The Regent Diamond’s Thrilling Tale of Robbery, Royalty, and Revolution

Discover the riveting journey of the Regent Diamond: a story of intrigue and royalty.

Like many of history’s most famous gemstones, the Regent Diamond has a story rich with intrigue, treachery, and tumultuous drama. From the mines of 18th-century India to the glittering courts of Europe, its journey exemplifies the allure of natural diamonds and the great lengths people will go to possess such treasures.

The saga of the Regent Diamond begins in 1698, deep in the mines of Parityala, India. A worker, likely overwhelmed by the sheer size and beauty of the 410-carat stone he unearthed, decided to keep the gem for himself rather than surrender it to his superiors. With visions of freedom and wealth, he hid the diamond in a leg wound, which he suffered while fleeing the 1687 siege of Golconda. It was a desperate and clever move that allowed him to smuggle the stone past the watchful eyes of the mine’s overseers. His cunning plan worked, and the worker set off for Madras, hoping to sell the stolen diamond in one of India’s bustling secondary markets.

However, his dreams of freedom quickly turned into a nightmare. The worker made the fatal mistake of trusting an English sea captain to ferry him to safety by making a deal with him and offering him 50% of all profits on the diamond sale. The captain, driven by greed, forcibly took the diamond from the worker and tossed the poor man overboard in a cruel twist of fate. Arriving in Madras, the captain sold the gem to the well-known diamond merchant Jaychand for £1,000. But karma soon caught up with the captain; after squandering his ill-gotten gains, he reportedly hung himself, perhaps haunted by his actions.

Jaychand, too, faced difficulties in selling the diamond, which was now known to be stolen property. The word eventually reached the Governor of Madras, Thomas Pitt, who was keen to acquire the gem. Pitt, a shrewd negotiator, spent months wearing down Jaychand, eventually purchasing the diamond for a mere £20,000—a fraction of its initial asking price of £85,000. While financially advantageous, the deal nearly ruined Pitt’s reputation as whispers of the stone’s dubious origins spread. Nevertheless, Pitt sent the diamond to London, concealed in his son’s shoe heel, to be cut and polished.

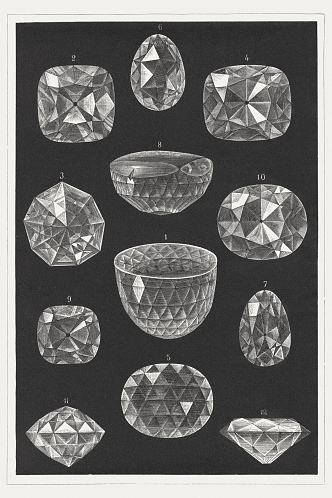

The transformation of the stone was nothing short of miraculous. Diamond-cutting artist Joseph Cope spent two years carefully transforming the rough 410-carat diamond into a 140.5-carat brilliant cushion-cut gem. The process involved intricate cutting and polishing techniques to enhance the rough diamond’s brilliance and beauty. Rumors suggest several smaller diamonds cut from the same rough were later sold to Peter the Great of Russia. At the same time, the main stone, now known as the Pitt Diamond, was offered to royalty across Europe, including Louis XIV, who had famously purchased what became the Hope Diamond in 1699. None of the monarchs who were offered the extraordinary diamond chose to buy it until 1717, when Philippe II, acting as Regent of France, acquired it for the crown jewels. Its sale price of £135,000 was a nice profit for Pitt, who had bought the rough for a mere £20,00 0a few years earlier. Following the sale, the Pitt Diamond became known as “Le Régent” and a symbol of French royalty.

The Regent Diamond quickly became a prized possession of the French monarchy. They prominently displayed the cushion-cut diamond during key formal occasions, including state functions, royal weddings, and successive coronations. It graced the crowns of multiple French monarchs, beginning with Louis XV in 1722 and later with Louis XVI in 1775. The diamond even adorned a hat worn by Marie Antoinette. By 1791, the Regent Diamond’s value had soared more than four times its original purchase price, making it the most valuable and symbolic jewel in France, a testament to the grandeur of French royalty.

As the French Revolution unfolded, “Le Régent” was embroiled in the chaos alongside the rest of the French crown jewels. The revolution, which began in 1789 and lasted until 1799, marked a period of radical social and political change in France. Someone stole the diamond during this turbulent period, but luck favored it when someone discovered it hidden in the roof timbers of an abandoned attic in Paris. The French Ministry of Finance swiftly took control of the gem, recognizing its value and using it practically as collateral for loans.

Between 1797 and 1801, the Regent Diamond acted as a “security deposit” to finance the military expenses of the new Directoire Government. Investors from cities like Berlin and Amsterdam held the diamond as security against France’s national expenditures, symbolizing France’s turbulent changes. In 1801, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte finally reclaimed the diamond for France.

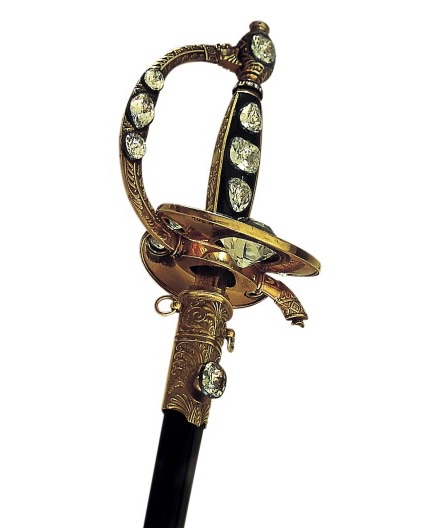

Napoleon, never one to shy away from opulence, first had the Regent Diamond set into the sheath of his sword belt. He later commissioned its placement into the pommel hilt of a ceremonial sword crafted by the renowned jewelers and goldsmiths Odiot, Boutet, and Marie-Etienne Nitot, the official jeweler to the Emperor and founder of the House of Chaumet. In 1812, the diamond appeared in a well-known painting of Napoleon, prominently displayed atop his ceremonial sword.

During her exile, Napoleon’s Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria removed the diamond from its mounting and took it to Austria. However, her father insisted she return the gem to Charles X of France, who incorporated it into his crown. “Le Régent” continued its illustrious journey, adorning the crowns of successive French monarchs, including Louis XVIII, Charles X, and Napoleon III.

When Napoleon III came to power, he allowed his wife, Empress Eugénie, to borrow the Regent Diamond. She technically wasn’t permitted to wear royal jewels because of her status as the consort rather than the reigning monarch. In many royal traditions, the official crown jewels are reserved for the reigning king or queen, and consorts may be restricted in their use of these symbols of sovereignty. In order to get around the rule, Eugénie ingeniously integrated the diamond into her hair, placing it in a Greek-style diadem that still carries her name today. This period marked a new chapter in the diamond’s history, as it was used in a more personal and innovative way, reflecting the changing times and the evolving role of the French monarchy.

In 1887, the young French Republic decided to auction off much of the country’s crown jewels. However, the diadem containing the Regent Diamond was spared from the auction, and instead, a home was found on display at the Louvre Museum, where it is still on view. The only time this display was interrupted was during World War II when the French government, fearing that the German army might plunder the diamond and other priceless treasures, secretly moved the Regent Diamond to the countryside town of Chambord for safekeeping until the war’s end.

The Regent Diamond’s journey from the mines of India to the halls of the Louvre is a tale filled with adventure, betrayal, and the relentless pursuit of beauty. Its story reminds us of the power of natural diamonds as symbols of wealth and pieces of history that have been touched by the hands—and fates—of many.