Diamond disappeared, so did Orlov diamond appear. Remarkably similar in shape and cut, but at under 200 carats, the Orlov was a fair bit smaller. Because so little was known of its origins, wild legends began to be whispered about it. According to one of the more popular ones, the diamond was originally part of a twosome that formed the eyes of an idol inside a temple close to Mysore. A French soldier who had deserted his forces in the Carnatic Wars in the 18th century came to hear about it. One stormy night, with thunder roaring and lightning shrieking, he managed to prise one of the rocks free from the idol. But his nerves gave away before he could get the second gem and clutching just the one diamond, he jumped the temple wall and escaped to Madras. There he sold it off to an English sailing captain for £2,000. Then, legend goes, the rock voyaged around the world, stopping off in various European capitals, eventually making its way to St. Petersburg and the royal household of imperial Russia. While this story is probably more fiction than fact, the more verifiable origin story of the Orlov is no less extraordinary.

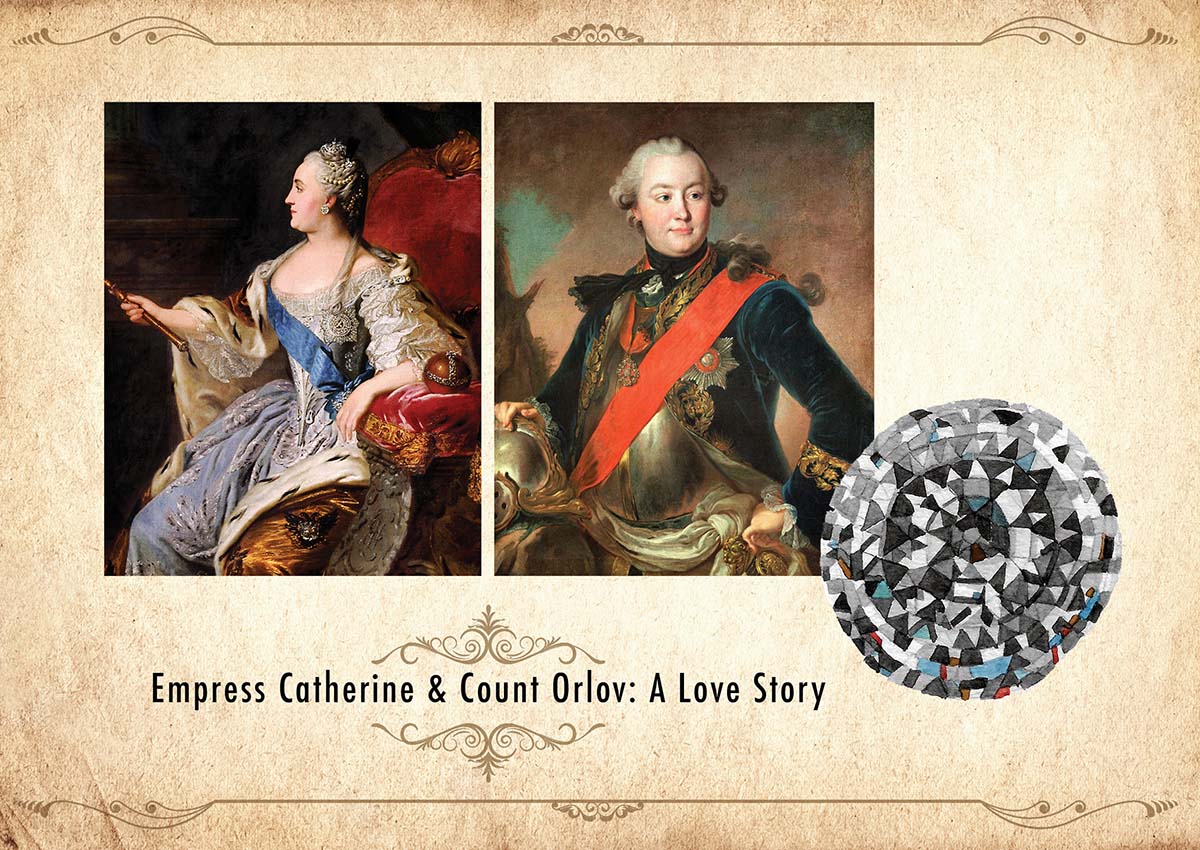

Today most gemologists believe that the Orlov is none other than the Great Mughal Diamond. Upon Nader Shah’s assassination, his coveted rock was stolen and ended up being sold to a wealthy Armenian with a keen eye for the most precious gems. Word spread through the corridors of royal families in Europe about this rarest of rare diamonds. It wasn’t long before Catherine the Great, the empress of imperial Russia at the time and a connoisseur of fine gems, heard about it. The rocks were her weakness and it is reported that she even named her favourite horse Diamond. But the price the Armenian quoted for this particular gem was so astronomical that it made even Catherine, one of the richest and most powerful monarchs in history, balk. All she knew was that she had to have this, one of the finest examples of a natural diamond in the world. However, she did not think it proper to be seen trying to procure such an extravagant gem and she certainly thought it beneath her station to be negotiating with a jeweller. So clearly, this most delicate of tasks of procuring the gem, privately and quietly, was for her most trusted of advisors.

She dispatched Count Grigory Orlov, the man who helped her ascend to the throne, her closest confidante, her lover and someone completely dedicated to Catherine. He made his way to Amsterdam where he managed to finally procure the gem for her in 1774. But when he returned to St Petersburg with it, the city was rife with gossip. Orlov had bought the empress one of the largest natural diamonds in the world and Catherine had named the invaluable gem after him. Naturally, people whispered. Surely, this was admission of their deep love for each other, some said. Others thought it was the count’s last-ditch attempt to rekindle the great love he had shared with the empress, one that had lately been fizzling out.

Catherine was enamoured with her prize possession, resplendent in its original Mughal rose-style cut, its 180 sharp facets reflecting even the faintest glimmer of light to illuminate entire rooms, a delicate bluish-green tint rising from its depths.

Never mind that the gem, one of the most valuable in the world, was way beyond Orlov’s means. To everyone in Russia, it was a token of their very special relationship. No one ever found out at the time that the empress had in fact paid for the gem, through Orlov.

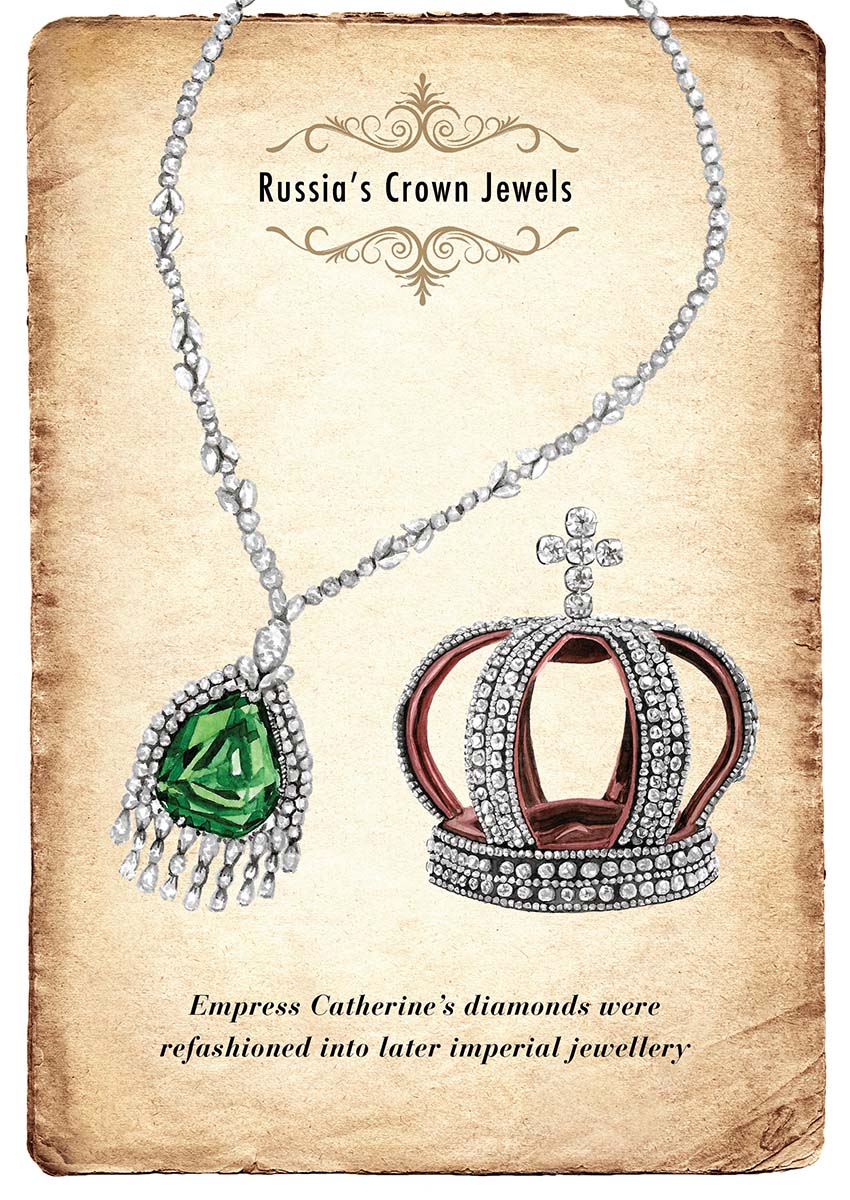

It was placed onto the staff, surrounded by a halo of smaller diamonds, under the motif of the golden double-headed eagle, the symbol of the monarchy with the Romanov family’s coat of arms emblazoned on the mythical bird’s breast.

From then on, the sceptre, along with the Imperial Crown of Russia, also designed specially for Catherine’s coronation and covered in 4,936 diamonds, became the symbols of royal power in the country. And it remained the standard for every emperor of that great world power till 1917 when the monarchy ended abruptly with the Russian Revolution. Today, the Orlov sits with other crown jewels at the Diamond Fund in the Kremlin Armoury, vestiges of a time of immense grandeur and opulence.

Like every gem of note born in the mines south of the Krishna river billions of years ago went on to become inextricably linked to the modern history of humanity, this monumental diamond is no exception. It has had many names; the Great Mughal Diamond, briefly the Amsterdam Diamond and now, the Orlov. Through the ages few things have remained constant—its sheer brilliance as one of the finest natural diamonds ever mined and our fascination with it. Neither of those will go away any time soon.