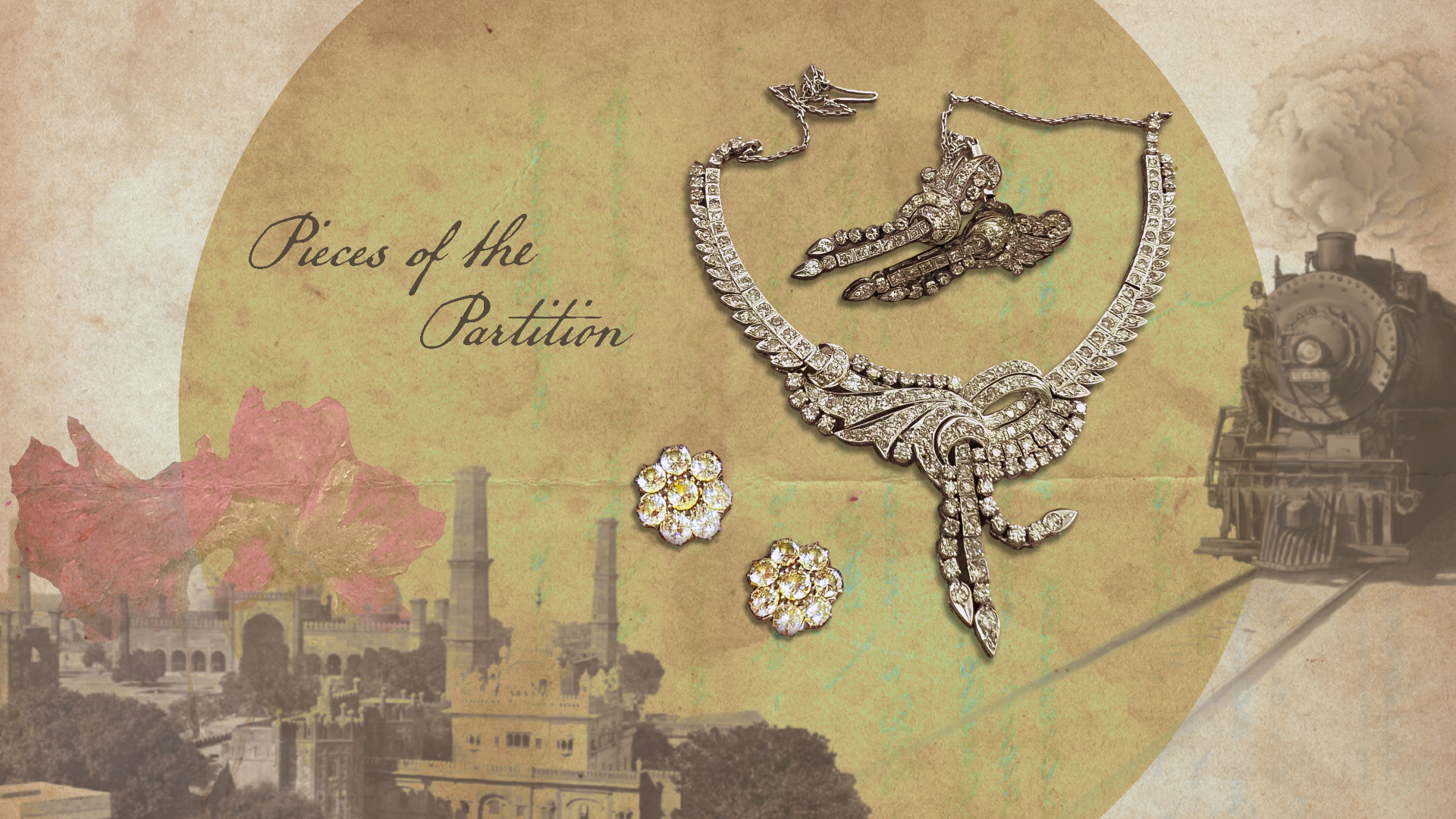

Pieces of the Partition: The Diamond Heirlooms That Live On

Among the many objects that people carried across the border were natural diamond jewels, laden with memories and symbolising a home that was.

Aug 14, 1947:The drawing of the Radcliffe Line didn’t just shape nations—it altered the very idea of home and belonging for those forced to migrate to either side of the border. The largest mass migration in history, the Partition of India forced millions to leave behind a home that now lives only in memory, with merely a fraction of them fortunate to have been able to flee with more than just the clothes on their back…

Growing up in Delhi, Nanki Kaur often spent her afternoons by her Dadi Prabhjot Kaur’s dresser, marvelling at all the glittering curios scattered across the counter—many of which were precious items she had inherited from her mother and grandmother. Among these was a ruby and diamond ring that belonged to Nanki’s great-grandmother, truly a piece of history.

“My Dadi often wore the ring after expertly tying her saree, strapping on her heels and putting on a last coat of mascara before heading out,” shares 27-year-old Nanki, still fascinated that her grandma wears her grandma’s ring! “Whenever I asked her about her attire, she’d mention the ring: ‘This was my Dadi’s ring. Can you imagine?’”

The Kaur family traces their ancestry to pre-partition Lahore, where Prabhjot’s grandfather worked as an advocate. While for Nanki, the elegant diamond ring symbolises her close bond with her Dadi,for the 76-year-old, it keeps her connected with her paternal grandmotherand memories of life in Lahore.

“Amrit Kaur, my Dadi, was a remarkable woman—strong, independent, educated, talented and social, with a prominent social circle in Lahore,” recalls Prabhjot Kaur. “Dadi was particularly brave when the country was being divided. She even drove the family car across the border into East Punjab! So, every time I wear the ring, I’m reminded of her bravery and often hope I was bestowed with traits like hers.”

Like Prabhjot, her daughter-in-law—and Nanki’s mother—Parbeen Kaur, too, inherited a beautiful diamond and ruby set from her grandmother, when she got married three decades ago. The sparkling natural diamonds and Burmese rubies represent a special connection with her grandma, Prakash Kaur.

“I have memories of my Dadi often wearing the set, both before and after the Partition,” says the 52-year-old. “As she died when I was fairly young, it helps me cement the few memories I have of her in my mind and makes me feel as though she’s always looking over me.”

This is perhaps why Parbeen, when regaling Nanki with stories of their ancestry, laid particular emphasis on this set, the natural diamonds gleaming against the bright rubies. And Nanki, who loves to wear these jewels on special occasions, was raised to be proud of their history and the items that connect them across generations.

“These pieces of inheritance hold within them not only the struggles of the Partition; they also represent resilience, our familial bond and perseverance,” Nanki says. “Every time I wear them today, I’m reminded of the strong line of women I come from and the responsibility I and our future generations hold to value, respect and carry on their empowering legacy.”

These objects carry history — they’ve survived history

What these pieces of history represent, beyond their aesthetics and monetary value, is a deeper connect with their ancestors, their roots and final place of settlement. The physicality of these heirlooms secures a relationship with the past and serves as a conduit to a memory, individual or event in history—in this case, the Partition.

As Aanchal Malhotra says, these migratory objects carve a pathway into the past. By tracing the material memories of families with history across the border, the author of Remnants of a Separation (and co-founder of the Museum of Material Memory) hopes to evaluate the generational impact they had and delve deep into the emotions such heirlooms kindle.

“I don’t believe there’s any one blanket emotion that Partition survivors feel towards heirlooms,” she explains. “They can either be emotionally attached or feel no value towards them. But when it’s an object from such a tumultuous past and the story is shared, it makes a huge impact. These objects have a life of their own. They’ve seen things. They carry history; they’ve survived history.”

In Malhotra’s eyes, an heirloom tells a story of family ties and the strength with which one clings onto them. They represent shared sentiments and intriguing alternative histories of the Partition, seeped in a bond that survived loss, displacement and cross-generational differences.

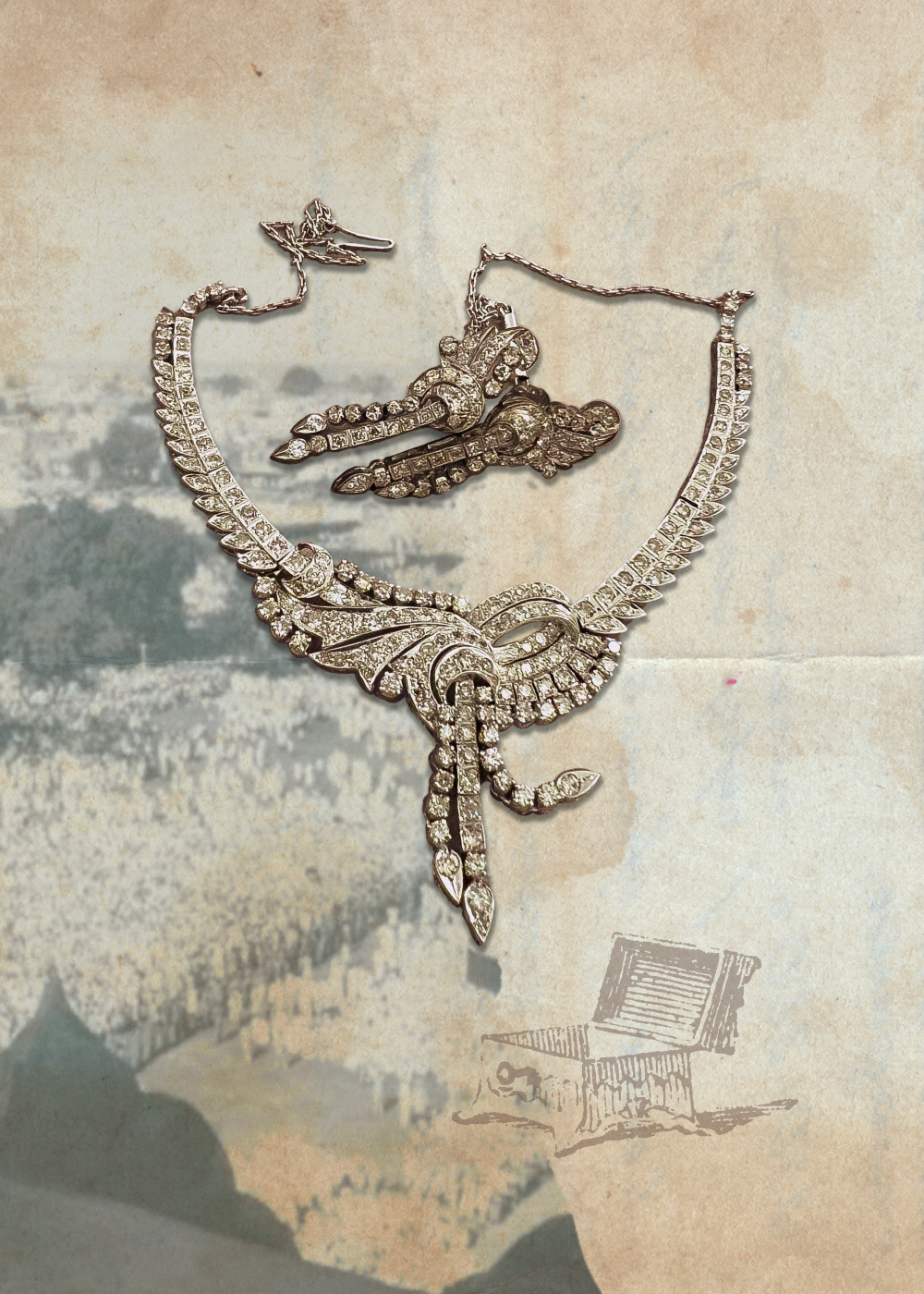

This is the case for Delhi-based socialite Guneeta Dhingra. The opulent diamond set she inherited from her maternal grandmother holds a special place in her heart.

“My maternal grandparents, first settled in Iran, had to flee to India from Rawalpindi. They were able to carry their personal belongings with them… Their clothes, silver and papers… Among these, my grandmother brought along all her jewellery, which included Kundan, diamonds and gold,” Guneeta says. “It was from these that I received her diamond set… I attach a lot of value to this set because she’s no longer with me. But having such pieces of jewellery she once wore reminds me of her.”

Similarly, for journalist and poet Radhika Sachdev, the floral Belgian-cut diamond studs she inherited from her mother-in-law, Lakshmi Gobindram Sachdev, reminds her of a pair that belonged to her mother. Radhika’s mother received these Sindhi Kokas—as the floral cuts are traditionally known—from her parents during her wedding.

“When my mother mentioned ‘Belgian-cut’ to her brother-in-law, he nicknamed her vilayati cut!” recalls Radhika, who maps her roots back to Sindh; her father’s side (the Bathijas) belonged to Shikarpur, while her mother’s family (the Kukrejas) was based in Karachi. “I want to retain the floral design and turn them into pendants for my two daughters.”

Isn’t that what makes a diamond, a diamond?

Like Radhika and her daughters, many have opted to lend a more contemporary appeal to these pieces of the Partition, to suit the tastes of future inheritors. As a jeweller, Tarang Arora, Creative Director of Amrapali Jewels, can envision several ways in which such gems can be repurposed, but he “personally wouldn’t touch such heirlooms because of the history associated with them.”

“If diamonds from those days survive to this day, they’re certainly one of a kind. The fact that they’d be made entirely of natural diamonds, perhaps from the Golconda Mines, adds to their worth because of the history they unearth,” he explains. “If it’s a larger piece, I’d probably break it up into multiple pieces for the family. At the time, with low knowledge of techniques, there was a lot of handwork, and it was all more personal. I wouldn’t like to fiddle with that. Instead, I’d perhaps just tweak the workmanship, touch up the enamelling or the missing gold, and simply restore the jewellery…”

“Diamonds hardly chip or face any kind of wear and tear. Isn’t that what makes a diamond, a diamond?” adds Tarang, for whom such heirlooms hold a personal connection—an emotion Akanksha Arora, CEO, Tribe Amparali and his wife, truly understands.

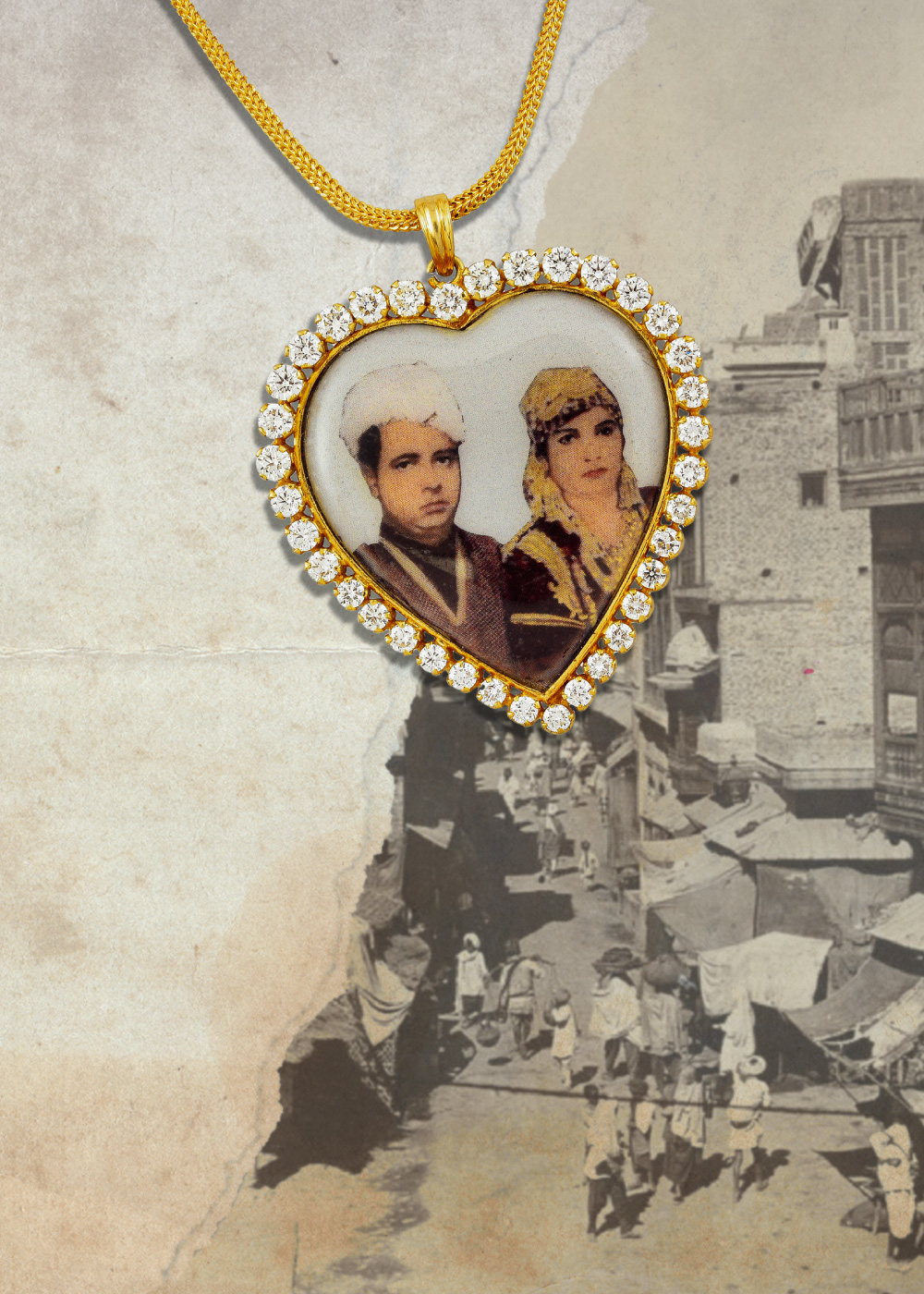

“My grandmother was always very stylishly dressed, with appropriate jewellery to suit the occasion,” says Akanksha. “From her, I inherited a heart-shaped gold locket, bordered with diamonds. It has a photo of her parents (my great-grandparents) hand-painted in enamel in it. I remember her wearing it every day…”

A symbol of our family’s culture

Like the Kaurs who treasure their natural diamond heirlooms as invaluable parts of their ancestry, the Belai family, too, cherishes a solitaire and a pair of Sindhi Kokas. Deepa Chauhan—entrepreneur, home chef and among the top nine contestants of MasterChef India 2023—and her mother, Rupa Belai, trace their roots back to Shikarpur, Quetta and Karachi. The jewels, to them, represent the legacy of Savitri Belai, Rupa’s late mother-in-law.

“Savitri Belai was an amazing, stoic woman, widowed really young with seven children,” shares 77-year-old Rupa. “She was modern for the 1930s she belonged to. Having grown up in Bombay, she wasn’t accustomed to the traditional Sindhi nath that came adorned with emeralds, rubies and pearls. Instead, she preferred to wear a single diamond nose stud that was designed for her during her wedding.”

Today, this natural diamond lives on in the form of a “sizable solitaire” ring, which 52-year-old Deepa says she wore occasionally before getting married. In fact, the ring was nearly scammed out of their family…

Says Rupa: “It’s by some miracle that we got it back. It had to be reset because it got damaged in the time it left the family. Now, I’ve gifted it to my son, Kishore, who wants to preserve it as a physical memory of my mother-in-law and our family history in Pakistan, as a symbol of our culture and inheritance.”

The Sindhi Koka earrings—a set of seven diamonds shaped like a flower—were also part of Rupa’s bridal trousseau, passed down to her by mother-in-law and reset in Calcutta when she got married in 1968. She’s worn them every day ever since.

“We hope to continue to receive her blessings through her material objects,” Rupa concludes.

Any object that survived the Partition—be it a diary, kitchenware, art or jewellery—is particularly special because it not only holds memories of a home that once was, but is part of one’s ancestry, part of the very history of India. And herein lies the story of these diamond-studded pieces of memory, home and hope for new beginnings.