From Golconda to Persia: The Legend of The Great Table Diamond

When Nader Shah rode away from Delhi with his caravan of loot, he had in his possession the largest pink natural diamond in the world. Here’s the story of what happened to the gorgeous gem in the centuries that followed.

Illustrations by Shawn D’souza; Photograph of Nadir Shah by Alamy

|

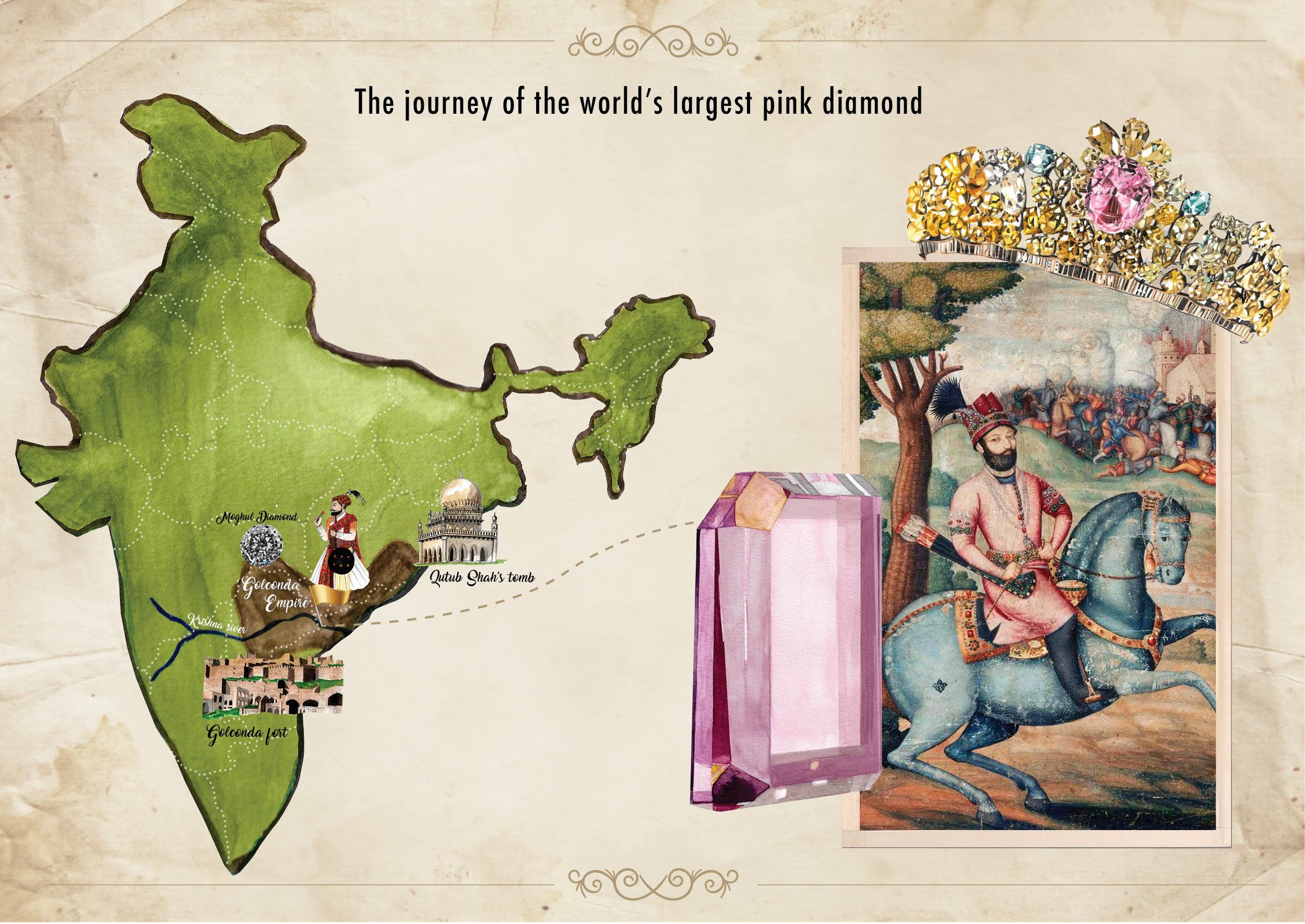

The diamonds that were coaxed out of the muddy depths of Golconda cannot just be valued in terms of carat, cut, clarity and colour. Coveted by emperors, queens, tsars and shahs, almost every rock from here is drenched in legend and lore. In this series on the Golconda diamonds, we trace the story of the world’s largest pink diamond, the Great Table and where it is today.

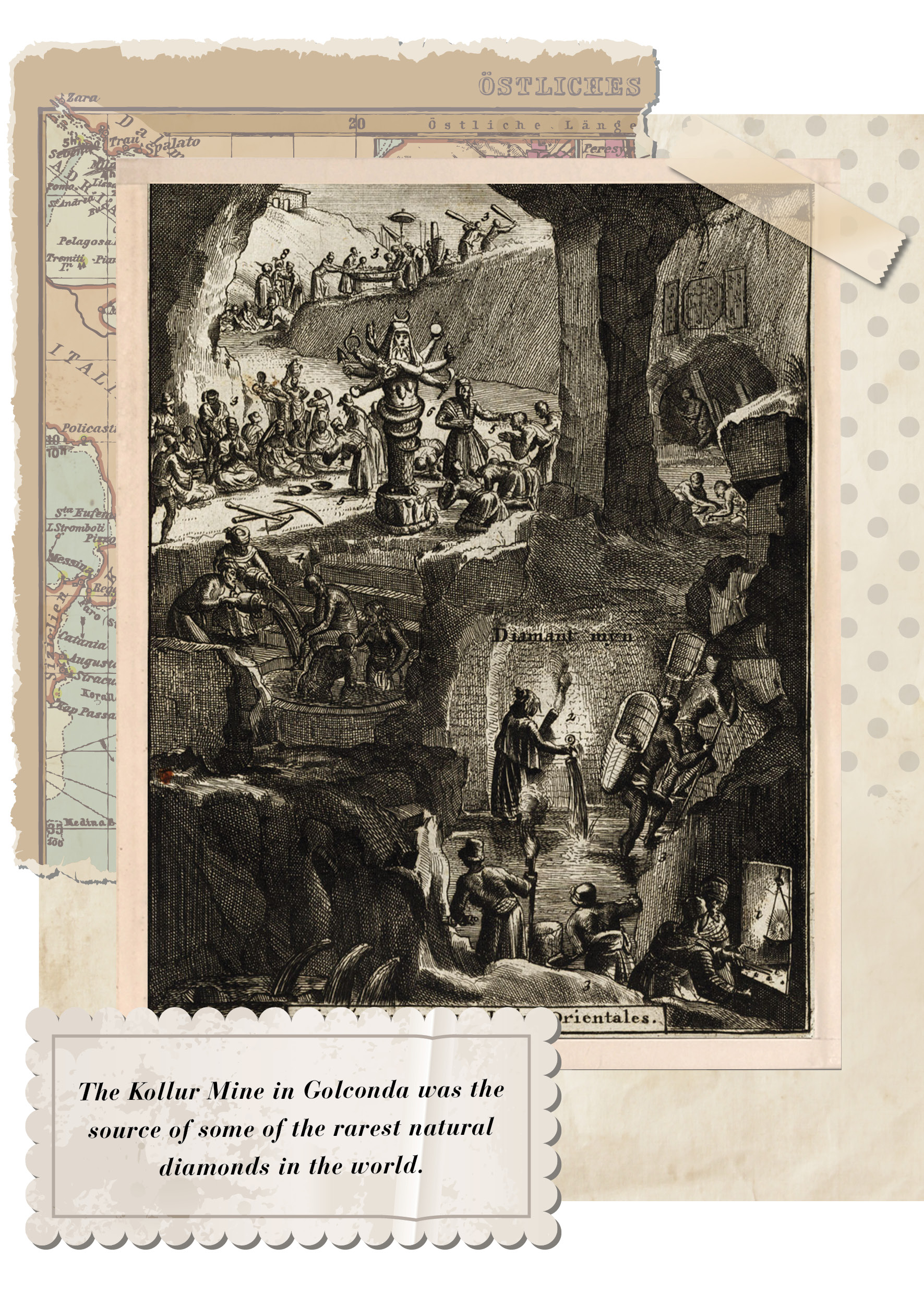

On one of the several trips he made to India in the 17th Century, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a jeweller and a traveller, came across something that took his breath away. This was a man who knew gems and diamonds, often procuring them for the French crown, and he was fully aware of the treasures the Kollur Mine was capable of producing. But even then the rare, natural pink gem he saw on his trip to this part of the world in 1642 left him so awestruck that he couldn’t even fathom an evocative and elegant-sounding name for it. Alongside the notes that he jotted down in his diary, he sketched a photograph of the massive, brilliant rock that he called the “Diamanta Grande Table” or Great Table Diamond.

The name was a reference to the table-cut of the rectangular stone that had one of its corners faceted off, making it instantly recognisable. And great, well that was a reference to its immense size – it had to have been more than 250ct.

The Great Table Diamond, the largest and clearest pink diamond in the world, like most other famed Golconda gems, came from the pits of the Kollur Mine. Located on the southern banks of the Krishna River in Golconda Sultanate of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, today this area is part of the modern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. In addition to the Kollur Mine, this area was home to 22 other such pits that together produced the bulk of the world’s diamonds from the 16th till the 19th Century. But it wasn’t just the volume of diamonds this area was known for. These rocks were believed to be of unparalleled quality, clarity and size. No wonder the fabled Golconda diamonds were hugely desirable and went on to adorn the crowns of many of the wealthiest monarchs in India and around the world.

Just like many other Golconda diamonds, the Great Table Diamond was passed from kingdom to kingdom, from the Golconda Sultanate to the Delhi Sultanate, eventually coming to jewel the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan’s Peacock Throne in the Diwan-i-Khas chamber of the Red Fort in Delhi.

Here it sparkled alongside other Golconda diamonds including the Koh-i-Noor, the Akbar Shah and the Great Mughal Diamond, all of which adorned this very literal and visible seat of Mughal power in India.

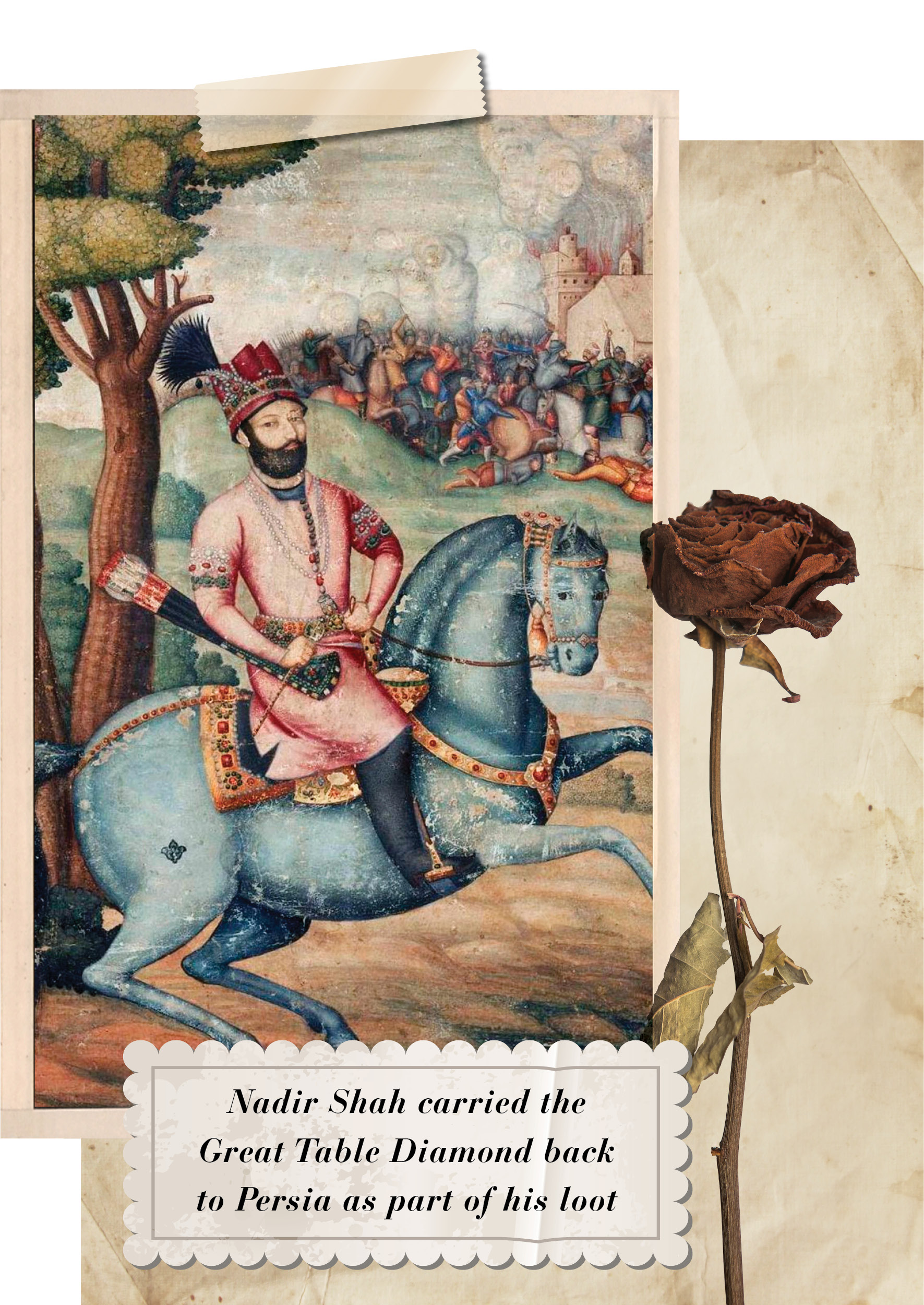

But by the early 18th Century Mughal power was on the wane. So when in 1739 the Persian ruler Nader Shah attacked from the north, sacking and decimating Delhi, Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah had no option but to surrender most of his riches just to get the invaders to leave the city. The treasures he gave up included the Peacock Throne and all of its magnificent jewels, including the Great Table Diamond.

However, the magnificent stone wasn’t to be Nader Shah’s for long. When he was assassinated only a few years later, it is reported to have been passed down to his grandson Shahrokh. Again, the Great Table Diamond passed hands and dynasties, a talisman keenly coveted by whoever sat on the throne of Persia. But it was rarely seen outside royal circles. When the diamond was last spotted in 1791 by Sir Harford Brydges, a British diplomat in the region, it was only because the then Shah had recruited his services to try and sell some of his gems to fund militaristic designs on one of his neighbouring kingdoms. After that, it was as if the magnificent rock simply vanished.

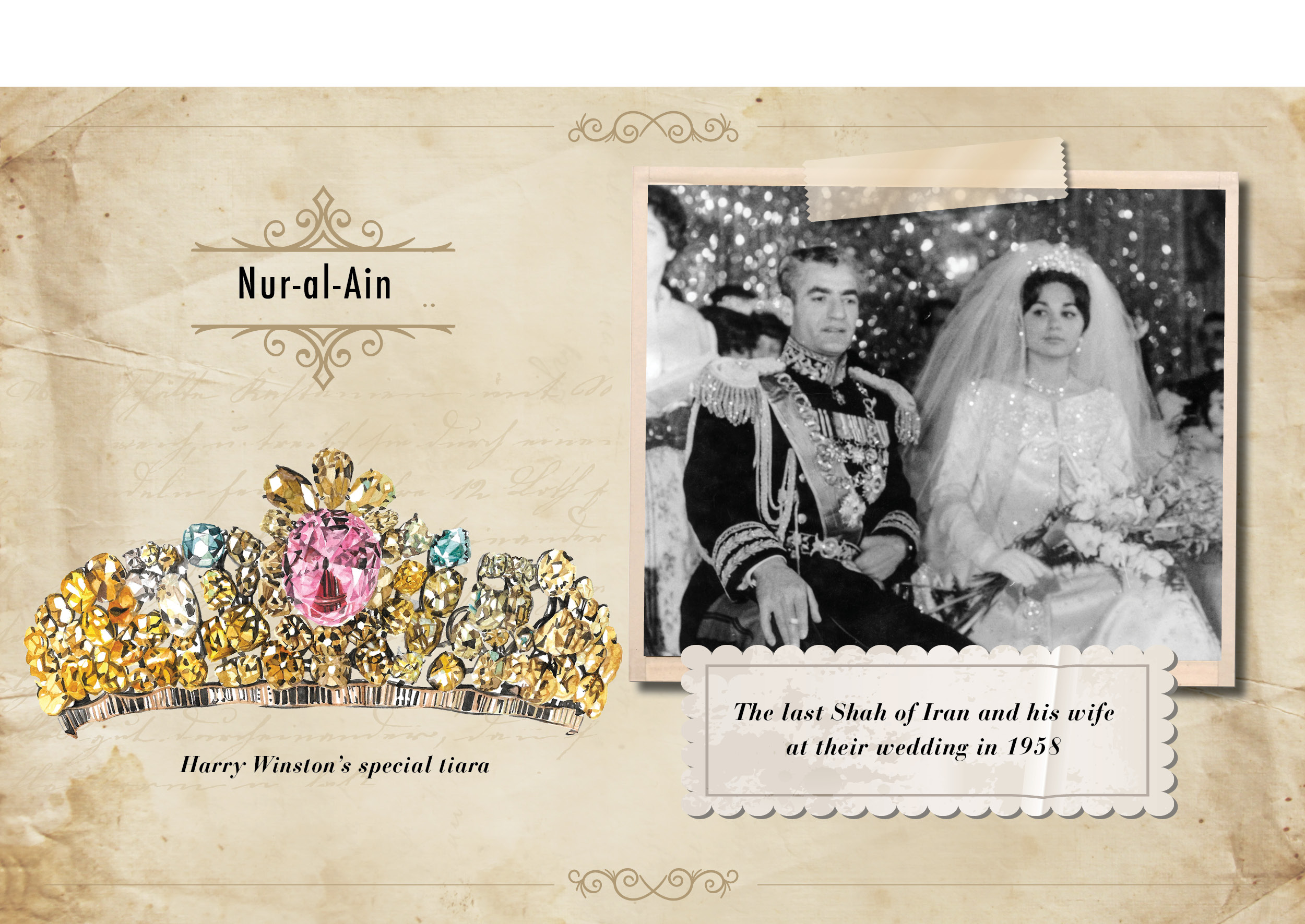

The mystery of the whereabouts of the Great Table Diamond was reignited when successive Shahs of Iran started appearing in public wearing a magnificent pink diamond, considerably smaller in size than the Great Table Diamond, but remarkably similar in colour and clarity. In fact, Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, Shah of Iran in the late 19th Century and a keen collector of gems, was regularly seen wearing the smaller rock in his armband, aigrette or as a brooch and was said to absolutely adore it. By the time Reza Shah was crowned Shah in 1926, the mysterious pink rock had taken pride of place in his ceremonial headgear, officially making its way into the Iranian crown jewels. He passed it down as a precious heirloom because the rock made an appearance again when Reza Shah Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran married his third wife. He not only wore the pink stone in his crown, but, as the ultimate symbol of love, during the ceremony he placed a stunning tiara with a matching gorgeous pink stone at the centre, on his beautiful new bride Farah Pahlavi’s head. It was a positively regal take on the traditional diamond engagement ring. But could these be from the famed Great Table Diamond that was thought to have been lost to history?

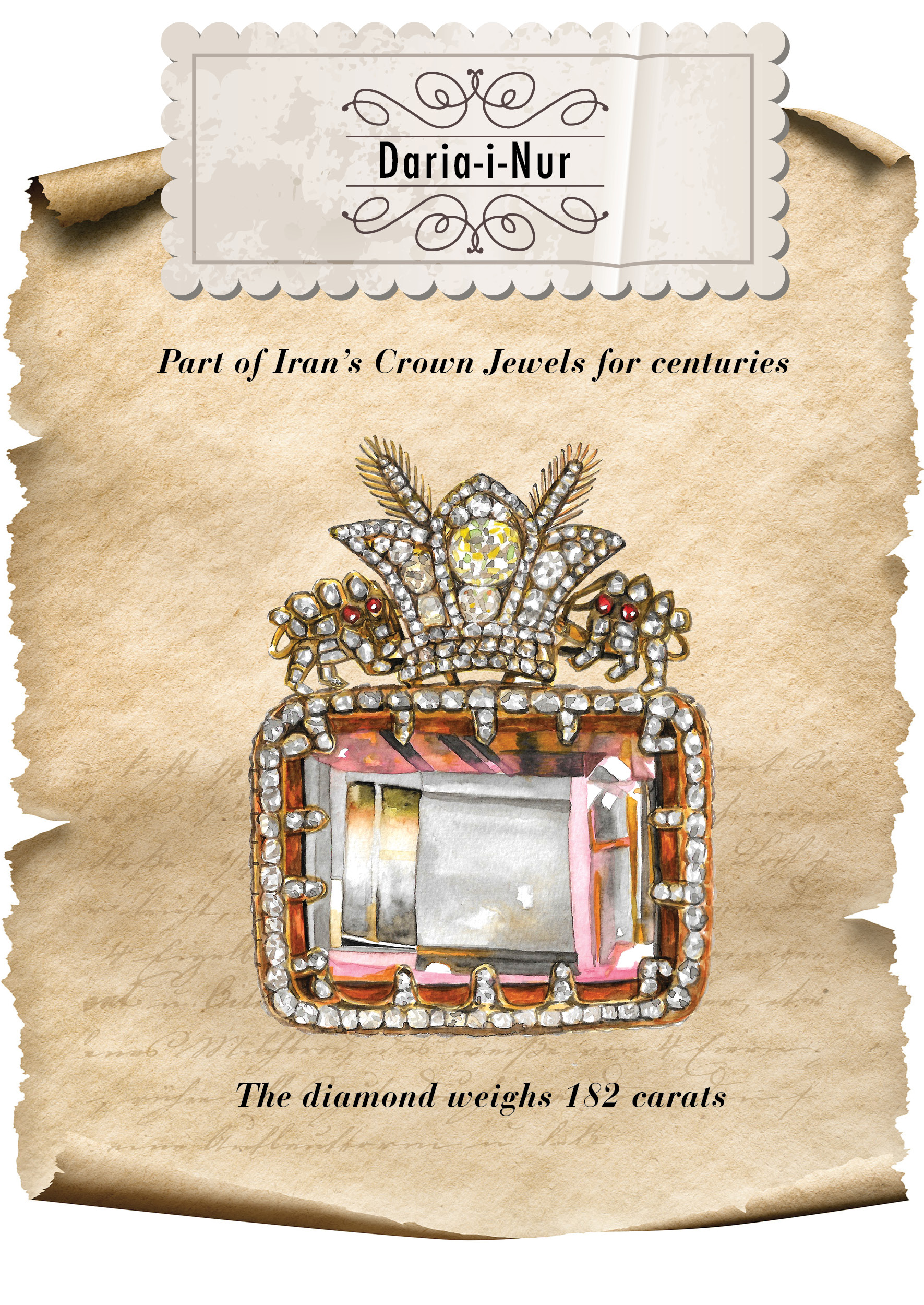

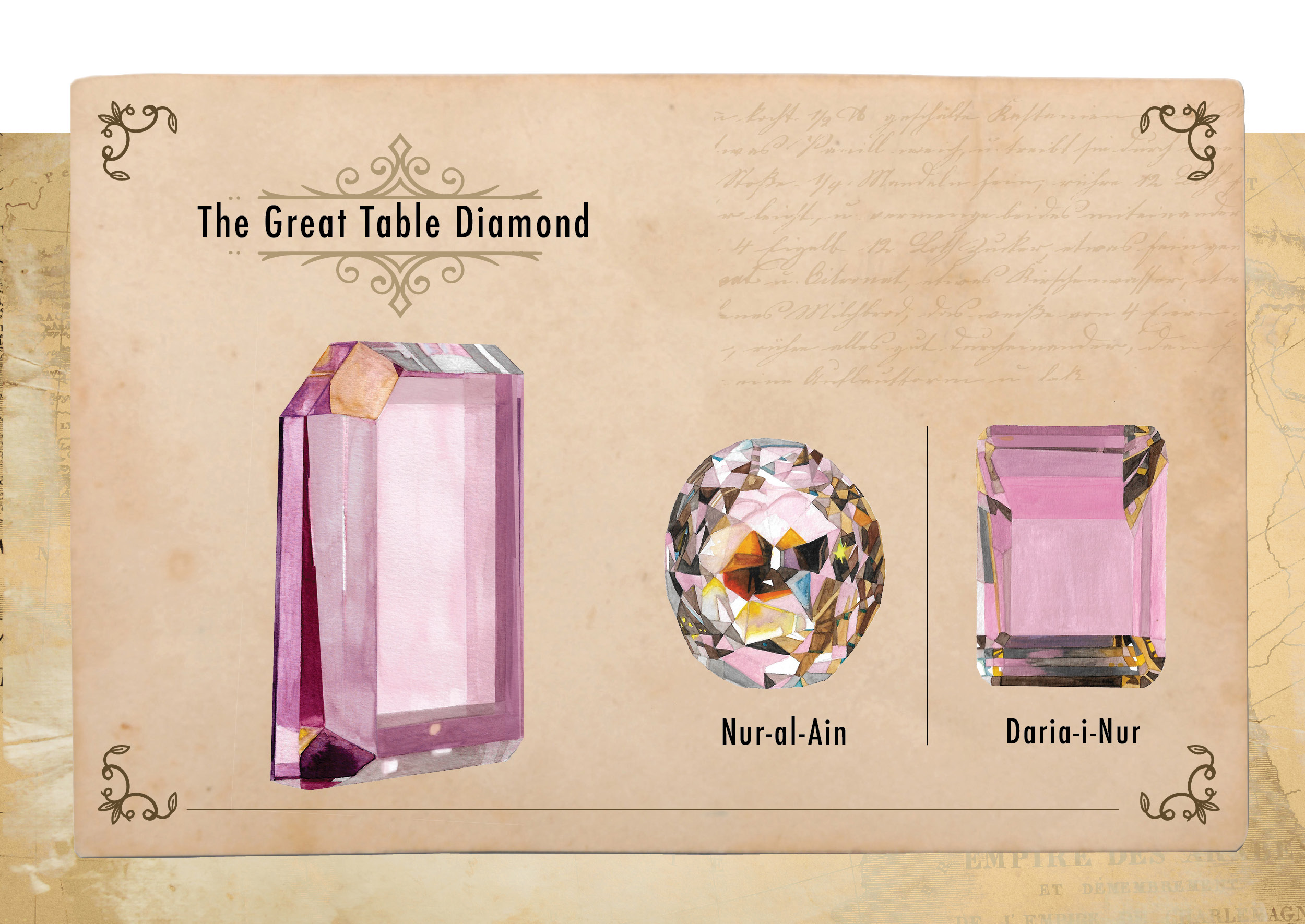

The question wouldn’t be answered definitively till 1969 when a group of Canadian researchers were given unprecedented access to the Iranian crown jewels. They focussed their attention on two stones, known in the royal household as the Daria-i-Nur (sea of light) and the Nur-al-Ain (light of the eye). The former, weighing around 182ct, was the same one that had been worn by successive rulers of Iran since Nader Shah. The latter had been set into a new tiara (also called Nur-al-Ain) specially designed by jeweller Harry Winston as the most romantic token of the Shah’s affections for his new wife on the occasion of their wedding in 1958. This diamond weighed around 60ct.

The evidence all pointed to the same conclusion. The weight of the two stones added up and there was no denying that the colour and absolute flawlessness of both were exactly the same as that of the fabled Great Table Diamond.

It led the researchers to believe that towards the end of the 18th Century the Great Table Diamond had been split in two, the cubic stone going on to be known as the Daria-i-Nur while the facted end was fashioned into the dodecahedral-shaped Nur-al-Ain. When they laid the two stones down flat side-by-side, they could almost see their ends matching up. The age-old mystery had finally been solved.

Far from their home in Golconda, the gems today rest, as stunning as ever, at the Treasury of National Jewels inside the Central Bank of Iran in Tehran, open to visitors hoping to catch a glimpse of this unbelievable treasure. They sit there, the sum parts of the Great Table Diamond, having outlasted monarchs and invaders, royal lovers who gave them as gifts, terrible upheaval and bloody revolution. And yet you wouldn’t know from looking at them. They seem to have endured the centuries with such easy grace. Hardly a surprise though. After all they say, diamonds are forever.

Voiced by Sobhita Dhulipala and visualised by Gaurav Ogale (Patrani Macchi) | Music Credits: © Relaxdaily: Particles of Life by Michael Fesser | Pines // Wild Axe by Zachary Corsa