Tracing The Evolution Of The Hath Phool

Jewellers, experts and royals journey us through the origins, techniques and evolution of this classic gem-encrusted hand harness.

Illustrations by Shawn D’souza

|

It is a well-established fact that traditional jewellery in India is far more than a means of adornment; it is an integral part of our cultural identity. The etymology of ornaments that command popularity today; be it the jhumka, the maang tikka or the nath; can often be traced back several centuries. The hath phool — a form of hand harness that directly translates to ‘flower of the hand’ — is no different.

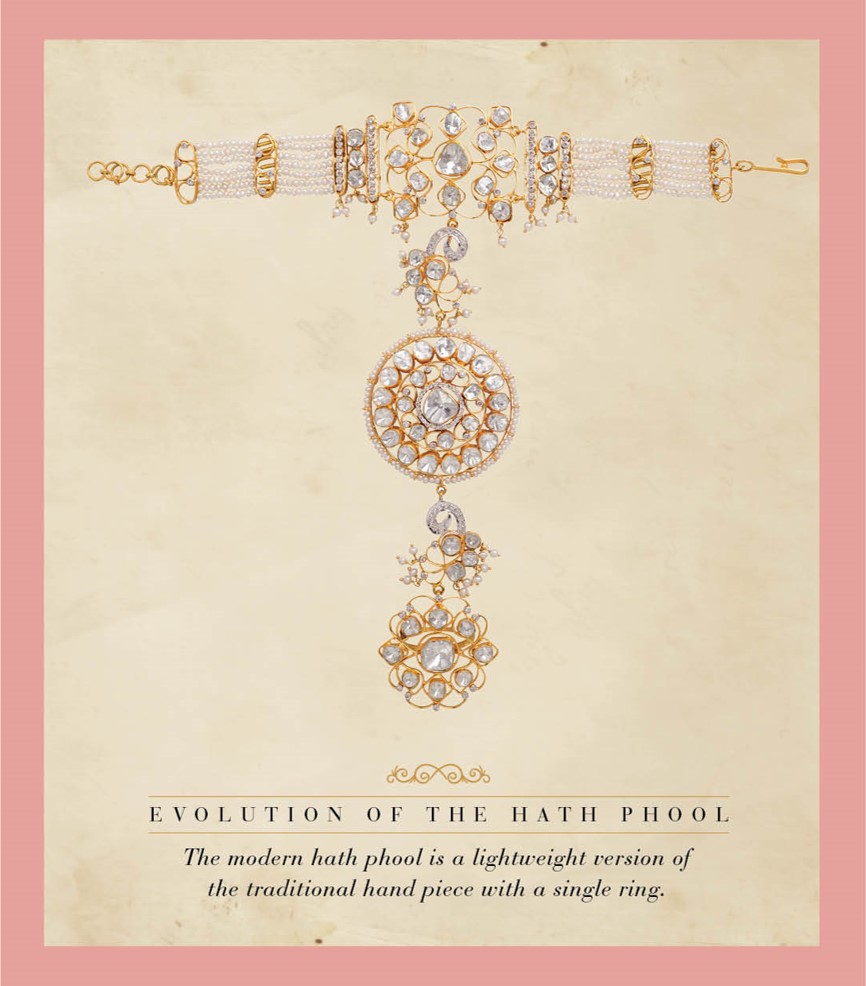

Second-generation jeweller Noelle Van Gelder, whose label Van Gelder Indian Jewellery has been researching traditional Indian heritage jewellery since the 1980s, explains that a quintessential design for the hath phool typically consists of a wrist bracelet which is attached to a circular ornament or medallion resting on the back of the palm (the ‘phool’) by chains or beaded strands. “This is then connected to the five fingers where a mirror ring (arsi) might be attached,” adds her designer sister Fleur Van Gelder.

When a modern jewellery aesthete thinks of the hath phool today, the associations are many — from a free-spirited bohemian sensibility to red carpet-ready glamour. But traditionally, the lineage of this statement-making hand jewellery is one steeped in meticulous craftsmanship — which further evolved as it travelled across the country, and was elevated with various indigenous elements in every region. India’s legacy of celebrating craftsmanship is centuries-old, and these pieces were championed as works of art; using only the finest stones and artistry to create them.

The hath phool’s origins can be attributed to the Mughals, who brought it to the country by way of Persia. “What makes the hath phool so culturally significant is that it is rooted in Asian culture, and was popular across Persia, Caucasia, Russia, Arab countries and even China,” notes author and historian Cynthia Meera Frederick, a specialist on Indian royalty, architecture and traditional jewellery. The hath kamal, or lotus, presented by 12 perfectly symmetrical petals — a hallmark of Mughal design — was one of the most popular designs. As were jaali work typical of Mughal architecture and intricate motifs of chikankari clothing.

The Hath Phool’s Royal Lineage

Not just Mughal queens, but also Mughal courtesans were the first to adopt and popularise the hath phool. It then travelled across the subcontinent, and won the patronage of Rajasthan’s Rajput community. Rajput royalty began to create their own versions, as did the nomads and gypsies of the region. “Hath phools were not restricted to just one community, but were worn by Hindu, Sikh and Muslim women alike, who each interpreted it in their own unique way,” Frederick explains.

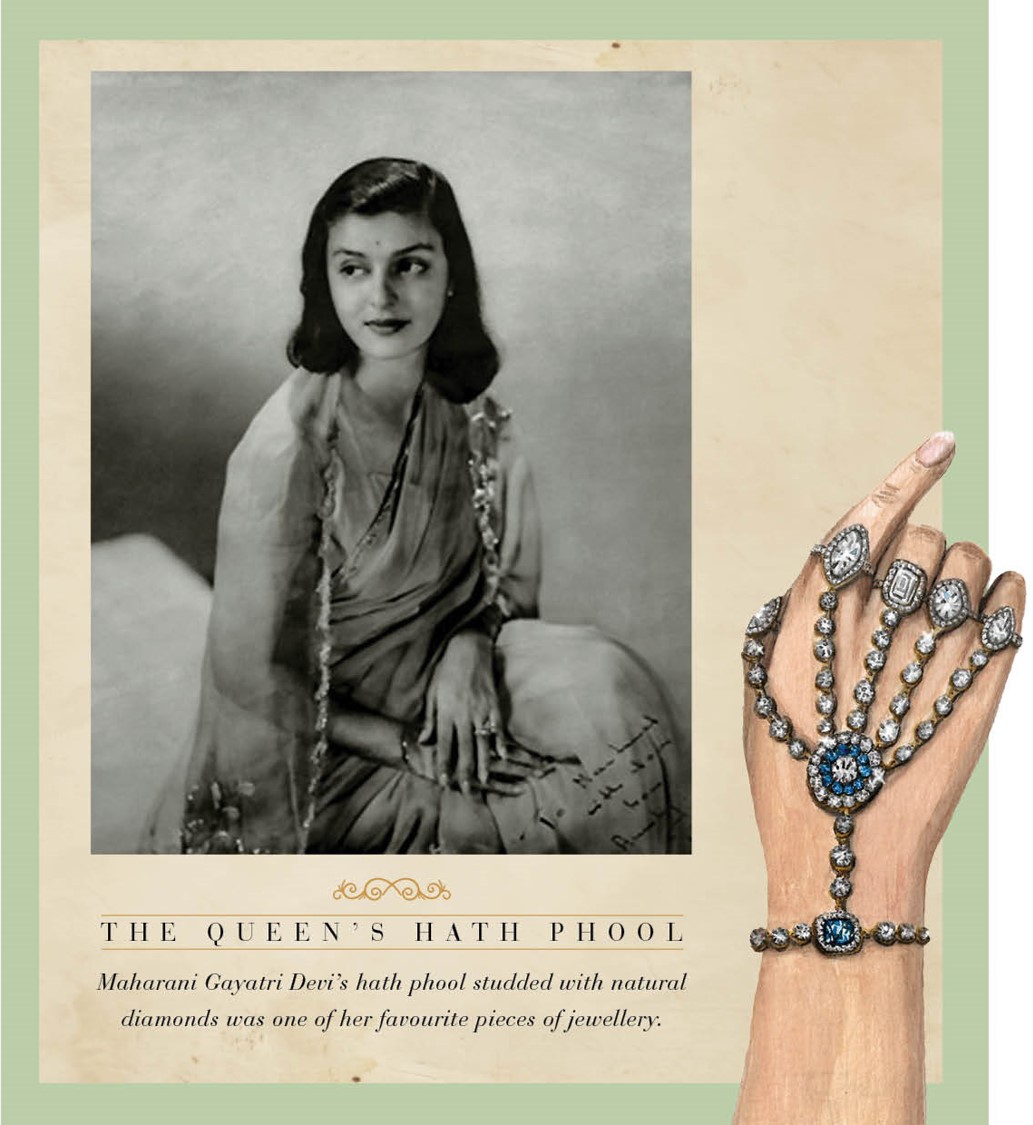

Frederick recalls a hath phool Maharani Gayatri Devi candidly spoke about in an interview with journalist Sathya Saran. The said hath phool design — a natural diamond-studded piece, with each finger sporting a diamond solitaire ring of a different shape, and a centrepiece intricately set with natural diamonds and sapphires — was one of the Maharani’s favourites. “She used to play bridge wearing it. Talk about jaw-dropping glamour!” adds Frederick.

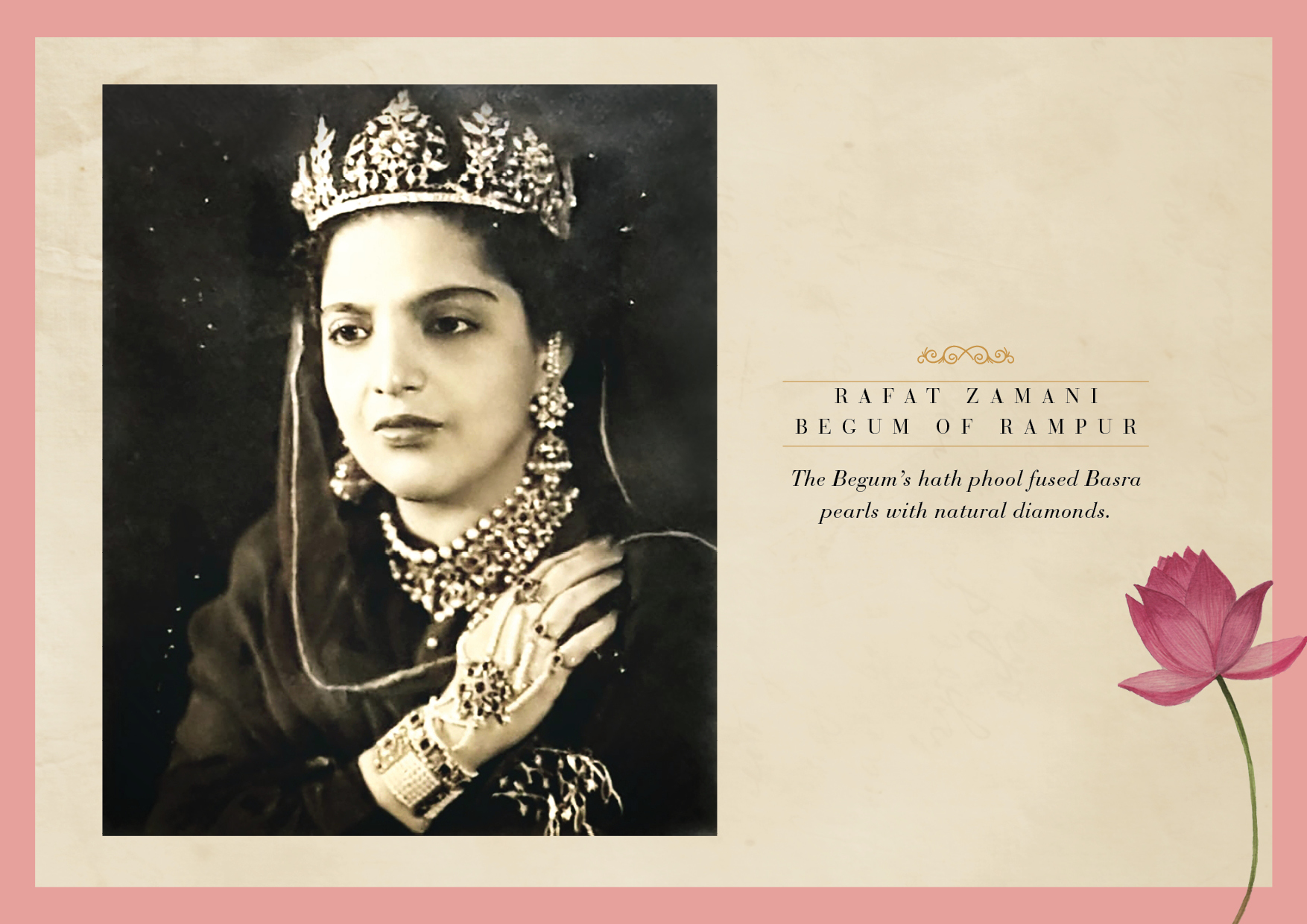

Hath phools enjoyed prominence in Nawabi culture too; a fact Nawab Syed Kazim Ali Khan, from the erstwhile royal family of Rampur as well as a former minister from Uttar Pradesh, attests to. The royal reveals that their collection of ancestral heirlooms features several hath phools. “Today’s contemporary hath phool designs tend to feature one ring and a single string. But our family’s designs are incredibly elaborate, covering each finger and the entire back of the palm. These were unique to our heritage, and unlike any other in the country,” says Khan, adding that they were custom-made for them by Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels who especially sent representatives to India for these orders. A standout hath phool design is one that belonged to Khan’s paternal grandmother Her Highness Rafat Zamani Begum of Rampur, the wife of the last Nawab of Rampur His Highness Nawab Syed Raza Ali Khan. “Rampur had the largest collection of basra pearls in British India, so that was the base of the hath phool,” he reminisces. “This was then set with natural diamonds like baguettes and round-cuts in a Victorian setting, accentuated by emeralds or rubies. We never used uncut diamonds as was the norm in other north-western states.”

Then and Now: The Hath Phool Today

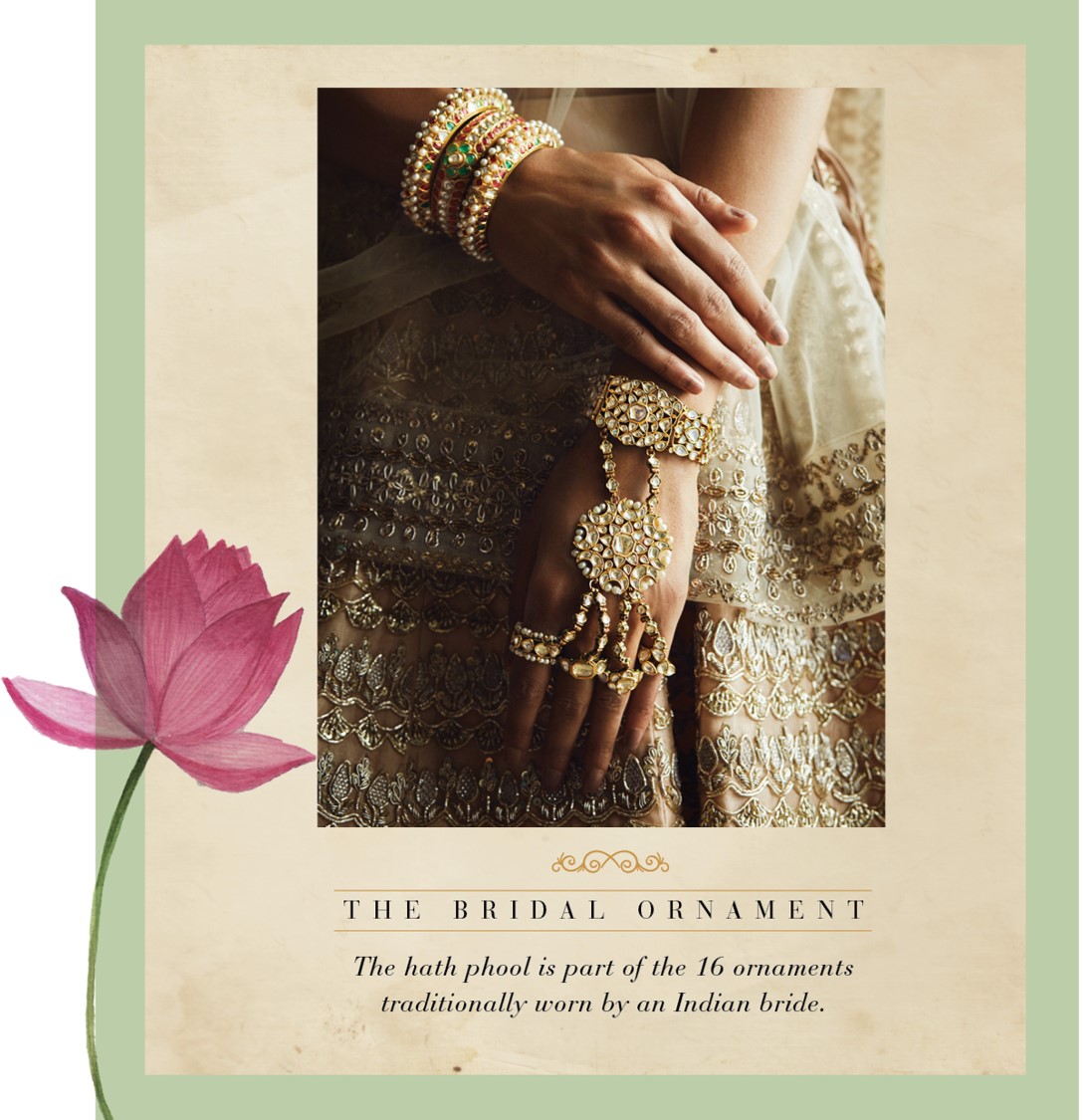

Today, the hath phool continues to be part of the solah shringar or 16 bridal ornaments that a Hindu bride typically adorns herself with on her wedding day — a custom that has been passed down for generations. Though the Van Gelder sisters note that decorating the hands dates to the Vedic period between 1500 to 500 BCE.

“The hands were considered vital limbs in performing prayers or rituals, and were stained with traditional designs — typically representations of the sun — on the palm. Wearing a hath phool is an extension of this concept, Fleur elaborates.”

Tarang Arora, creative director of Amrapali Jewels has access to vintage hath phools that are on display at the brand’s Amrapali Museum in Jaipur. Arora also works with the traditional Indian jewellery for his bridal and fine jewellery collections — handcrafting them using uncut diamonds, emeralds and rubies in floral motifs, especially the lotus, to stay true to its historical lineage.

The hath phool today, while respectful of its roots, has also undergone a makeover to marry its traditional past with a more present-day sensibility. As a result, jewellers now also create all-natural diamond contemporary versions of this beloved classic, displaying great creativity and craftsmanship. Arora adds that Amrapali too has been working on modern variations using rose-cut real diamonds and gemstones, apart from its famous polki designs. “The hath phool design has undergone a more lightweight makeover today, with many patrons opting for toned-down versions of the original.” With versatility being a paramount consideration in modern jewellery, detachable designs are now enjoying the spotlight. “So, we also work on customised diamond pieces, where the bracelet and rings can be detached and worn separately too,” adds Arora.

A study of the hath phool’s journey through time is a fascinating one — a testament to the eternal appeal of this homegrown jewel that continues to stay relevant even after several centuries.Frederick, who has witnessed its evolution to combine its Indian lineage with western traditions, says

“Wearing a hath phool with a natural diamond engagement ring has gained popularity in India. Not only does the hath phool provide a spectacular backdrop for the diamond ring, but it adds more substance to the overall look as well.”

What you have today is a complementing medley of something old and something new — much like the modern Indian jewellery connoisseur who likes her customary jewels spruced with abundant global flair. It’s a proud embrace of her roots with a subtle nod to her forward-thinking lifestyle — the best of both worlds, wrapped around her hand in one exquisite testament of unparalleled Indian artistry.