Feat of Engineering and Fancy

The word no can be a great motivator. A trained dancer, James de Givenchy, moved from Paris to New York to pursue a life on the stage, but an injury prevented him from pursuing his first passion. Born into a family steeped in creativity, his uncle is the famed fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy who famously dressed Audrey Hepburn at her most soignée. The pursuit of beauty and an artistic life led the young ex-pat to the rarified world of international auction houses— first Christie’s and then Sotheby’s. It was here that he embarked upon an intense education in the world of jewelry. After launching his own collection in 1996, he has met with rare success and acclaim; the jewelry designer for those who prefer that if you know, then you know. This sterling reputation notwithstanding, he still sometimes hears the word no when testing the boundaries of how rare jewels can be mounted. That’s when he knows, again, that he is onto something and has discovered another missed opportunity.

Only Natural Diamonds: What started you as a creator and as a designer?

James de Givenchy: Growing up, my uncle [Hubert de Givenchy] was a huge influence on me. I remember looking at every collection launched and taking [the critics] extremely personally. I left for America to be a dancer, [but] when that did not work out, due to a knee injury, I briefly considered going into choreography. My father had told me “You can do any art you want, but you’re going to have to make a living with it because I’m not taking care of you.” And rightly so. You have to be independent.

Ultimately I chose to go to FIT to study graphic design, which at that time sounded like a good idea, until I graduated and every graphic design company was merging. It was 1986… I found myself on a bench with my FIT portfolio alongside creative directors that were looking for the same job. My first full-time job in New York was as a developer at Photostats in the darkroom during the summer. Not a fun thing to do. Soon after, I was moved upstairs, and I finally had a table to draw on. My first project was designing diaper fasteners… And that is when I realized I wanted something bigger.

If you just focus on

the contemporary,

you will never

discover the

greatest times of

jewelry making

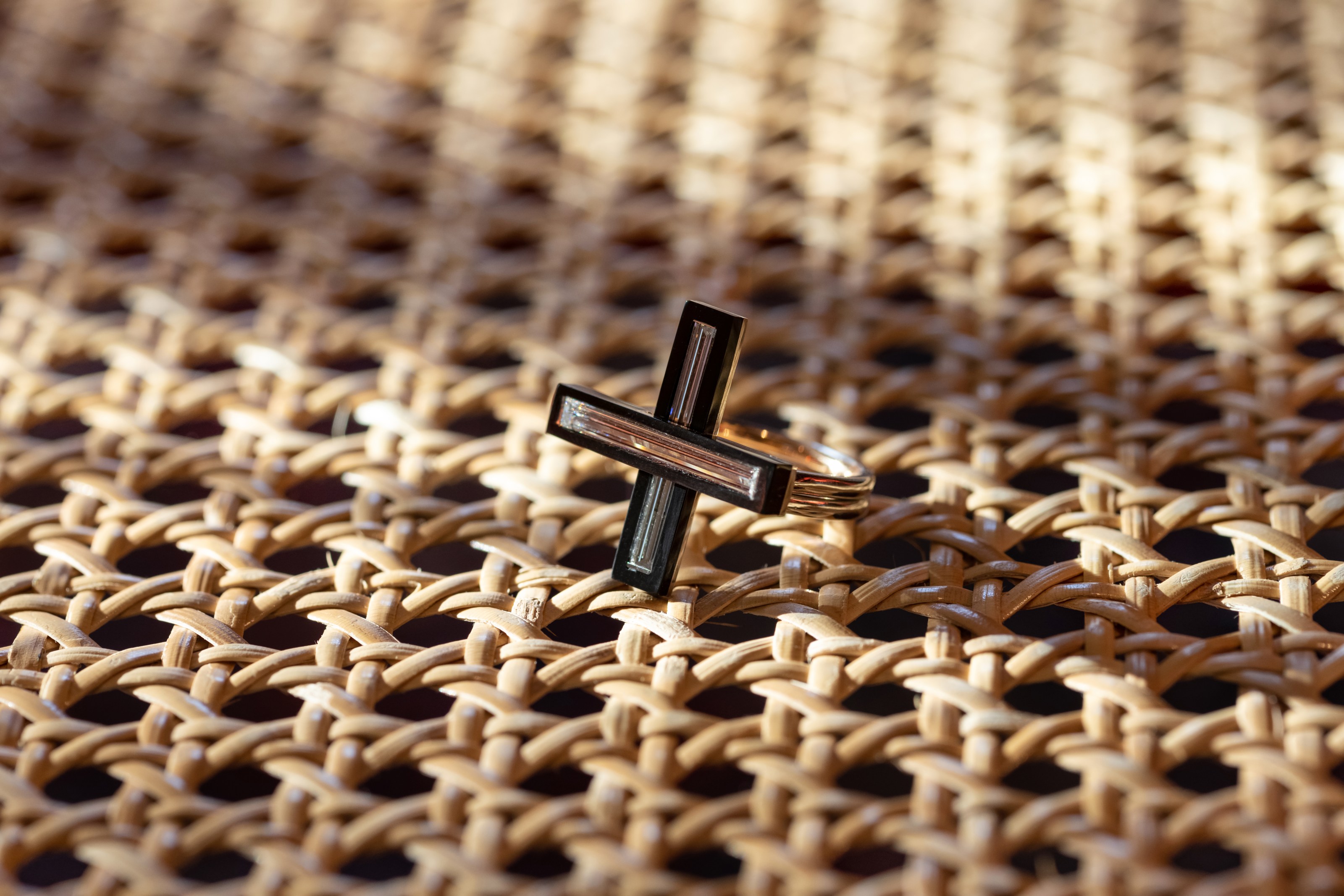

6.07-carat cabochon diamond with diamond pavé, ceramic, platinum, and 18K rose gold ring.

One thing led to another. I worked at the Givenchy store in New York City. At one point, my brother, who was an architect in Paris, asked me to do some work in New York. I enjoyed it until he asked me to come back to Paris and I said, “I’m not ready”.

So, I started looking for a job… Christie’s was offering positions, and I worked at the front counter for about six or seven months before the head of the jewelry department, Francois Curiel, asked me to come upstairs because of my accent. He said they needed someone with a French accent to answer the telephone.

I was doing my first viewing at Christie’s and my uncle came in. He was the most amazing man. He knew about everything. When he saw the large diamond at the end of the sale, he paused for a moment, and said, let me show you something. He went back to the first case, “show me the brooch” he said. It was the autumn leaf from Verdura. He went on to say, when you look at the big diamonds, they are beautiful. But this brooch shows what jewelry is about. It’s about putting it all together. It was this idea that triggered something in me. Christie’s offered me training. Honestly, there is no [better] place to train than an auction house for anyone who wants to become a jeweler. You’ll understand what it takes to make a piece. Because if you just focus on the contemporary, you will never discover the greatest times of jewelry making, like the ‘20s in France, for example. And you will see the technique and what is necessary to manufacture.

That is where I really fell in love with the industry and the challenge of creating and making jewelry, with stone and without. I went on to do [courses at GIA, the Gemological Institute of America], and I spent six years at Christie’s. Then I was hired by Verdura.

Eventually, I wanted to start my own business but, when I left Verdura with nothing and I thought, what am I going to do? A client then called out of the blue. She said, James, I have a drawing from Verdura, which I don’t care for. You always helped me at Christie’s and I’d love to see, now that you make jewelry, if you can do a drawing.

So, I made my first drawing and she loved it. That was the first piece I actually made as a special client piece. It was ’96. By 2000, I opened Taffin above the Givenchy store on Madison. It’s Carolina Herrera now. And I’ve just been trying to make new things every year, every day from that point on.

OND: It seems like many of your stories start with a stone. What prompts a new piece of jewelry? An idea or a stone or stones?

JDG: I often think it’s a stone. I always think of the [jewelry] safe as the kitchen fridge. When I go to a show, I’ll buy things that I don’t really know what to do with, and then it’s like opening the fridge before cooking something wonderful. I’ll pull things and I’ll play with them and move the stone around and then I’ll pair it with other stones. Sometimes, after a while, I either commit and know the direction or it goes back in the safe—or the fridge—for some time.

OND: How do you balance creating one-of-a-kind pieces while maintaining something that is instantly recognizable?

JDG: It doesn’t really cross my mind. Making new pieces is probably the hardest thing. I’m not looking to make new things specifically, I’m trying not to repeat myself. If I see myself getting lazy and falling in a direction that would be the easy one, I abandon it and I try something new. Sometimes it takes a while and an idea has to be played with.

This phrase, ‘thinking out of the box,’ is really important. It helps you freshen up the way you look at something. You might think something cannot be done or it shouldn’t be done —there is no such thing. It looks like Taffin simply because I had proportions in my mind and my soul. I do not try. Occasionally, I’ll be surprised by a piece that doesn’t look like Taffin.

OND: What do you think is the most important thing for you to be as a mentor? What is your responsibility or your opportunity?

JDG: It [is] wonderful to listen and to see what young people have in mind when it comes to their future and the future of jewelry. I realize that actually, we need more schools if we want to save the business. I think Europe has wonderful schools for that, but you can’t learn jewelry-making unless you work at a bench.

OND: But back to the fridge. What are the qualities that you look for in a diamond to decide if you want to use it?

JDG: Truly the first thing I see is the cut. I rarely look at color or clarity initially. It could be a small stone or a big stone but it really has to be pleasing to my sensibility and bring something. For me, a diamond that’s not clear or the right color for certain people could be the most beautiful stone in the world. It’s unique and it comes down to the way you set it.

OND: What draws you to certain colored stones over others?

JDG: It’s not so much the color, it’s the hue. You can mix any colors if the hue is right. Certain stones will give you something back and they could be so different and be a perfect marriage. It could be a citrine and a pink diamond if it works. And there is no reason why you should say, well that’s a cheap stone and that’s not. It’s irrelevant because it’s the beauty that they make together.

OND: And this is how you know that it’s Taffin. I think that is the through line. Are there any other pieces that you want to talk about?

JDG: I could talk about every one of them, but there was one beautiful pear-shaped ring. This is where I’ve been really interested in working now. With these shapes and these colors. I’m extremely attracted to this.

OND: This is very Miami.

JDG: It is but in a way for me-

OND: It’s Deco.

JDG: Yes, it’s Deco, but it has this modern, timeless thing. I love to mix the metal with the ceramic. Sometimes it’s in the middle, which is very difficult by the way because they are not the same hardness and will not polish the same way. Those are really tricky to make and make well because when you have those bands, any mistake you see on the thickness shows but then you are dealing, like my jewelers like to tell me, with a diamond that is not cut properly. So, it’s always the diamond’s fault. It’s always what you start with for me, these are some of the more fun pieces that I’m playing with at the moment, and you’ll see more of this. It’s not for everyone but I find I am very much into this right now.

OND: How long was this diamond in the fridge?

JDG: Diamonds don’t last in the fridge. It’s so funny. It’s like a steak.

But you want to say, no, these are the kind of things that don’t last but you never know. But I’m happy to keep it forever.

OND: I don’t think you’ll be keeping this forever.

JDG: You might have a piece for two years, three years and people come in and they go ‘That’s so pretty, why didn’t it go?’ And it’s like that because it hasn’t found its home. I think the [piece] has to find its owner. And it will. It’s not gonna sit here forever. And if it does, you know, my daughter will have it. But it just hasn’t found someone who is worthy of it, let’s put it this way.

OND: Who understands it?

JDG: Who understands it? Who is willing to just commit?

a diamond that’s not

clear or the right

color for certain

people could be the

most beautiful stone

in the world. It’s unique

and it comes down

to the way you set it.

8.21-carat fancy deep brown-ish-yellow round diamond, 18K rose gold & leather bracelet

OND: Can we talk a little bit more about the difficulty of setting in leather?

JDG: We had to really think of how. The setting itself is in the metal. The difficult thing was how do you hold it so that it’s really secure and you don’t have to worry. All I wanted to see was a diamond but ultimately you had to do something to hold it so we had to do the prongs. I wanted small prongs but then you realize that you have to do something that’s big enough to hold this in a sandwich and hard enough that it doesn’t move. It’s building the box underneath the diamond and then this finish that’s like a commercial watch but protects the diamond from getting dirty and from scratching. This is really something that I’m very excited about. As simple as it is, truly, I see men and women wearing this.

OND: Exactly. It’s not any one age or gender. I think you can be 90 years old on the Upper East Side and feel so cool or you can be 20.

JDG: And the excitement. Again, it’s not about making a hundred million of them but each one is going to be exciting be- cause each one is going to be about the stone. So, I’m looking forward to seeing what a single stone looks like on this. It could be rubber as well if you want to be a bit S&M. You can have a few stones. You could have a collection of diamonds on the bracelet.

OND: Is that next? Is that coming out of the fridge?

JDG: It’s going to come out of the fridge. Yeah. We have some big guys coming out of the fridge for this.

OND: Can we talk about the portrait cut heart on the leather cord?

JDG: So, this, the diamond here, is really interesting. That’s a stone that came from Christie’s at auction. It’s a beautiful antique Mughal cut diamond. It’s a portrait cut and after buying it, one of my dealers came in and he was bidding on it too. And I said, you know, it’s great, there’s a little nick and I’m wondering if I could polish it. He said, “Do not touch it! These stones were polished by hand. It’s 200 years old, maybe more, and you can see the softness of the polish on the stone.” They were using wood to polish the facets. It would take up to six weeks, I think, for one facet.

After looking at the stone, you can start seeing the softness of a polish, which is a high polish but not a very flat surface. So, if you were to polish it today, the whole thing would be extremely flat and you would lose the beauty of this diamond. Even after all these years, you never stop learning. What I wanted to do then, because it was Mughal, I [inscribed] love in Arabic and it’s on mother of pearl, which is put behind. I put it on rubber. Obviously, it could be worn on anything else.

Photography: Andrew Werner

Video Creative Director: Brian Anstey

Video Production: Arrow Media Productions