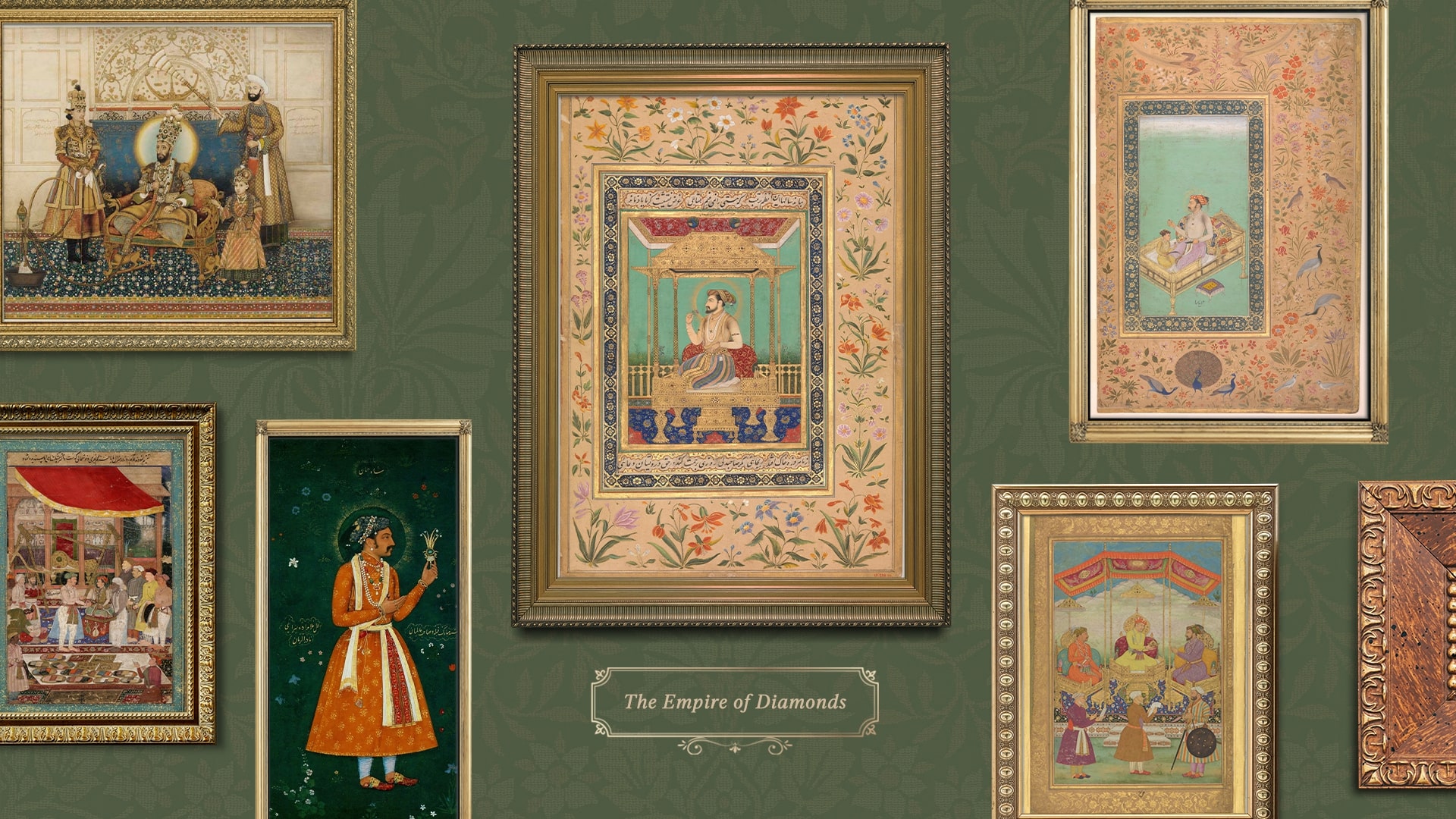

The Empire of Diamonds

Hidden in the dense details of Mughal miniature paintings, diamonds tell the story of an empire—its glorious ascent and its final dénouement.

The year is 1544, and Humayun, whose name means ‘blessed’ or ‘imperial’, is feeling decidedly neither. This son of Babur, after fleeing the armies of Sher Shah Suri across Hindustan, has found himself in Persia, sheltering at the court of Shah Tahmasp. But it is during this exile at the Safavid court that the battle weary and dejected Humayun first comes across magnificently worked manuscripts, and dazzling, precious-gem-studded jewellery, weaponry and artefacts. Having inherited his father’s keen eye and refined aesthetic sensibilities, he is mesmerised, and now determined that his court too—when he has one, that is—will produce objects of beauty as inimitable and elaborate as these. Despite being a landless refugee at the time, Humayun enthusiastically invites two Persian artists to join him in his courts, and in doing so, lays the foundations of the artistic traditions that will both document the empire founded by his father, as well as hold up to it, both mirror and light.

In 1556, Humayun is succeeded by his son Akbar, under whom the Mughal Empire begins to prosper, and with it, the patronage of the arts. Within ten years of his rule, Akbar amasses a collection of 100 artists and craftsmen for his atelier at his newly founded city Fatehpur Sikri, in Agra. Here, within the magnificent red sandstone walls of his new capital, the cultural and aesthetic traditions of Persia, Central Asia and India mix and mingle to create the unparalleled richness of the Mughal style that manifests in literature, music, calligraphy, painting, precious-gem collection and jewellery making.

The Crown Jewels

The hallmarks of the style—vivid colours, intricate craftsmanship and clear, cross-cultural influences—are best seen in the miniature paintings and jewellery of the period. Take, for example, this group portrait of emperors Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan, painted by court artist Bichitr, in Agra. The painting, while ostensibly outlining the significance of succession in the Mughal Empire, also showcases the three rulers under whom the Mughal miniature style of painting truly comes into its own.

The painting’s jewel-like colours, intricate brushwork and richness of material are clear evidence of the value the Mughals’ placed on art—but they also depict the wealth of the Mughal court. All three rulers sit on raised thrones that are gilded and gem-studded. Akbar is the least decorated of the three, and his grandson, Shah Jahan, the most (note his belt, embedded with large table cut diamonds and a central ruby), as befitting one who will inherit an empire. Akbar hands a Timurid crown over to Shah Jahan, and mounted on top of the crown is a unique diamond the size of a pigeon’s egg. While there is no clear documented evidence of this diamond’s history and provenance, this is likely to be the ‘Akbar Shah’ diamond, which Shah Jahan is believed to have had inscribed with his own, his father’s, and his grandfather’s names. Paintings—and prized gemstones—as seen in this miniature, are instrumental in establishing legacy and heritage. An inventory of the royal treasury at the time of Akbar’s death included rare diamonds, emeralds, rubies, sapphires, pearls and other precious gems valued at over 60 million rupees—and this was excluding the gold ornaments

The Mughals’ many treasures have greater significance than just as jewellery or ornamentation, though. Precious stones are symbols of imperial power, strength, resilience, ancestry, and the divine rights of kings. The Mughal emperors are considered (by themselves, at least) as representatives of god on earth, and they make sure to dress the part. When they don their jewels, it is to create a spectacle that will awe their subjects and visitors.

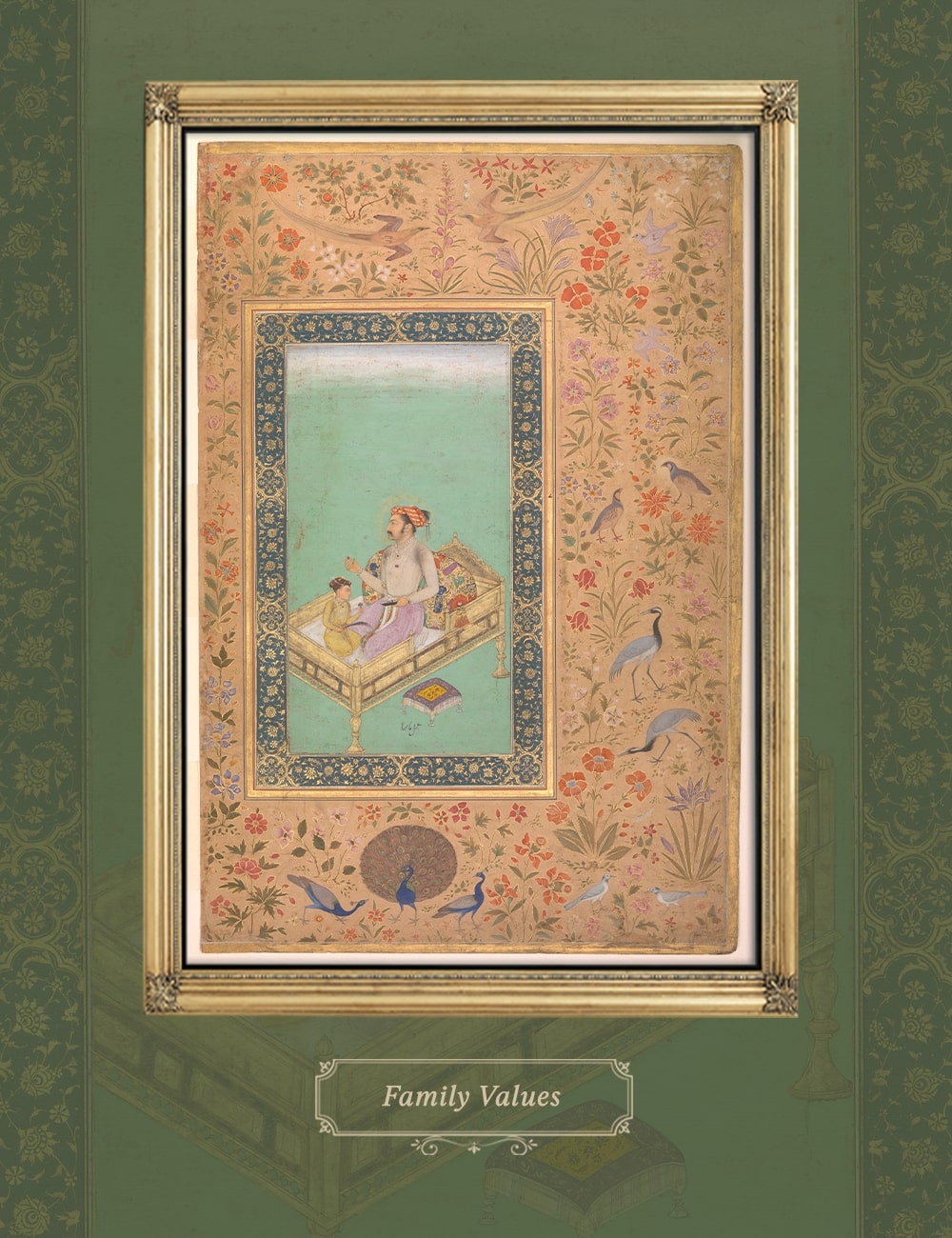

Family Values

But the jewels have a role to play in their daily lives too. In this painting of Shah Jahan with his son Dara Shikoh, court artist Nanha captures both the warmth of the father-son relationship, as well as the importance of jewels in the life of the Mughal royals. The duo is seen here engaged in a particularly royal recreation—examining and appreciating a tray of gemstones. While the tray holds natural, uncut emeralds and rubies—which the Emperors would often have inscribed with their names and lineage—father and son, even on this non-ceremonial occasion, wear ropes of pearls and diamonds interspersed with emeralds and rubies around their necks, wrists and, in Dara Shikoh’s case, his turban too.

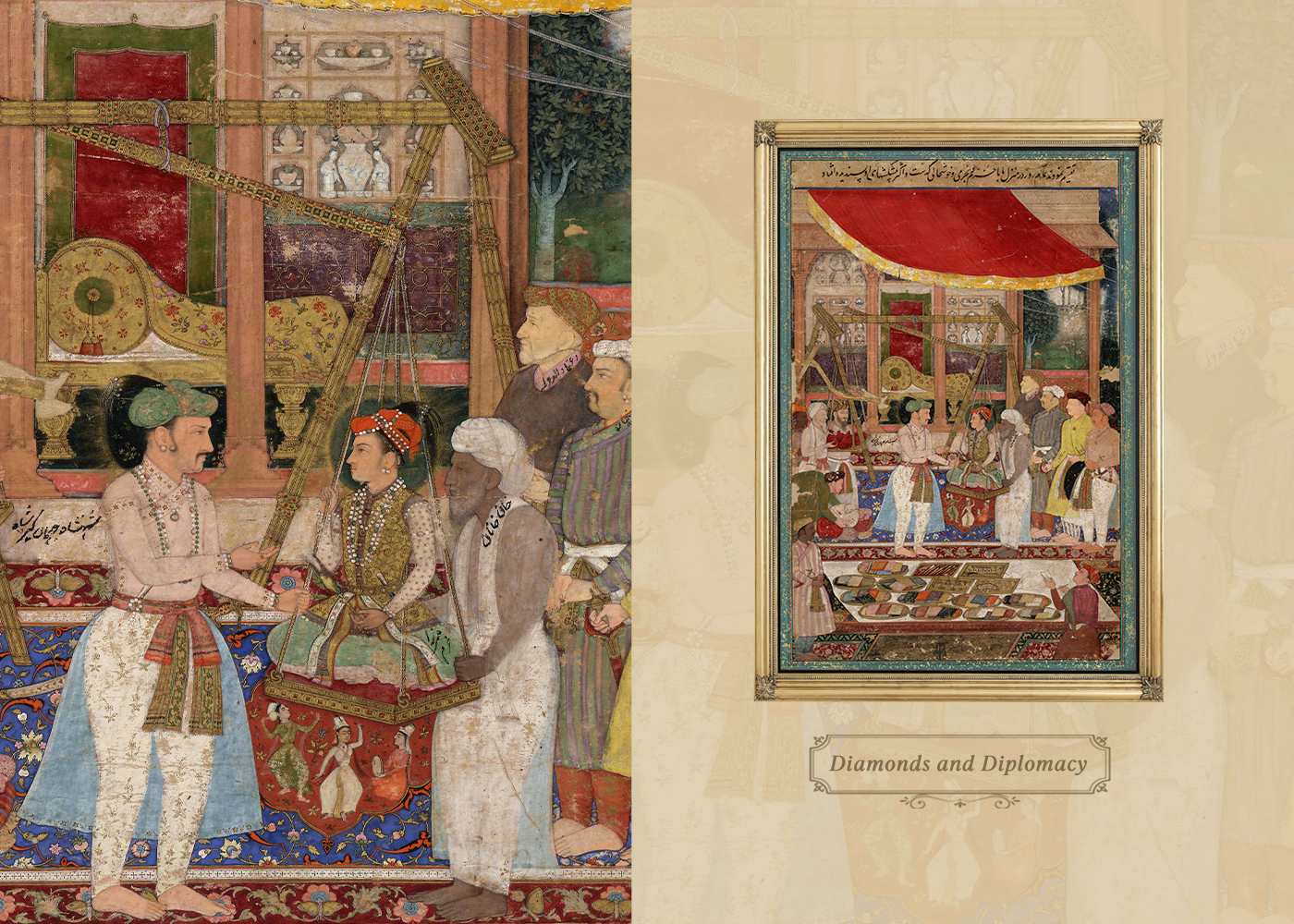

Diamonds and Diplomacy

In Manohar’s painting of Jahangir weighing Prince Khurram, we see yet another example of the role of gems and jewellery in the Mughal Empire. A tradition practised by royals in that period is to weigh members of their family against jewellery, gold and gemstones on ceremonial occasions. The value of the jewellery and gemstones is then distributed among the poor as a gesture of celebration, goodwill and benevolence towards the Empire’s subjects. But the ritual, as well its documentation, is as much a political project as an artistic one. The Mughals are Muslims in a largely Hindu land, and this custom—likely derived from a Hindu one—reflects sulh-i-kul; the belief in peace and tolerance towards all, irrespective of religion, that was brought into practice at the Mughal court by Jahangir’s father, Akbar. ”

Here, Jahangir weighs Prince Khurram, on what is most likely his 15th birthday. Manohar’s detailed documentation of this royal tradition speaks volumes about the gentility of the Mughal rulers, as well as their displays of wealth and opulence—even the scales used to weigh the Prince are gilded and gem-studded.

As befitting a day of celebration, both Jahangir and Prince Khurram wear necklaces of emeralds, pearls and diamonds. While it is almost impossible to definitively identify jewellery set with diamonds in these paintings—given their small size and the rendering techniques used—studies of artefacts and memoirs of the period make it clear that diamonds are very common in the Mughal treasury—in jewellery and in weaponry. Sir Thomas Roe’s description of Jehangir arriving at court reads: “Here attended the nobility, all sitting about on carpets, until the king came, who at last appeared, clothed, or rather laden with diamonds, rubies, pearls and other precious varieties—so great, so glorious.”

In this painting, it is very likely that the rosettes decorating Jahangir’s sash, and the ones fitted on the choker, sarpech and necklaces in the other trays, are all set with diamonds. Jahangir’s and Prince Khurram’s daggers, the daggers in the tray, and the collection of gem studded containers would also have had diamonds embedded in them

Symbols of Sovereignty

Gemstones in the Mughal courts, while valued for their rarity, physical properties and provenance, are also seen as markers of sophistication, strength and authority. In this portrait of Prince Khurram by court artist Abu’l Hasan, the prince is shown holding a turban ornament with an emerald and a massive diamond. The portrait was most likely painted when he was 25 years old, and Jahangir gave him the title ‘Shah Jahan’, meaning ‘King of the World’. While portraits of individuals holding flowers, ornaments, and artefacts are fairly common in the Mughal ateliers, turban ornaments are often heirloom pieces, worn only by the royals, and represent their hereditary right to rule. The emerald in this sarpech hints at divine blessings (since the colour green holds a special significance within Islam); and the diamond is a symbol of royalty, marking Shah Jahan out as clearly above ordinary mortals. The Mughals often use table or rose cuts for their diamonds, and it is a testament to both the stone’s uniqueness and durability, and Abu’l Hasan’s skill, that the table cut natural diamond here can be clearly identified, and thus, traced to where it is today—in Kuwait’s National Museum, as part of the al-Sabah collection, where it is known as the Shah Jahan diamond.

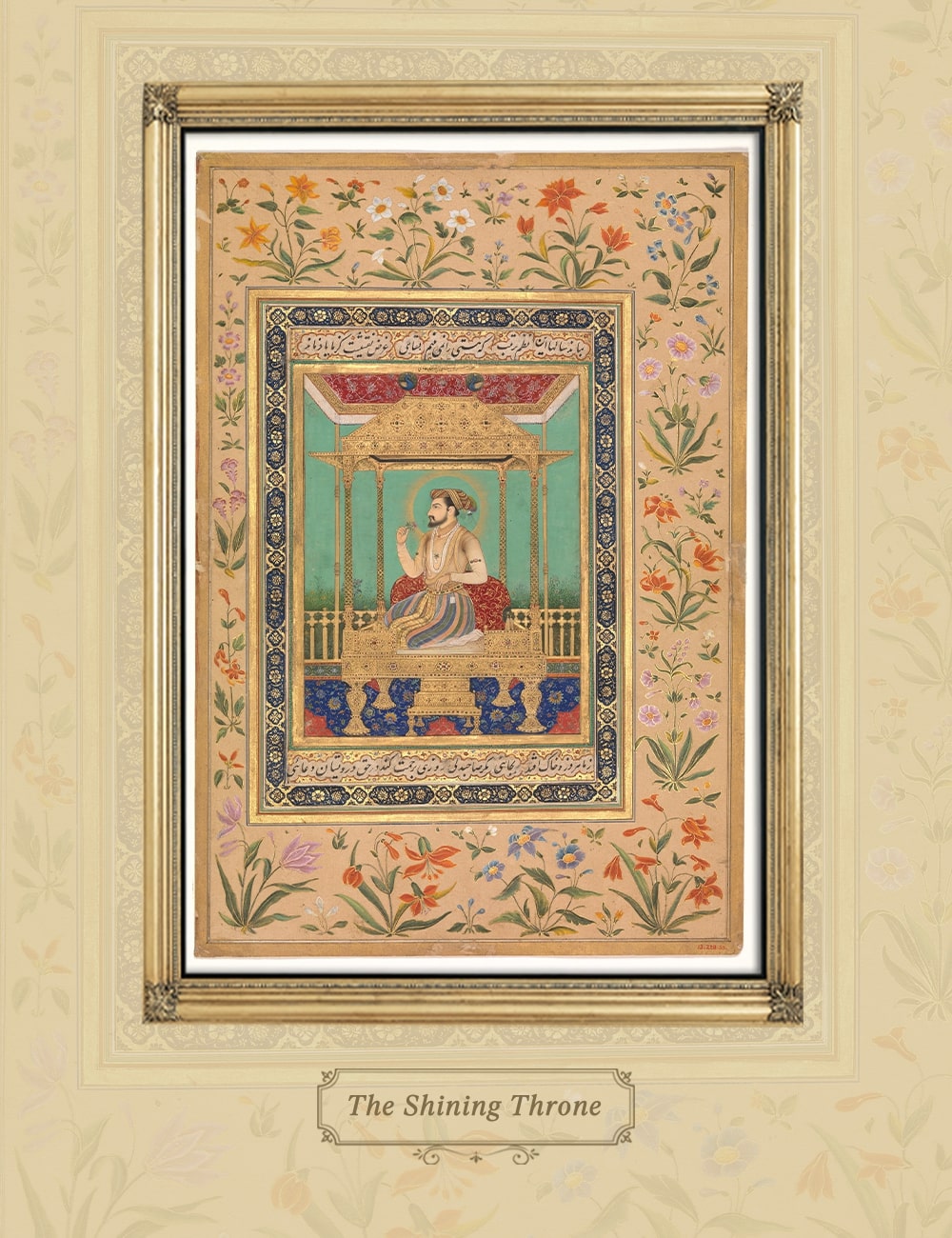

The Shining Throne

But perhaps no other diamond has captured public imagination like the Koh-i-Noor, or the ‘Mountain of Light’. The epic diamond is believed to have been mounted atop the peacock throne that cost, reportedly, two times what the Taj Mahal did. The year is 1628, and Shah Jahan, as the ruler of an empire at its zenith, fancies himself a throne that is, well, fancier than the slab of engraved black basalt used by his father, Jahangir. Surely, the “King of the World” and the “Shadow of God” on earth deserves better than that? With the mythical throne of Solomon as a model, Shah Jahan commissions the most lavish treasure of his empire—the Peacock Throne. The throne, as seen in this painting, uses vast amounts of solid gold, diamonds, rubies, emerald and pearls, and takes a full seven years to complete—but the results are worth it. Seated on it, in state, Shah Jahan looks every inch a ruler appointed by the heavens as he dispenses justice and favours to his subjects.

French traveller François Bernier, arriving at the court of Shah Jahan’s successor, Aurangzeb, notes: “The king appeared seated upon his throne at the end of the great hall in the most magnificent attire. The turban of gold cloth had an aigrette whose base was composed of diamonds of an extraordinary size and value. A necklace of immense pearls suspended from his neck reached his stomach.” And this was a description of Aurangzeb the austere, mind you. Bernier further adds: “The throne was supported by six [massy] feet, said to be of solid gold, sprinkled over with rubies, emeralds and diamonds. I cannot tell you with accuracy the number or value of this vast collection of precious stones, because no person may approach sufficiently near to reckon them, or judge of their water and clearness; but I can assure you that there is a confusion of diamonds.” Bernier’s wonderment is understandable, for, along with the profusion of smaller gemstones, the throne is believed to have held the Koh-i-Noor (considered the world’s biggest diamond at the time), the Akbar Shah diamond, the Jehangir diamond and the Timur ruby.

The Mughal empire, like its most precious diamonds, has been forged under pressure. Its life, however, turns out to be much shorter than its gemstones. Despite being considered a strong emperor, Aurangzeb is a puritan who actively discourages the decorative arts, and by the 18th Century—130 years and 14 Mughal emperors later—in the reign of Bahadur Shah II, the Mughal empire exists largely in name, its ateliers dispersed.

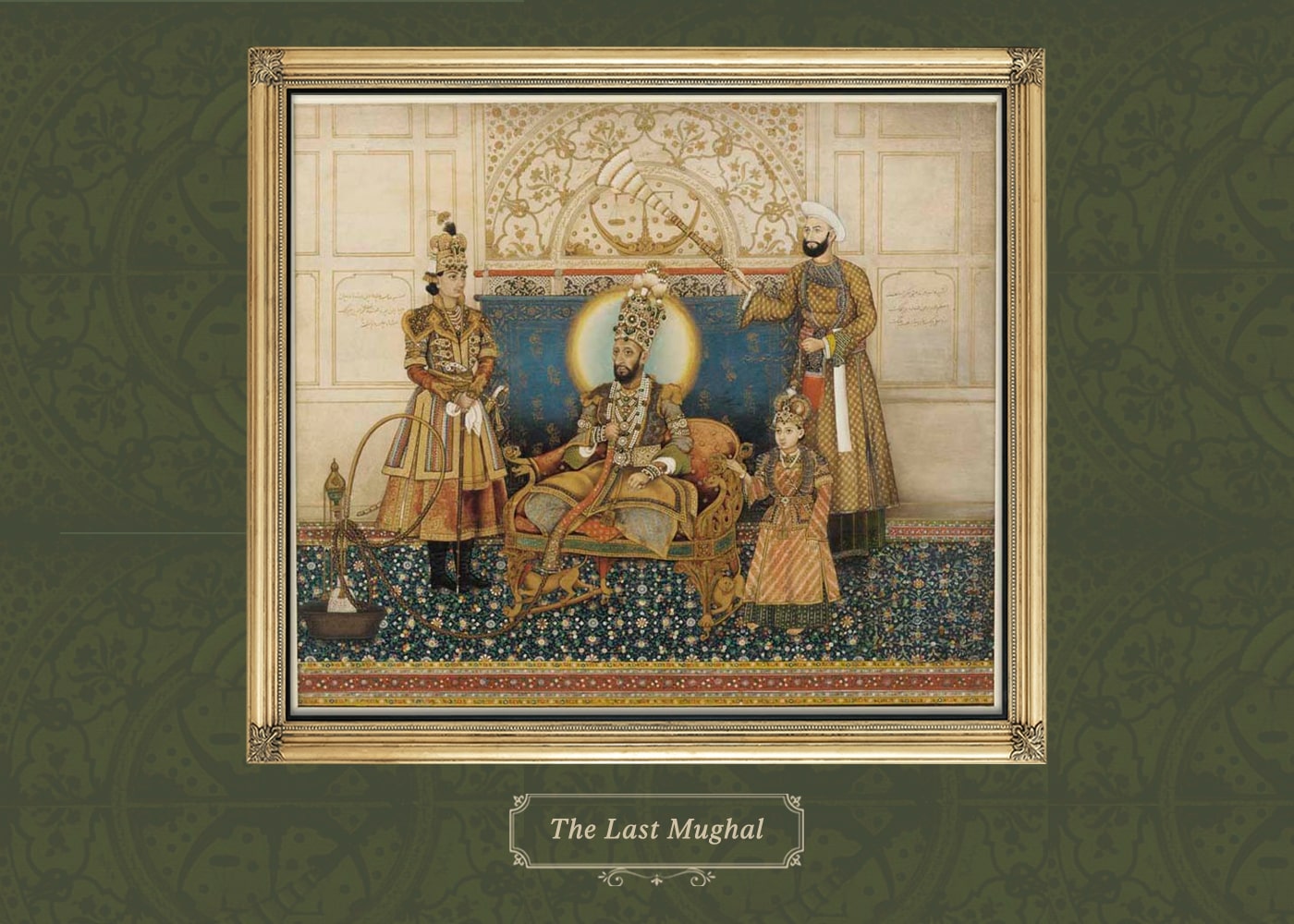

The Last Mughal

But even as he sees the dissolution of the empire his ancestors built, Bahadur Shah Zafar, as seen in this portrait of his ascension, maintains as long as he can, the pomp and grandeur of his dynasty. In this painting by Ghulam Ali Khan—the last of the Mughal court artists—the Emperor’s diamond encrusted turban, necklaces, armbands and belt-ornament speak of the glory of the empire whose rule once stretched from Afghanistan to large parts of the Indian subcontinent. .

Script: Divya Mishra