The Master of Light

With brushstrokes that seem light as a feather, Raja Ravi Varma captured the immutable, crystalline shimmer of diamonds in paintings that, even today, inspire.

On a warm summer’s day in 1848, in the town of Kilimanoor in South India, a son was born to an aristocratic family with close ties to the royals of Travancore (present day Kerala). Though no-one knew it at the time, the child, named Ravi Varma, would grow up to be one of the most important artists of his time. Till about 120 years before his birth, just about 1,200 km north east of Kilimanoor, the Krishna River had been washing up some of the world’s most magnificent natural diamonds into the alluvial mines in the Krishna Godavari Delta. These diamonds, as it turned out, would intertwine intimately with Varma’s life and career.

In a 2020 talk on the jewellery seen in Raja Ravi Varma’s paintings, jewellery historian and curator Usha Balakrishnan explained the role of adornment as defined in ancient Indian texts: “The texts state that by adorning the body with beautiful jewels, that which is nirguna (formless and invisible) becomes saguna, that is, it assumes form.” In the context of Varma’s paintings, she added, “Figures actually become saguna—they come alive with the jewels that he so beautifully adorns his subjects with.”

Varma, who was influenced by the multi-layered style of the Tanjore school, understood adornment like few other artists of his time. But his portraits of diamond-bedecked royals and soft-faced gods and goddesses were more than just artworks—they were a tactile, thoughtful response to the times in which he lived. The world of Varma’s paintings was one of myth and magic—a world created by a man who was delighted by beauty, and happy to share his delight. The wonderful thing about Varma’s art is that it transports us out of our time and place—not just into the world of the artwork, but into the heart and mind of the artist. Even today, more than 175 years since his birth, his paintings still connect with viewers.

Varma showed his artistic inclinations very early in life. A charming anecdote recounted by his great-great-grandson Jay Varma (himself an artist), has Ravi Varma as a child, using charcoal to draw on the walls of the Kilimanoor palace, which an attendant was charged with cleaning up so the young master could continue his artistic explorations. His skills were further honed in the courts of the Maharaja of Travancore, where he would also meet Theodore Jensen, a European artist employed by the royals to paint their portraits.

His royalty-adjacent upbringing gave Varma an insider’s view of some of the world’s most prized jewels, and his artist’s hand and imagination supplied the rest. When he began painting in the Occident-meets-Orient style he came to be known for, he could hardly have guessed that the impact of his work would reach so far into the future. But as recently as October 2022, actress Sobhita Dhulipalia got her helix pierced, citing as her inspiration, one of Varma’s paintings. If he were alive today, he would be flattered and possibly a little bemused by this turn of events.

In the few portraits that exist of him, Varma looks more like someone’s kind, elderly uncle rather than a revolutionary artist, but he was nevertheless the man who would change the face of Indian art in two important ways. He was the first Indian artist to fuse elements of academic art and Indian themes, giving rise to a vivid, dream-like aesthetic that even today invites emulation. He was also the first Indian artist to have his artworks printed—an act that made his work far more accessible to the public, becoming in the process, an integral part of India’s aesthetic consciousness.

In Varma’s paintings, it is said, you could almost hear the rustle of the silk saris his sitters wore. His paintings not only documented the subtle sheen of silk, velvet and brocade, but the various ways in which different communities across India wore them. Less auditory, but more visually arresting perhaps, was the diamond-studded jewellery that almost leaps out of his works. It sparkles around necks, flashes delicately from ear lobes, noses and wrists, and of course, shines magnificently in tall crowns, amulets and aigrettes. India’s royals had long treasured precious diamonds, for they understood their value—political, seductive and symbolic.

When Varma came to painting portraits of gods, goddesses, and royals, he rendered their diamond-studded jewellery with an intuitive understanding of its form and value. In his commissioned portraits, the jewellery worn by the central figure is as much an accentuation of their physical characteristics as it is a statement of taste, lineage, status and political leanings. In his mythological paintings, his gods and goddesses glow—as much with divinity, as with the diamonds on their bodies in their jewels, accessories and crowns.

Using Diamonds to Transform Gods in Paintings

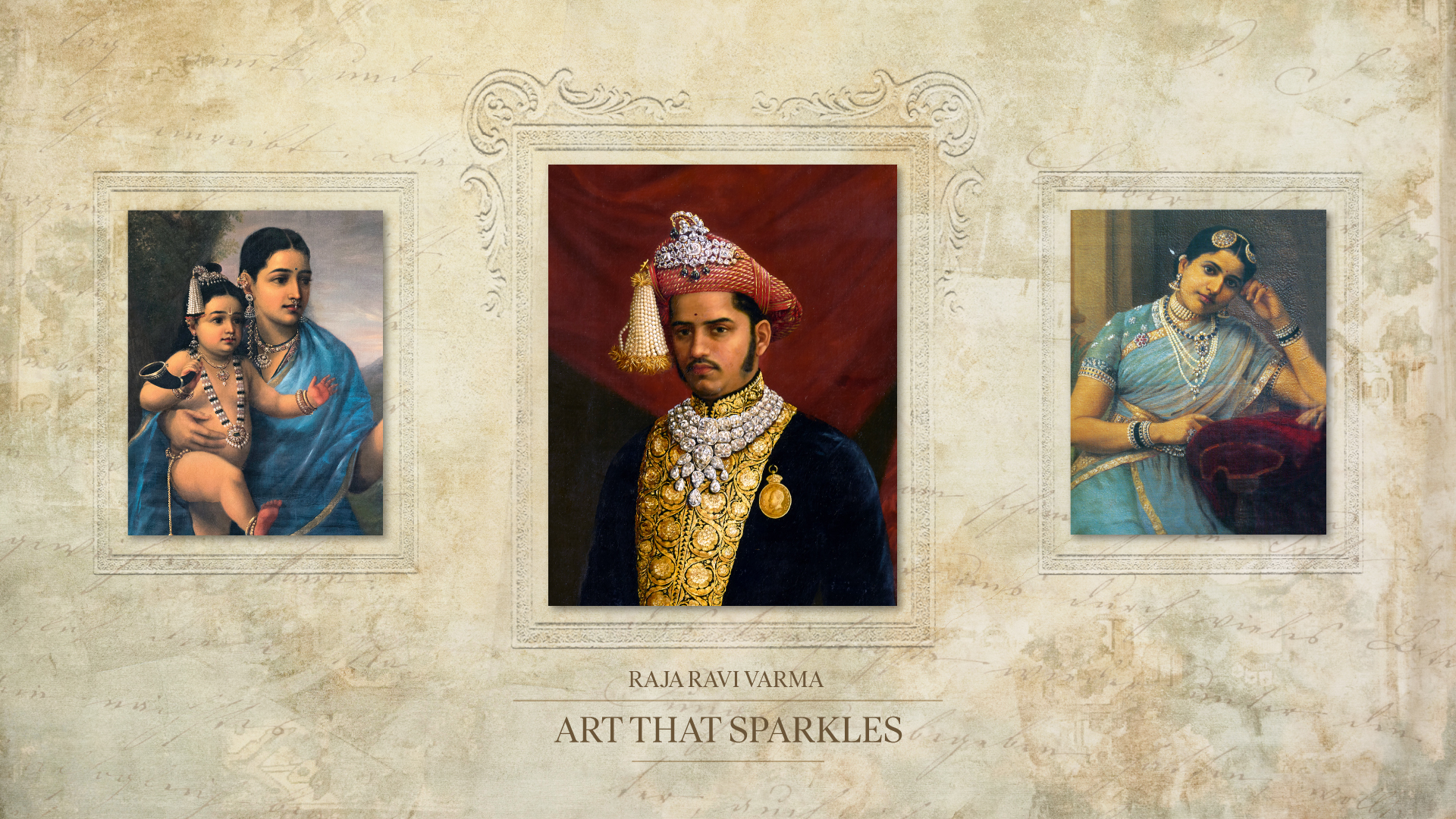

Even before he turned 22, Varma had mastered the distinct style he would come to be known for. Some of his favourite themes were from Indian mythology, and this 1870 painting of Yashodha pointing out cows to a young lord Krishna was a dramatic shift from how gods and goddesses had been portrayed until then. Not for Varma were the distant, flat, out-of-reach deities of earlier depictions. Instead, he imbued his gods with all the softness and realism of humans. Yashoda and Krishna in this painting could be any mother indulging her child but for the fact that Varma bedecked them with diamonds of the first water. Author and historian Manu Pillai points out that a lot of what Varma painted, especially in the early years, was inspired by jewellery he saw around him in aristocratic circles. When Varma and his brother visited other royal courts, they were often given tours of their treasuries. “It is very possible these experiences moulded their choices when depicting various gods,” Manu adds. With sparkling diamond bangles encircling his chubby wrists, a large diamond pendant hanging from a pearl necklace, and a diamond-studded sarpech on his head, Varma’s Krishna is transformed from adorable to numinous. As befitting the mother of a god, Yashodha too is exalted with diamond earrings, necklaces and a diamond studded bangle.

A Little Prince and the Sparkle of his Jewels

For his more mortal subjects, who were often royals, Varma had a slightly different approach. Having grown up in close proximity to royalty, he understood the significance of jewellery in the royals’ lives, and its importance in such portraits. “He would ask that his royal sitters put on the actual jewels they wished to be portrayed wearing,” Jay Varma explains. In 1879, Varma was invited to the principality of Pudukkottai in Tamil Nadu, to paint portraits of its rulers—the Tondaimans. The young Marthanda Bhairava Tondaiman had been adopted by his grandparents as their heir, and Varma’s commission to paint a portrait of the princeling was perhaps meant to be an official recording of his title, as well as its legitimization courtesy the family jewellery he sports.

In the 1882-1886 portrait, Varma captured two contrasting aspects of his model: his raw innocence, and the unmatched sparkle of the jewels he wore as the young prince of Pudukkottai. Marthanda was under ten years old when this portrait was painted, but in keeping with his status, rows of diamonds decorate his headgear, two massive diamond-and-ruby pendants hang down his chest, and his still-soft hands are weighed down by chunky diamond-and-ruby studded bracelets.

Diamonds & Divinity

In 1881, at the age of 33, Varma was invited to Baroda by Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III. The invitation was to lead to some of his most significant works, both in terms of style and content. Varma’s Baroda-era paintings of Lakshmi and Saraswati introduced a realism to their depictions that were so impactful, they replaced the traditional religious iconography associated with these goddesses. In popular consciousness henceforth, when these goddesses were invoked, their imagery—in prints, posters and idols—was rooted in Varma’s paintings. But the seed of this most prolific period was sown by an 1880 painting titled Sita Bhumi Pravesh. The painting—a scene from the Ramayana—captures the hurt and anguish of Sita, who, after being rejected by her husband Rama, the king of Ayodhya, returns to her mythical mother, the earth. Varma outfitted all the characters in this painting with accoutrements of their stations and states of mind. The sages wear no jewellery; Sita’s sons, the simplest of gold ornaments; Lakshman wears pearls and a crown; but Rama, as the king, wears diamonds—they sparkle imperiously in his towering Tanjore-style crown, his armbands, his armour, bracelets and rings. “There is more jewellery here than is typically seen in Ravi Verma paintings,” says Radhikaraje Gaekwad, the titular Maharani of Baroda, adding: “The jewellery and diamonds in the painting are because that was Varma’s envisioning of the zenith of Rama’s rule—the Rama Rajya and all that it stood for.” It is interesting to note that despite being a queen, Sita wears no crown in this painting. “The imagery of wealth is being displayed in that picture, and she [Sita] is actually walking away from all of it when she returns to the earth,” Radhikaraje points out. Sita’s only significant jewels in this scene are the diamond-studded bangles that match exactly with her mother’s. It is a poignant detail that only someone deeply familiar with the heritage and symbolism of Indian jewellery traditions would have thought to add.

Sita Bhumi Pravesh was presented to Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III as an emerging artist’s portfolio, and it led to Varma being tasked with painting a portrait of the Maharaja at his investiture. The Baroda court’s reasons to have this portrait painted could have been many: to decorate the walls of the massive Lukshmi Vilas Palace, commissioned just a year before; or to assert Sayajirao’s rights and status even though he had been selected by the British to ascend the throne of Baroda. Ganesh Shivaswamy, a lawyer, scholar and long-time collector of Raja Ravi Varma oleographs, points out that Varma’s commissioned portraits are also worth exploring as statements of power. “The jewels contributed to enhancing that ‘punch’, especially in British India,” he notes.

The portrait of Sayajirao at his investiture is a vivid documentation of some of the world’s most epic natural diamonds—from the sparkling sarpech in the young Maharaja’s turban, to the Akbar Shah and Star of the South diamonds in the dazzling three-tiered necklace around his neck. Aside from their actual value, these natural diamonds carried the legacy of a rich imperial heritage. “The diamonds were extremely important because of their history and ancestry,” says Radhikaraje, adding, “And the coming together of these pieces of power and proclamations of prosperity around the neck of the new monarch of Baroda was really announcing the arrival of the new face and future of the state.”

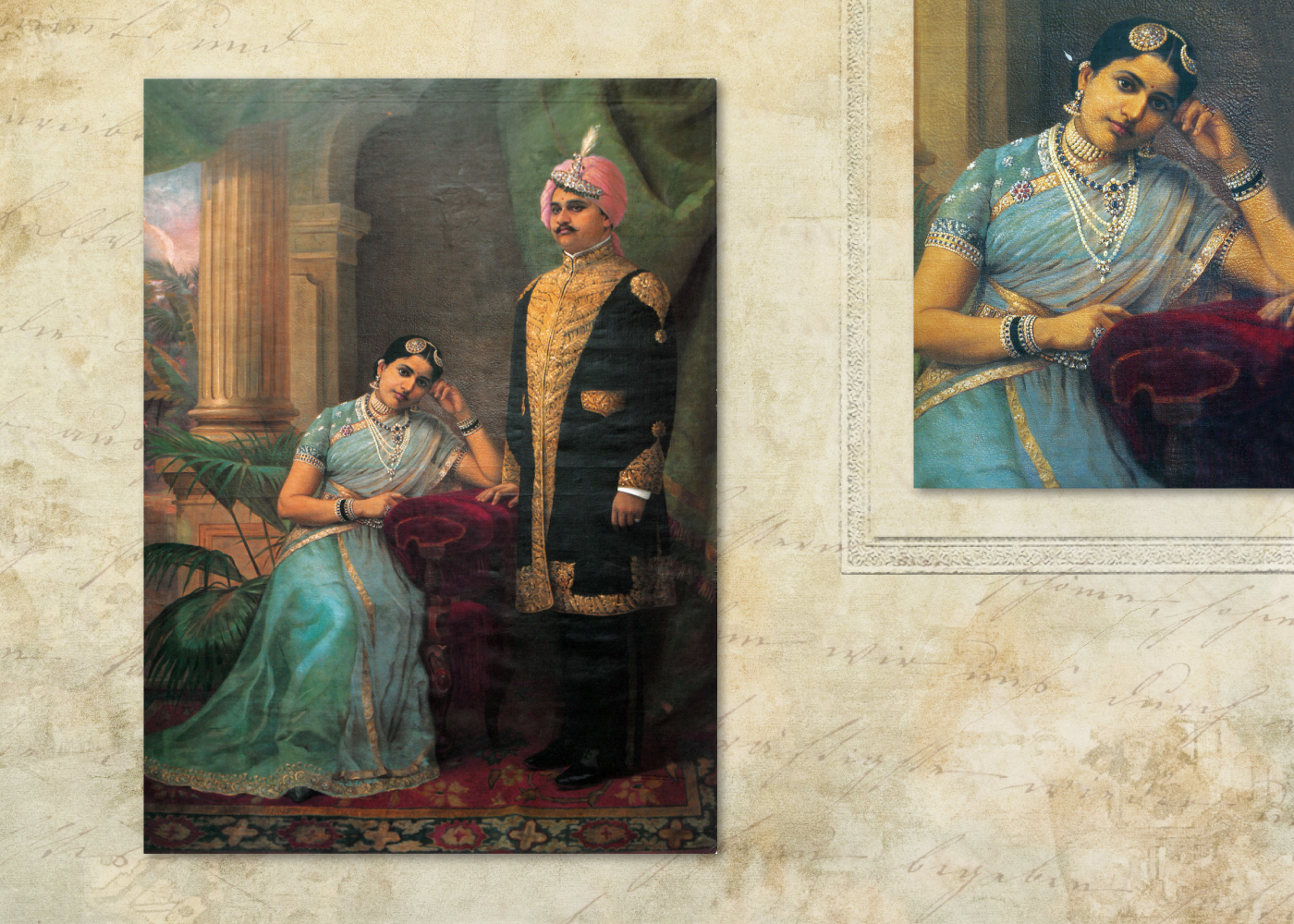

Explore the Beauty of the Rani of Kurupam’s Diamond-Studded Painting

In 1902, Varma was tasked with an unusual commission by the recently widowed and bereaved Raja of Kurupam: to paint a portrait of him and his beloved wife. Though his practice of asking his sitters to wear their jewellery was not possible in this case, Varma and his brother used photographs of the young Rani and created an image of her imbued with softness and light. Perhaps empathising with the Raja’s grief (for Varma too had lost his wife a decade before), the Rani of the portrait seems almost ethereal. Her diaphanous blue dupatta is offset by pearls, sapphires and of course the diamonds that encircle her neck, wrists, waist and fingers, and seem to distil starlight into her earrings and hair ornaments. The popularity of this particular painting seems to transcend time and in 2020, it was recreated by filmmaker Suhasini Maniratnam for a calendar, and featured actress Shruti Hasan, as the sweet-faced Rani of Kurupam.

Varma’s models all seem to step from the past, radiant with timeless grace. It is rare to see art that resonates with people ages after its making, but in Varma’s paintings you begin to understand why—because it lets viewers escape, for a short while, into a world of gentle beauty and soft light. Like all art, Varma’s was imprinted with layers of the personal and political. Like diamonds, it is opulent, authentic and inimitable.