The Ruler’s Rock

Enthralling rulers and subjects alike since centuries unknown, the natural diamond remains a raison d’etre for many of its paramours.

As Franz Winterhalter stood painting a portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh, there was sudden hubbub and the door opened. Queen Victoria glided into the room. “Maharajah, I have something to show you!” The young Duleep Singh, garbed in exotic silks and the few gems that were left to him, stepped swiftly down from his dais, and, before he knew what was happening, found himself once more in the company of a legend.

The Koh-i-nur. The Queen of England was curious to find out if the erstwhile owner of the grand natural diamond thought it had a better sheen since its new cut and polish. Albeit its size reduced to half. Just one of many stories of natural diamonds, the incident endorses that the lore of diamonds take no hiatus. Legends, stories, wars and coronations have found themselves wrapped in the burnishing glory of diamonds.

A shared awe and connection for this dazzling icy element, the natural diamond seams together destinies of the likes of Bikramjit, the Raja of Gwalior to Emperor Babur, Duc d’Orléans, Regent of France, Napoleon and Nadir Shah and Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the British Royal Family among many others.

A dew drop like pristine natural stone for which wars were waged and spectacles of coronations conducted, the Natural diamond is unlike any of its compatriots. None rest on a pedestal as elevated and revered.

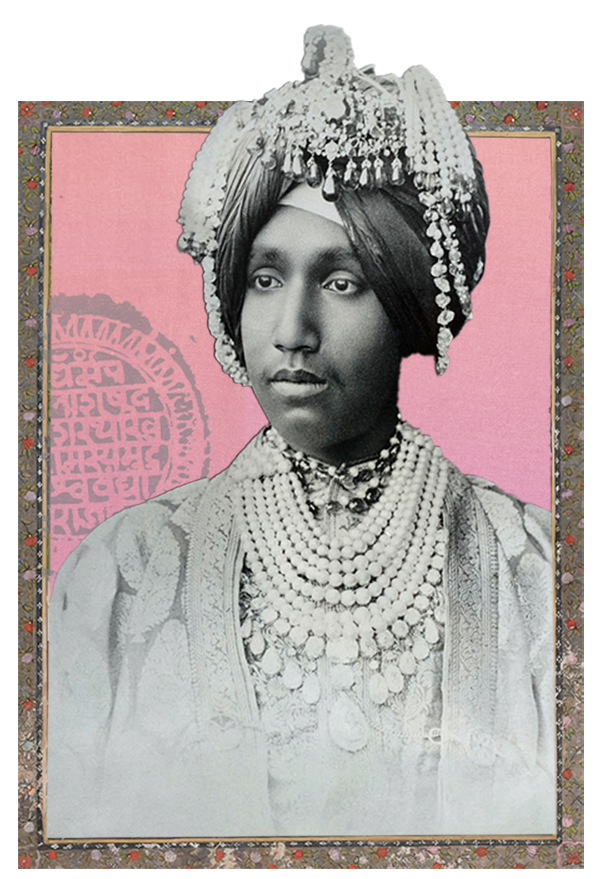

Crowns, and coronations (in the Western style per se) as a symbol of kingship, were not usually associated with rulers in India. Mostly a grand mix of religion and rebellion, the pomp and pageantry were often the aftermath of the coronation when the ruler wielded absolute power. The crown was often the pagri (a silken turban) flanked with a diamond sarpech and bazubands, invested in cosmic ceremonies, apotheosizing divine and celestial ambassadorship in the ruler.

Considered as shields against the toxic eye, it is therefore no surprise that diamonds became powerful symbols. Kings, aristocrats and Emperors bestowed upon themselves these powerful ciphers which Plato believed to embody celestial spirits. And while Plato lived between 427-347 BCE, diamonds unremitting spell never wore off. In 2011, years after Jaipur became an Indian state, Padmanabh Singh became the titular Maharaja of Jaipur at the minor age of twelve. Clad in the colour of moon in a white achkan, the young Padmanabh glistened in a celestial looking diamond Sarpech. Reminiscent of the legacy of erstwhile rulers of Jaipur and diamonds alike.

In 1562, Mary Queen of Scots sent a heart-shaped diamond in a ring to Queen Elizabeth, as a symbol of friendship. The Romans wore diamonds to be invincible in battle. From the scepter of Catherine the Great to the bazuband of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the brilliance and tenacity of natural diamonds has often sparkled in the company of its wearers through the ages.

In 1840, August Schoefft arrived in Lahore. Lahore by then had plunged into an acrimonious internecine cold war among Ranjit Singh’s heirs. Sitting on the golden throne of Lahore was Maharaja Sher Singh who commissioned a portrait from Schoefft. As Schoefft sat to paint his royal subject, his fabulous silks and jewels on the Panjabi Maharaja clamoured to make a statement. From the vaults of the Sikh Darbar the Maharaja dawned gems that transcended centuries and eluded many empires. But what stood out both in Schoefft’s art and story were the burnishing accoutrements on the Maharaja’s arms. On Sher Singh’s right arm was his armlet (bazuband) enshrining the mountain of light, the Koh-i-nur, while on his left arm was another natural diamond, the ocean of Light, the Darya-e-nur. Cyphers and Signals of battles won, great good luck and kingship. Nothing gave impetus like the diamond.

Harry Potter introduced the world of young adults to a sorcerer’s stone, a legendary substance with astonishing powers. But in the world of gems, the sorcerer’s stone is always a natural diamond.

The arrival of the 10th century saw the diamond embedded in the crowns of European royalty. With the opening of trade routes, the diamond lit the dark coffers of many Kings. From the necklace of Queen Claude of France, which contained eleven of the fourteen diamonds from the crown Jewels, to Elizabeth I of England who acquired the famous ‘Mirror of Portugal’ diamond for herself, this natural stone became a symbol of supreme sovereignty.

With the era of modern Darbars and the dawn of the 20th century, change seeped into the world of Indian and world royalty. While the First World War saw the extinction of many a royal household, the exit of the British from the shadow of the Himalayas marked another watershed moment. Thrones fell and power changed hands and the old world order was snuffed out. But just like the vast Himalayan ranges which with its grand avalanches remain steadfast, the natural diamond too rules like a majestic emperor with a flair for grandiosity and invincibility.